A passage in Judy Radul’s most recent artist book recalls a telling feedback loop. When the artist would tell friends she was making a book about television, they would often respond with anecdotes or suggestions about stories to include, or things to look at. Many such recollections appear in the book’s “ORAL HISTORY” chapter. The quotations are presented in uninflected sans serif font and sit in white text boxes, digitally collaged onto photographs of discarded televisions, and technical diagrams and satellite dishes. Overall the book mimics a layered consciousness, in which elegant human recall is joined with its collaborators, in the form of bulky and entropic memory machines. A project about television might seem as newfangled as a cathode-ray screen, but the charm of Radul’s montage technique is the uncanniness with which it inspirits the familiar bookish appearance.

Much legwork is done by its idiosyncratic design scheme. In certain sections, the book seems a wry structuralist incantation of some outmoded textbook. While text blocks echo manuals for learning, the subjectivity and whimsy of their content elegantly perverts authority and comprehension. In turn, the table of contents flits between a conventional—if cryptic—list of topics and quirky fragments of poetry. The chapter heading “CRAIG” suggests a narrative protagonist, but in fact it precedes many photo spreads reproducing Craigslist ads for out-of-work and out-of-style television sets. Still, CRAIG haunts the ads, underling the machine’s pathetic charisma.

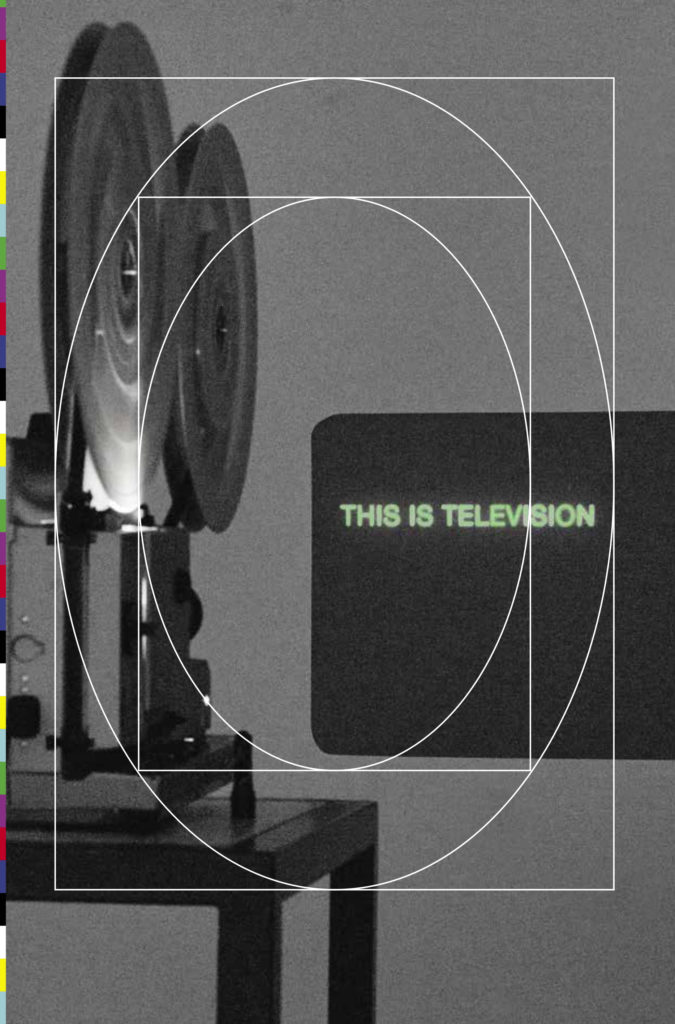

This is Radul’s sharp way of reflecting rather than analyzing the fetish character of her commodity subject—also a technology, a form of memory and a conflicted vehicle of ideology. Three commissioned essays (titled “This,” “Is” and “Television”) provide their own kind of illumination, while also capitulating to a conventionally academic mode of critique—unnecessarily, given Radul’s weird but powerful wielding of the codex form. More novel, for their bundling of nostalgic fetishism with hobbyist anthropology, are pages reproducing the covers and colophons of the many books that theorized and grappled with nascent television technology.

In its astute playfulness, Radul’s book becomes a mischievous shadow self to its intoxicating and vexing technological subject. Her own writing amplifies this quality. The essay “Marquee Moon”—accompanied by fragmentary images of the 2013 exhibition at Berlin’s DAAD gallery, from which the book developed—moves this way and that, weaving an explanation of the historical relationship between watching television and moon-gazing.

Judy Radul, This Is Television (book cover). Courtesy Sternberg Press.

Judy Radul, This Is Television (book cover). Courtesy Sternberg Press.