“The first truth is the form,” instructs a deadpan, disembodied male voice in Suzy Lake’s 1975 video The Natural Way to Draw, in which the artist, caked in a layer of white paint, shades lines and contours across her face, pausing briefly to take puffs of her cigarette. The title and narration of the film derive from Kimon Nicolaïdes’s widely circulated 1941 textbook, a staple of 20th-century art school curricula whose authority Lake playfully skewers through her tongue-in-cheek performance. The 15-minute film encompasses many of the formal strategies—experiments in time-based media, performances consisting of repeated gestures and adherence to simple rules, and the use of whiteface—that the Toronto-based conceptual artist would refine over the course of her career. “You must put into your drawing most forcefully the facts which you know to be true rather than what you see,” the voice continues as Lake shades in the dimensions of her face. At the video’s conclusion, she turns directly to the camera, grinning.

For five decades and counting, Suzy Lake has created photographs, performances and films that forcefully speak to her truths, and to her political and aesthetic commitments to feminism. That feminism in turn was shaped first by a rigid, patriarchal upbringing in 1950s Detroit and her participation in anti-racist and anti-war activism in the 1960s, after which Lake moved to Montreal. The artist’s first solo exhibition in New York opened this past fall, offering a tight, provocative sampling of Lake’s conceptual practice and outlining Lake’s thematic concerns: the performance of gender and the restrictions of femininity; the prevalence of images and the process of their production; and the possibilities for new media to critique canonical art forms.

The artist’s early experiments in photography were largely documentation of performance works, such as the 1973 series Imitations of Myself, in which Lake sat at a vanity and applied whiteface. Reprinted in 2013, the early studies for this project were on display alongside a set of 24 images of the performance’s duration; the first shows Lake holding up a piece of paper scrawled with the phrase “genuine simulation of…” in red marker. This sign establishes the critical intervention the artist makes into the burgeoning feminist movement, namely exposing and recuperating the nature of artifice, further interrogated in On Stage (1972–74), a series of black-and-white images that include childhood pictures, performance documentation and photos of the artist posing for the camera in various guises and adopting a range of identities. Lake’s commentary on role-playing as a quotidian activity presages Judith Butler’s third-wave theories of performative gender, and artists such as Cindy Sherman have cited Lake as an important influence on their own artistic practices. Indeed, influence and legacy are questions Lake takes up in the recent photographs History Repeats Itself and The Game is Afoot (both 2019), in which she dresses up in period garb and places herself on a medieval chess board from the British Museum. In the latter work, she sits next to the queen and gazes at the camera with her face resting in her chin. She looks toward the viewer, disappointed that so many years on, women must still play the game on others’ terms.

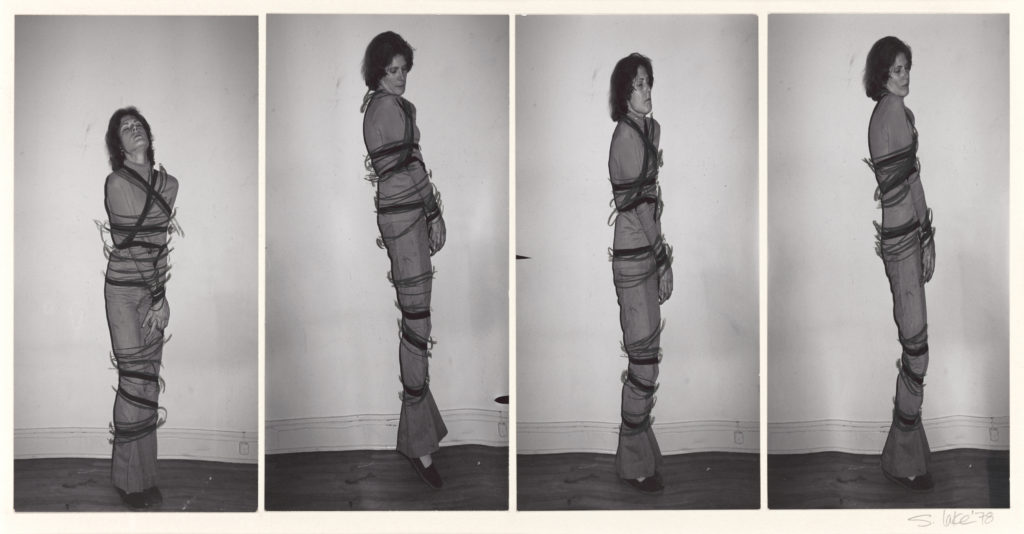

Suzy Lake, ImPositions (Study #2, maquette) (detail), 1977. Four gelatin silver prints, grease pencil and photo oil mounted to board.

Suzy Lake, ImPositions (Study #2, maquette) (detail), 1977. Four gelatin silver prints, grease pencil and photo oil mounted to board.