A quote by Guillermo Gómez-Peña opens the exhibition “Frontera: Views of the U.S.-Mexico Border” at the National Gallery of Canada:

“Travelling, both geographically and culturally, becomes an intrinsic part of the artistic process, particularly for those of us who see ourselves as migrants or border crossers.”

This statement sets the tone for the photographic perspective inside the exhibition, which offers the view of artists in constant movement, artists who capture their particular interpretations of the geopolitical, economic and social issues surrounding the border between Mexico and the United States.

“Frontera” primarily presents aerial representations of landscapes—that is, traces of migration, with only two instances of actual human representation.

A bird’s eye view of history unfolds, too, in a timeline on the wall that provides a chronological account of events dating from the Mexican-American War in 1846 onwards, helping viewers understand the inevitable present-day political outcomes. By the late 1840s, Mexico had lost over one-third of its original territory and the U.S. had established the Rio Grande as its border.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the timeline suggests, an economic impetus developed for the declaration of war on drugs. The final didactic note, on the 1980s and 1990s, turns visitors’ attention back to the gaze of artists who, whether in the States or in Mexico, became cultural political agents addressing the realities of living along the border.

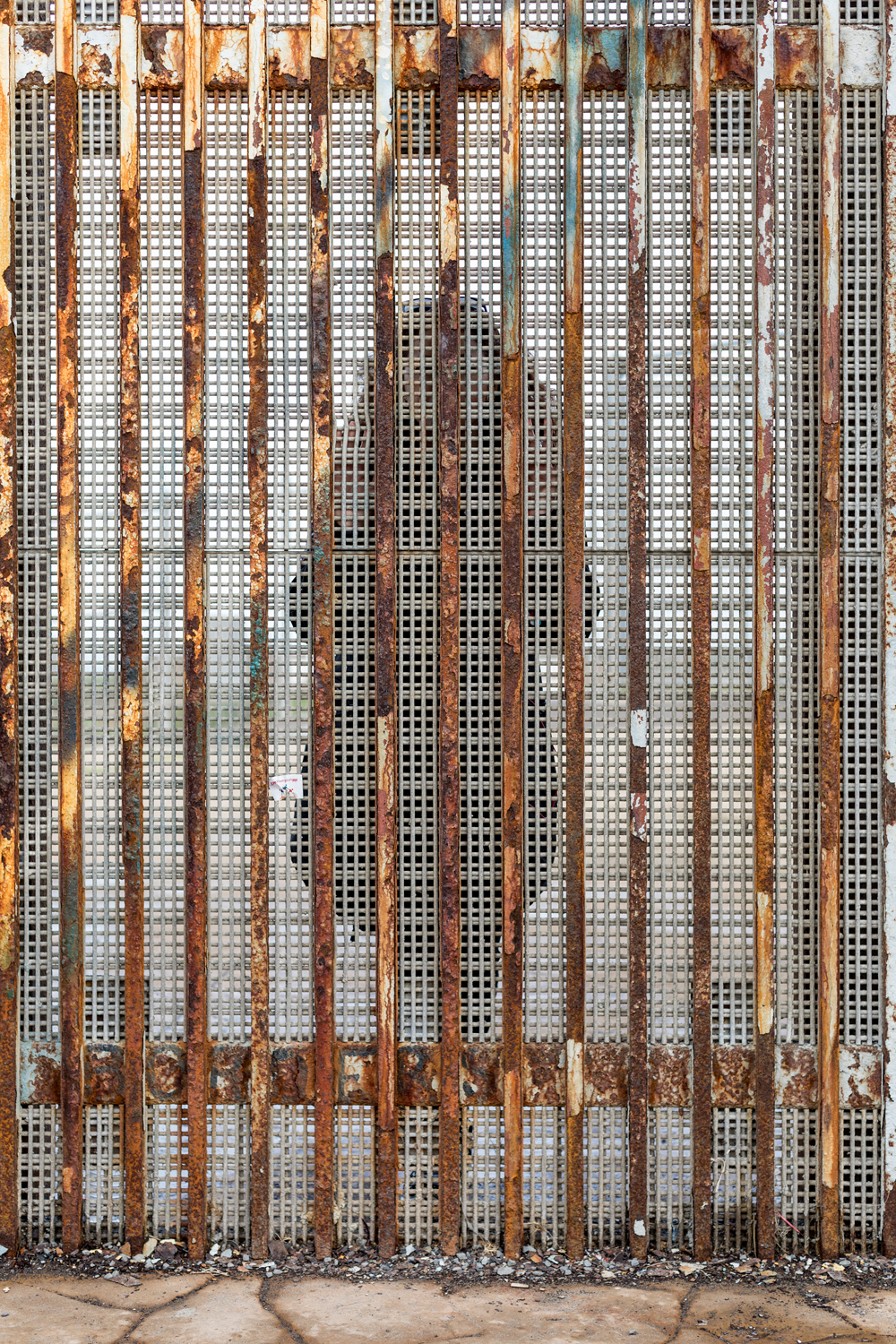

Alejandro Cartagena, Daughter on the USA-Mexico Border Wall, Border Field State Park, California, 2017. Digital print. Collection of the artist. Photo: Alejandro Cartagena.

Alejandro Cartagena, Daughter on the USA-Mexico Border Wall, Border Field State Park, California, 2017. Digital print. Collection of the artist. Photo: Alejandro Cartagena.

Monterrey-based Alejandro Cartagena, who in 2015 exhibited his well-known series Carpoolers (2011–12) during Contact Photography Festival in Toronto, uses the visible frontier to accentuate the divide between families who live on either side of the border.

Without Walls is a series Cartagena shot along the Tijuana–San Diego border in 2017; one of the images of the series, Daughter on the USA-Mexico Border Wall, Border Field State Park, California, covers an entire gallery wall, offering a perspective of how the relationship changes between parent and child once the border is crossed.

In this image, Daughter, one can only see a shadowed silhouette of a girl behind a rusted metal grid; touch is impossible, for fingers can barely squeeze through. The eyes of the girl are barely distinguishable through the gate. The physical connection between child and parent ceases, no longer visible—at least to onlookers.

Pablo López Luz, on the other hand, zooms out high above and captures the demarcation line that divides both countries. This series, shot in 2013 and also entitled Frontera, consists of photographs that reflect a harsh, uneven terrain. This aerial view of the landscape follows some 3,000 kilometres of border, approximately 1,000 of which is walled.

Pablo Lopez Luz, Tijuana – San Diego County III, Frontera Mexico – USA, 2014. Inkjet print, 61 x 73 cm. Collection of the artist. Photo: Pablo Lopez Luz.

Pablo Lopez Luz, Tijuana – San Diego County III, Frontera Mexico – USA, 2014. Inkjet print, 61 x 73 cm. Collection of the artist. Photo: Pablo Lopez Luz.

Canadian artist Geoffrey James and American-Canadian artist Mark Ruwedel, both largely foreigners to this particular border landscape, attempt to mark human presence by documenting its absence. Both offer impressive bodies of work in gelatin silver prints, recording a landscape that is often forgotten or hidden, and that is uncovered and presented with only traces of migrant activity.

Ruwedel, in his images from the series Crossing (2001–10), looks down and documents crushed plastic water bottles, abandoned garments and lost passports found under trees and bushes, materials often blending in with the existing terrain. We know we are close to the border without having to see photographs of the border itself.

Geoffrey James’s Running Fence (1997) documents the titular fence from both sides of the border. The artist here moves freely back and forth between two sides, a perspective of uncensored privilege.

In his video Coyote Flies (2014), Swiss artist Adrien Missika alludes to the cunning smugglers who, for hefty ransoms, help migrants cross the border to the United States. In this case, Missika uses a drone that flies freely over the border without obstacles, without barriers, without scrutiny and without security impediments. Our consequent view as spectators is one of unease; we witness the exact location coordinates we “fly” over accompanied by a background soundtrack composed by Victor Tricard.

Adrien Missika, We Didn’t Cross the Border, The Border Crossed Us, 2014. Photograph, set of 16, 49 x 39 x 3 cm. Courtesy Galerie Bugada & Cargnel, Paris. Photo: Adrien Missika.

Adrien Missika, We Didn’t Cross the Border, The Border Crossed Us, 2014. Photograph, set of 16, 49 x 39 x 3 cm. Courtesy Galerie Bugada & Cargnel, Paris. Photo: Adrien Missika.

States Border: The Mexico-United States Border (2015) by Los Angeles–based artist Daniel Schwarz is a sculptural photographic rendering of disruptions and social tensions along the US-Mexico border. Comprised of Google Maps satellite images, the piece is an accordion-style book displayed as two long, mountainous surfaces; each book, unfolded, is 25.4 metres long, and viewing it, one can see from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. Ironically, much like mainstream media coverage of the border itself, this accordion book will simply be folded, stored and largely ignored once the exhibition is completed. It is not until they hear about the border in the news again, or see an exhibition discussing its issues, that many people acknowledge this boundary line and its politics.

American photojournalist Kirsten Luce attempts to denounce the violence of US border patrols with her larger-than-life images. Each image mimics the view as seen from a surveillance helicopter, a view of migrants trying to flee from border patrols that have become more violent than ever before. The olive green Rio Grande covers the gallery wall in As Above, So Below (2014–15), a body of work in which the artist documents drug trafficking and human smuggling into the United Sates through the Rio Grande, the most controlled border in the world.

Right before the exit, then, the final perspective of the border, through Luce’s work, is of human crisis and of immeasurable consequence. The exhibition’s last image is of a man crossing the river with water up to to his chest, carrying his clothes in a plastic black bag, and it summons an overwhelming sense of despair.

Kirsten Luce, A solitary smuggler calmly swims back to Mexico with his clothing in a garbage bag. Once smugglers or migrants enter the Rio Grande river, they are out of the jurisdiction of the Border Patrol and savvy smugglers take advantage of this. From the series As Above, So Below, 2014–15. Digital print. Collection of the artist Photo: Kirsten Luce.

Kirsten Luce, A solitary smuggler calmly swims back to Mexico with his clothing in a garbage bag. Once smugglers or migrants enter the Rio Grande river, they are out of the jurisdiction of the Border Patrol and savvy smugglers take advantage of this. From the series As Above, So Below, 2014–15. Digital print. Collection of the artist Photo: Kirsten Luce.

And yet, navigating the exhibition, it is almost impossible not to question the repetitive perspectives on offer, the distance between subject and narrative, and the continued pictorial absence of some of the millions of people affected by the Mexico-US border.

Because of this distanced approach, “Frontera” marks a division between “they” and “we,” purposely choosing to make this distinction as artists document a space of conflict. We cannot forget that it is the remote, privileged perspective of the artist that can often offer a black-and-white viewpoint of the issues at stake. And although all of the artists’ series here mark crucial evidence of a devastating contemporary phenomenon, the overall exhibition does not capture the variances, complexities and multiple experiences that such a relevant theme has the potential to contain.

“Frontera,” in its essence, is a continual reminder that as spectators we have become accomplices to the making of borders—and that, as such, it is crucial for us to always question our own roles and perspectives as we navigate a world divided by frontiers.

We can no longer hide behind a simplified, abstract notion of border issues to the south. An overwhelming combination of rhetoric, politics, money and media would rather keep our perspectives of the border wall as facile as a single drawn line—but we need to keep trying to see more; we must not be deterred from seeing the wider spheres of consequence and context around this border. To see a true image of a border, perhaps, we need to try to see everything and everyone extending from its edges.

Tamara Toledo is a curator, artist and educator, as well as a graduate of OCAD University. She holds an MFA from York University and is presently the director/curator of Sur Gallery in Toronto.