Le Corbusier’s Plan Obus, like his similarly monumental urban architectural designs for Paris and Rio de Janeiro, was a reductionist fantasy. Conceived in 1929 and revised for more than a decade, the unsolicited and unrealized proposal for Plan Obus was intended to thrust the French colonized city of Algiers into the modernist era by creating a megastructure that would span and dominate the existing Casbah.

While drafting his imperious plan, the famed architect is said to have developed an infatuation with Algerian women that compelled him to produce a series of erotic paintings and drawings. Akin to Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), his female figures were abstracted into anonymity, becoming exaggerated objects of his desire.

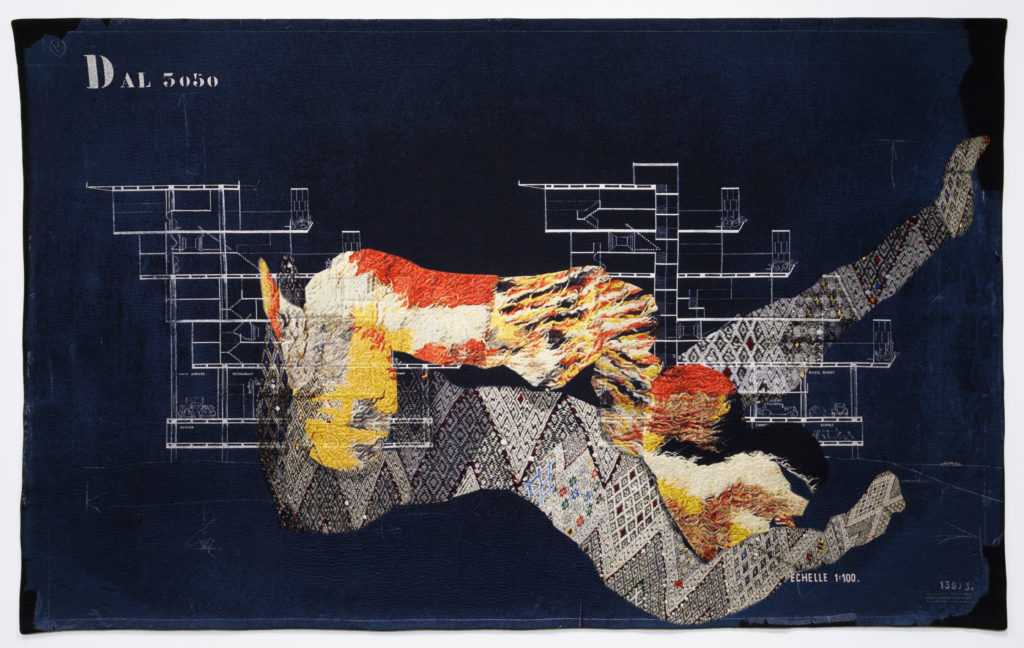

In “Bomb. Shell.” Shannon Bool makes use of Le Corbusier’s architectural plans and his erotic drawings to challenge the often domineering and appropriative character of the architect and his contemporaries. Oued Ouchaia and Maison Locative Ponsik (both 2018) are ornate and complex tapestries on which Le Corbusier’s blueprints of Plan Obus are superimposed with selections from his erotic drawing collection. Typical of her practice, Bool was meticulous in her pursuits of both research and material. She sent the finished tapestry designs to a facility in Flanders to be expertly woven on a Jacquard loom and the works were then returned to the artist at her Berlin studio for careful hand-embroidery. The curvaceous forms and splayed limbs of the figures are filled in with images of North African textile patterns, adding to the lush textural surface of the work and overwriting the sterile architectural notations in favour of a tangible human presence. Vibrant and unruly, the figures are uncontained by the plans for which they were neither considered nor consulted.

Bool carries her criticisms into the 21st century in a vignette that both refers to and mirrors interior space. Women in Their Apartment (2018) is a photograph of the master bathroom in Le Corbusier’s famous Villa Savoye overlaid with gestural erotic sketches. The flat, cubist figures are then punctuated with the gleaming, internet-breaking backside of pop-culture icon Kim Kardashian. Below sits Sugar Veins (2018), a narrow marble countertop and the exhibition’s only sculptural work. The piece alludes to an infamous episode of Snapchat drama where veining in Kardashian’s marble table was mistaken for cocaine.

The back gallery is lit with Corbusier-inspired fixtures and, like other walls in the space, painted according to his prescribed polychromatic colour palette. On apricot walls hangs a series of intimate, layered photograms that meld erotic archival postcards— similar to those the architect collected— with mock-ups of Plan Obus. Viaducts, coastlines and aerial views of the megastructure’s curved walls trace the women’s bodies. The blended pairings read as anatomical drawings, where layers are peeled back, exposing the viscera beneath. Through this coupling process Bool further emphasizes the erasure of identity inherent in sexual and colonial exploitation.

Throughout “Bomb. Shell.” Bool leverages Le Corbusier’s legacy in order to confront his breed of white male modernism. Weaving together symbols of sex, excess and power, she asserts a political critique whose relevance extends well beyond the confines of the era to the lasting societal and spatial oppression the movement imposed on disenfranchised communities, including women and colonized peoples. She readily accosts modernism’s dominant figures to question the accreditation of their celebrity. Acknowledging that these men will surely remain in the foreground of the modernist canon, Bool has deftly shown that it doesn’t mean those deserving can’t come to the front.

Shannon Bool, "Bomb. Shell", 2018.

Shannon Bool, "Bomb. Shell", 2018.

Shannon Bool, Maison Locative Ponsik, 2018. Jacquard tapestry, embroidery, 209 x 325 cm.

Shannon Bool, Maison Locative Ponsik(detail), 2018. Jacquard tapestry, embroidery, 209 x 325 cm.

Shannon Bool, "Bomb. Shell", 2018.

Shannon Bool, "Bomb. Shell", 2018.

Shannon Bool, "Bomb. Shell", 2018.

Shannon Bool, Oued Ouchaia, 2018. Jacquard tapestry, embroidery,

209 x 325 cm.

Shannon Bool, Oued Ouchaia, 2018. Jacquard tapestry, embroidery,

209 x 325 cm.