Does anything epitomize the human fascination with death and violence better than the concept of the perfect crime? In “Skull Practice,” his recent show at Wil Aballe Art Projects, Vancouver artist Scott Billings used 3D printing, robotics and computer-assisted design to examine this cultural conceit in frighteningly clinical detail.

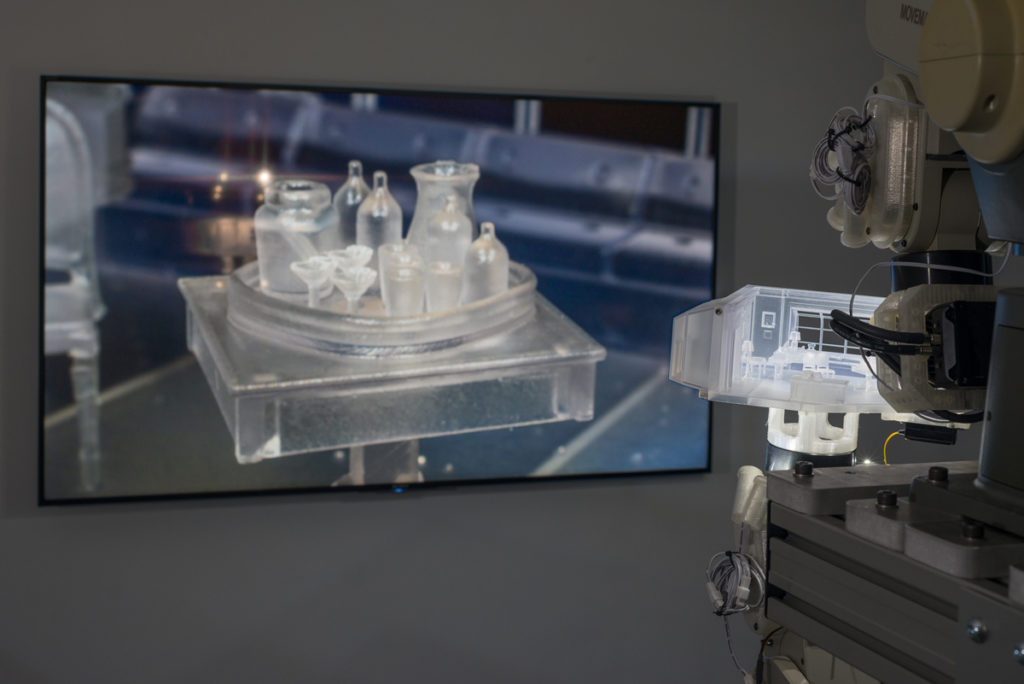

In Übermensch (2018), Billings perfectly recreates a pivotal scene from the Hitchcock thriller Rope using a camera and a tiny, 3D-printed replica set, each mounted on a robotic arm. Rope was inspired by the famous case of Leopold and Loeb who, believing a flawless crime would demonstrate their intellectual prowess, brutally murdered a 14-year-old boy.

Another work, How to Break into WAAP (2018), is a site-specific 3D-printed sculpture that constructs a theoretical escape tunnel from the basement gallery where the work is shown to Billings’s nearby studio. With excruciating precision, each segment of the proposed tunnel mimics one used in a real-life heist or escape—including the claustrophobic passage El Chapo used to break out of prison.

The clear, striated plastic produced by a 3D printer is a material Billings sees as being closer to the idealized world of a computer simulation than to the glitchier, corporeal one it inhabits. The only part of the process that engaged Billings’s hand were the keystrokes and mouse clicks that instructed the necessary computer programs—a process that raises questions of authorship and culpability. To what degree is Billings responsible for the actions of his digital creations? Does the mathematical, abstracted world in which these machinations play out make our viewership of them more comfortable?

The final work in the show, Good, Bad, Flat, Round (2012), is a two-channel video installation composed of clips from the TV show Law & Order. Given that the clips are pulled from a database by software, the duration of this generative video is infinite. Minor actors are shown describing both victims and perpetrators in pithy, throwaway phrases: “He’s the big cheese in the math department.” “She just wanted people to like her.”

As one watches dozens of the TV clips one after another, the incidental nature of these minor characters begins to sink in. In Law & Order’s world, victims exist only to move the action forward, and we are forced to wonder if these ancillary, dehumanized bodies are the reason for the show’s cult popularity. Like the robot perpetrators from Billings’s other works, do they allow us to gawk at wrongdoing guilt-free?

Through the macabre, yet strangely flat, world of computer simulations and TV procedurals, there’s one truth “Skull Practice” makes uncomfortably clear: crime only makes for good entertainment when it’s not happening to someone you know.

Scott Billings, Übermensch, 2018. Video installation, robot arms, 3D print, video camera, software, 36 inches x 25 inches x 55 inches. Installation view at Wil Aballe Art Projects. Courtesy Scott Billings and WAAP. Photo: Mike Love.

Scott Billings, Übermensch (detail), 2018. Video installation, robot arms, 3D print, video camera, software, 36 inches x 25 inches x 55 inches. Installation view at Wil Aballe Art Projects. Courtesy Scott Billings and WAAP. Photo: Mike Love.

Scott Billings, Übermensch (detail), 2018. Video installation, robot arms, 3D print, video camera, software, 36 inches x 25 inches x 55 inches. Installation view at Wil Aballe Art Projects. Courtesy Scott Billings and WAAP. Photo: Mike Love.

Scott Billings, “Skull Practice,” 2018. Exhibition view at Wil Aballe Art Projects. Courtesy Scott Billings and WAAP. Photo: Mike Love.

Scott Billings, How to Break into WAAP, 2018. 3D print. Installation view at Wil Aballe Art Projects. Courtesy Scott Billings and WAAP. Photo: Mike Love.

Scott Billings, How to Break into WAAP (detail), 2018. 3D print. Installation view at Wil Aballe Art Projects. Courtesy Scott Billings and WAAP. Photo: Mike Love.

Scott Billings, Good, Bad, Flat, Round, 2012. Dual-channel video, clips from Law & Order (1990–2010), software and database, duration infinite (generative video). Installation view at Wil Aballe Art Projects. Courtesy Scott Billings and WAAP. Photo: Mike Love.

Scott Billings, Übermensch (detail), 2018. Video installation, robot arms, 3D print, video camera, software, 36 inches x 25 inches x 55 inches. Installation view at Wil Aballe Art Projects. Courtesy Scott Billings and WAAP. Photo: Mike Love.

Scott Billings, Übermensch (detail), 2018. Video installation, robot arms, 3D print, video camera, software, 36 inches x 25 inches x 55 inches. Installation view at Wil Aballe Art Projects. Courtesy Scott Billings and WAAP. Photo: Mike Love.