Earlier this month, while I was waiting to undergo minor surgery, the hospital professionals would introduce themselves to me by first name. This practice provided emotional comfort for anticipating inevitable pain, as if to say “I am the name attached to the fingers that will fish around inside of you,”—a private acknowledgement of what was to come, from one body to another.

Though I swiftly forgot the names, the introductions were sufficient enough that in my first half-lucid moments following general anesthesia, lightly gowned and heavily woozy, I exclaimed: “But you were there, and you, and you,” before being calmly shushed by the attending nurse.

A view of Lyse Lemieux’s “FULL FRONTAL” installation in the windows of the Contemporary Art Gallery in Vancouver. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Robert Keziere.

A view of Lyse Lemieux’s “FULL FRONTAL” installation in the windows of the Contemporary Art Gallery in Vancouver. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Robert Keziere.

Lyse Lemieux’s “FULL FRONTAL” consists of printed vinyl coverings for the windows of the Contemporary Art Gallery and for the nearby glass entrance to the underground rapid transit stop, Yaletown-Roundhouse Station. The overbearing black and white textures and ellipses alter the architectural perceptions of both sites, creating momentary confusion between applied pattern and structural pillar or girder—like building-appropriate versions of facial anti-surveillance make-up. A closer examination of the imagery reveals portions to be high-resolution scans of woven fabric, with enlarged hairs included among its fibres for scale.

Personified concrete, glass and steel is not so far from Lemieux’s established wheelhouse. The artist often uses textiles, paper, ink and felt to create bodily references in her practice that bounces between figuration and abstraction—a pleated trapezoid becomes as much the thighs under a skirted uniform as the apparel itself. The term “full-frontal” implies nudity, instructing us to read the printed sticker coating in this exhibition as epidermis, rather than mere clothing.

Vinyl coverings have become materially ubiquitous—a practical, impermanent manner for advertisers to add quick visual dynamism. By drawing parallels to the body, Lemieux’s installation may use this ubiquity and impermanence to its advantage—can the viewer foresee the inevitable peeling of skin come exhibition close?

A view of Lyse Lemieux’s “FULL FRONTAL” installation at Yale-Roundhouse Station in Vancouver. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Robert Keziere.

A view of Lyse Lemieux’s “FULL FRONTAL” installation at Yale-Roundhouse Station in Vancouver. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Robert Keziere.

Bodily contexts continue elsewhere in the city. Spare Room, a small exhibition space nestled among the second floor artist studios at 222 East Georgia Street hosts “Mucking around at the beginning and the end” by Julian Hou and Sylvain Sailly. In Hou’s Memory Tamer (2017), a male mannequin sits centre gallery wearing a striped tunic and bonnet that match the bright colours of Spare Room’s flooring.

With his scuff marks and outmoded scowl, the figure is not an eye-catching shop display, but a bygone castoff. He arouses pity in infantile attire—something between a surgical smock and 1920s swimwear. Seated in a tangle of magnetic tape amidst a structure of precariously arranged dowels, Hank (so named in the gallery handout) evokes visions of a passed out partygoer, stacked upon by pals with nearby objects.

A view of Julian Hou and Sylvain Sailly’s exhibition “Mucking around at the beginning and the end” at Spare Room in Vancouver. Photo: Dennis Ha.

A view of Julian Hou and Sylvain Sailly’s exhibition “Mucking around at the beginning and the end” at Spare Room in Vancouver. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Helplessness connects the works. Hou’s Stupid sun (2017), is a single channel video with a droning soundtrack, over which alternating voices recite a script of declaratives, calls and responses. The imagery is twitchy and out of focus, hovering at the edge of the camera’s vision—too bright, too close or too dark. We see the sun behind the trees and clouds, water droplets on a clear substrate, and a grainy, dimly glowing orb, among other hazy views.

A short, slowed clip of Willem Defoe as David Caravaggio appears, from the 1996 war drama The English Patient. If you’ve seen the film, you’ll remember the scene where Caravaggio, a Canadian Intelligence Corps operative, has his thumbs cut off during interrogation. Like Hank, another captive body tormented. “What are you doing to me?” a voice asks later in Hou’s video. “I’m healing your sincerity,” a second answers.

A closer of view of Julian Hou’s Memory Tamer at Spare Room in Vancouver. Photo: Dennis Ha.

A closer of view of Julian Hou’s Memory Tamer at Spare Room in Vancouver. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Sylvain Sailly’s Shelter is an animation and accompanying comic produced using SketchUp, a 3D modelling computer program. Isolated on a beige and featureless ground, a rigid rectangular plane perforated by circles leans on, or is pinned in place by two vertical rods. A light source overhead casts a Swiss Cheese-like shadow, while a cursor selects and deletes the circular voids, undoing previously drawn elements.

At the Cinematheque, as part of an off-site closing reception for the exhibition, a musical performance by Julian Hou and Ellis Sam spills into the theatre from the lobby while Sailly presents a live SketchUp demonstration. Working from the projection booth, an unseen performer connects wires between five depicted utility poles. The cursor moves in short segments, its trackpad disproportionate to the excessively large movie screen monitor.

“Mucking around” implies an unpurposeful effort, a waste of time or half-hearted attempt that lacks the right tools or know-how. Perhaps these works, like Hou’s periwinkle and aqua-rapids tunic, are site-specific responses, in this case to the extravagance of a gallery that declares itself “spare” in a city where affordable rooms are scarce.

Viewers take in collaborative works by Emily Neufeld and Pegah Tabassinejad during the opening for “Migrations” at WNDW. WNDW is an itinerant art space in Vancouver coordinated by Lexie Owen.

Viewers take in collaborative works by Emily Neufeld and Pegah Tabassinejad during the opening for “Migrations” at WNDW. WNDW is an itinerant art space in Vancouver coordinated by Lexie Owen.

Is it scarcity of art spaces that leads to initiatives like WNDW, a roving project that occupies residential windows? The current exhibition “Migrations” features collaborative works by Vancouver-based Emily Neufeld and Tehran-based Pegah Tabassinejad.

From the living room toward the lawn just off Arbutus Street at 14th Avenue, a relatively modest screen presents a single-channel video of footage alternating between domestic spaces. A time-lapse captures sunlight patterns shifting across a sitting room, spilling onto the floor where a tabby cat comes to bask. Matching curtains imply we’ve been given special access into the exhibiting home.

A film still from Emily Neufeld and Pegah Tabassinejad’s collaborative project “Migrations” at WNDW in Vancouver.

A film still from Emily Neufeld and Pegah Tabassinejad’s collaborative project “Migrations” at WNDW in Vancouver.

Creating a dialogue between here and there, a contrasting segment shows surveillance footage of somewhere else—we see a railed balcony, a polished floor, a living room and an unmade bed below a curtained window. An unease is articulated through a sophisticated language of security, with split-screen views labelled as Camera 1 through 4, and a flashing red icon that appears when movement is detected.

A live monitor seen in the background of one angle, however, indicates the surveilled resident is also the surveillant. She appears at various moments, as a twirl of draped fabric, or from the ankle down, later grabbing car keys off a desk before heading out the door.

A view of WNDW’s signage in Vancouver, which mimics real-estate conventions. WNDW is an itinerant art space coordinated by Lexie Owen.

A view of WNDW’s signage in Vancouver, which mimics real-estate conventions. WNDW is an itinerant art space coordinated by Lexie Owen.

A second collaborative work appropriates real estate lawn signage and flyers as a means to convey information gathered by the artists, in both Tehran and Vancouver, about their neighbours’ homes and ancestors. The flyers are confusing, mixing details, about ten or so houses, with real estate signifiers, such as logos, QR codes and headshots.

A statement on the WNDW website reads: “The project aims to bring contemporary art out of self-selecting high culture areas placing it directly into the quotidian life of the residential street.” This is a fine gesture, but what does the art do on the street once it’s there? Without a little more drama, of venue or scale, “Migrations” comes close to blending in.

Back to the white cube. Or Gallery describes Kapwani Kiwanga’s recent “Flowers for Africa” as “a conceptual project that questions the material from which history is pictured and remembered.” Delving into photographic archives related to decolonization, the artist identifies celebratory flower arrangements from images of ceremonial events connected to African independence. Working with local florists, she recreates the varied arrangements—nine that I saw at Or, ranging from an ornate wall hanging to a modest boutonnière—before placing them in the gallery. Displayed on stark plinths of differing sizes, the fresh flowers are left to wilt for the duration of the exhibition, drawing a parallel to fading memory.

The project turns the gallery experience into a ceremony itself. Few things are as universally appreciated as fresh-cut flowers. We’re well familiar with their lush textures, colours and smells, we know how to care for them, and how much to pay for them, while every floral shop displays impressive bouquets. I can imagine that some potential viewers missed this exhibition, satisfied by its description alone.

Present at the opening reception, I made a point, like many others, of returning to the Or on the last day of the show, hypothesizing a scatter of organic material and a pungent, mulchy scent. As it turns out, a gallery is an ideal environment in which for flowers to dry. The arrangements were uncannily intact and sweetly aromatic, shedding minimal petals and retaining vibrant hues.

I soon found myself swiping through my phone for snapshots of the room five weeks prior—the images carrying with them the memory of reverberating crowd sounds. Standing among Kiwanga’s works, I contemplated whether or not it was possible for flowers to be markedly less audible than photographs.

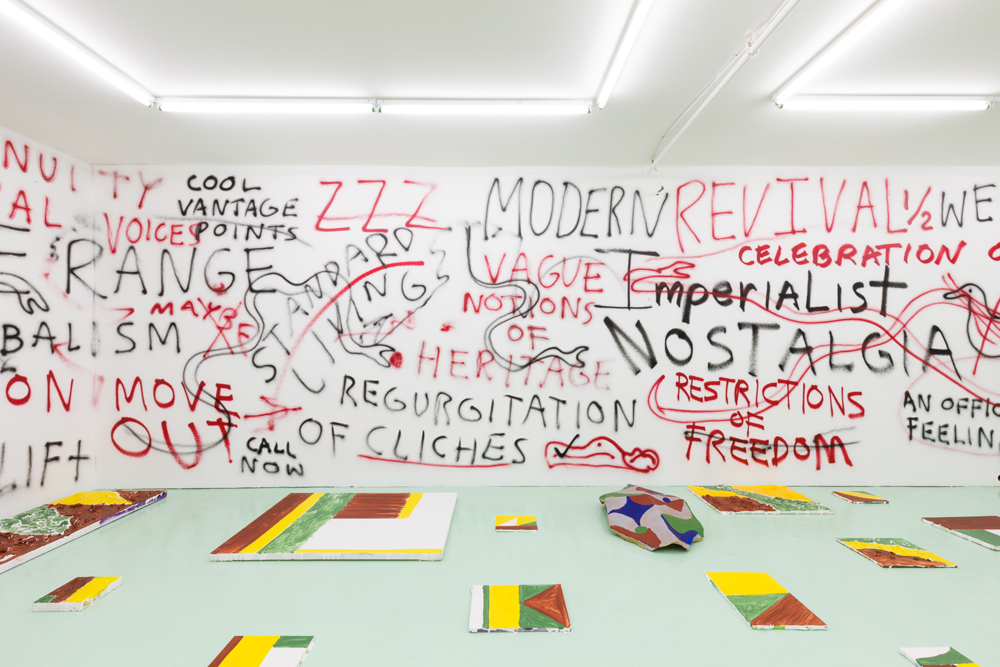

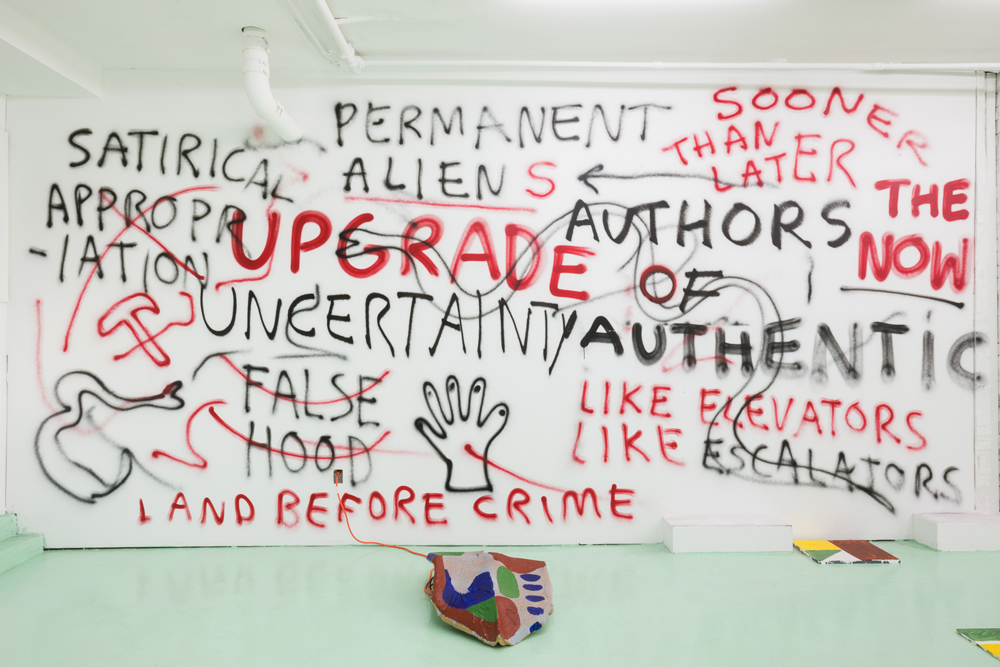

A view of Patrick Cruz’s exhibition “Quarantine Of Difference” at Wil Aballe Art Projects in Vancouver. Photo: Dennis Ha.

A view of Patrick Cruz’s exhibition “Quarantine Of Difference” at Wil Aballe Art Projects in Vancouver. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Patrick Cruz’s “Quarantine of Difference” at Wil Aballe Art Projects, compared to the artist’s other recent solo exhibitions, demonstrates his version of restraint. The white walls of the gallery are covered in red and black graffiti, with words that convey political struggle next to phrases that seem more appropriate as branding slogans.

Together they’re confounding—in ALL CAPS but not quite angry, and not soothing either. Self-negating, they perform best as a chaotic texture, contrasting with the visually more subdued elements in the room.

A view of Patrick Cruz’s exhibition “Quarantine Of Difference” at Wil Aballe Art Projects in Vancouver. Photo: Dennis Ha.

A view of Patrick Cruz’s exhibition “Quarantine Of Difference” at Wil Aballe Art Projects in Vancouver. Photo: Dennis Ha.

Twenty-eight acrylic paintings of varying sizes lie on the gallery floor, which has been freshly painted a glossy seafoam green. Were it not for the crowd of people at the opening, the channels between works would feel spacious coming from Cruz, whose complexly patterned installations often cover the entirety of exhibition spaces. These new paintings, tri-colour and loosely geometric, were made on re-primed older ones. Fittingly, a word on the muddled wall reads “cannibalism.”

A veiled violence extends to other works. Containments (2017) consists of three painted plaster sculptures surfaced with faux stone. A paper guide describes them as borrowing from mask and turtle shell forms, with the shells serving as metaphors for empty houses. A turtle’s shell, however, is part of its body—framing it as a home, especially an empty one, also implies a death.

On display upstairs from WAAP, at Fazakas Gallery, are masks from the Undersea Kingdom series (2016–2017) by the late Beau Dick—the celebrated carver, artist, activist and hereditary chief passed away earlier this year. The works were shown this Summer as part of Documenta 14, in Athens and then in Kassel, where I was also privileged to have seen them. On the first morning of my two-day Documenta ticket, I had been moving venue to venue without the daybook or map for guidance, and had arrived at the series unprepared for its arresting affect.

Whether due to their cultural importance beyond a contemporary art context, to their symbolic materiality, to their innovative forms, or to some permeating unseen energy, their impact compared to other Documenta 14 works was unparalleled. I felt humbled in their presence—and still do, seeing them here. I want to ask them where they’ve been, and where they’ll go, half expecting the answer to involve some passage through another realm.

Lucien Durey is an artist based in Vancouver. His performative works engage with collections, found objects and ephemera.

This post has been updated from the original. The original post was inadvertently created using a non-final draft. Canadian Art accepts full responsibility for this mixup and apologizes to author and readers for any confusion.

A view of Patrick Cruz’s exhibition “Quarantine Of Difference” at Wil Aballe Art Projects in Vancouver. Photo: Dennis Ha.

A view of Patrick Cruz’s exhibition “Quarantine Of Difference” at Wil Aballe Art Projects in Vancouver. Photo: Dennis Ha.