On the occasion of the 57th Venice Biennale, I descended upon the international art exposition as part of a delegation comprised of 32 emerging and established Indigenous curators from Australia, New Zealand, Norway and Canada. Besides myself, the Indigenous curatorial delegation from Canada also included Michelle LaVallee, France Trépanier, Heather Igloliorte and Jaimie Isaac, and it was accompanied by Jim Logan, program officer at the Canada Council for the Arts.

For this international delegation of 32, the Venice Biennale, a site for international exchange, doubled as the site for our convergence. This was reinforced profoundly by an “official” Indigenous presence supported by the Australian and New Zealand pavilions.

My journey began with a three-day preview pass generously granted by Norway, and our seven-day itinerary was peppered with formal invitation-only openings, press previews, dinners, parties, symposia, presentations and artist talks in the Giardini, Arsenale, collateral shows and commercially supported spaces. Revisiting Venice through the opportunity of the exchange, rather than as an exhibitor or project organizer as I have in the past, offered me a different lens through which to consider its significance (or whether I want to love it or leave it).

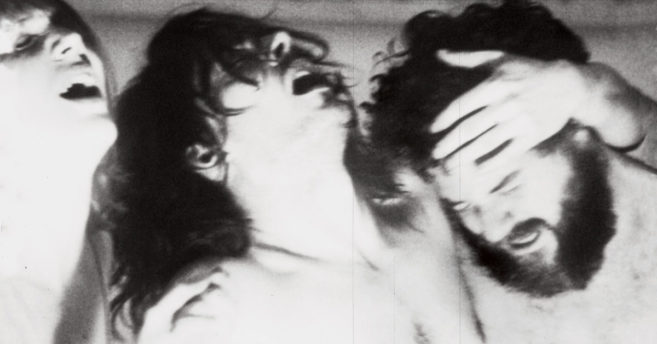

Tracey Moffatt, Hell, 2017. From the Passage series.

Tracey Moffatt, Hell, 2017. From the Passage series.

Tracey Moffatt, the first Indigenous artist to represent Australia solo at the Venice Biennale, presented “My Horizon” as its official entry. Indigenous soprano Deborah Cheetham welcomed and mesmerized the significantly sized Wednesday-morning mob at the opening with a haunting song that acknowledged protocol and presence. Inside the pavilion, two series of photo-works—Passage and Body Remembers—used Moffatt’s cinematic, film-noir style to stage and reframe personal and public dilemmas situated across time and place, cultures and memories.

Moffatt’s powerful and brutally intense video Vigil both disrupts and highlights white privilege and fragility. In it, a montage of iconic Hollywood film stars such as Elizabeth Taylor, Cary Grant and Jimmy Stewart peer and gasp in horror at the sight of refugee boats (culled and digitally altered/animated from news sources) arriving in plain sight, at a close distance, just outside their doors. Moffatt exposes the real-life global refugee crisis we have previously become familiar with from a comfortable distance, bringing it closer through inter-spliced footage and a harrowing soundtrack. The result is enthralling, eliciting paranoia and intersectional tension between “us” and “them”—or “them” and “us.”

Moffatt’s official tote bag raised attention around the issues in her artwork in a way that was simultaneously inconspicuous and bold. The black canvas tote read Indigenous Rights in yellow on one side and Refugee Rights in red on the other, infiltrating the Giardini via VIP biennale-goers and long-nosed critics who clamoured for the freebie so intensively that the Australian Pavilion reportedly ran out of its 5,000 bags on the second day of the preview. It was a beautiful, unexpected sight to see so many people campaigning—most likely, unintentionally—for global human rights issues.

Indeed, pavilion tote bags are the quintessential Biennale souvenir—portable and (occasionally) political, foldable yet fashionable, conceptually inclusive but materially (in terms of their short runs and Venice-limited availability) exclusive. They are also a perk easier to obtain—without haggling art-world credentials— than a complimentary exhibition catalogue. Dorset Fine Arts’ tote bag honored late Cape Dorset artist Kananginak Pootoogook, and it celebrated the unexpected and vital inclusion of his work in the Arsenale’s main “Viva Arte Viva” exhibition. New Zealand’s silver sling tote for Lisa Reihana’s “Emissaries” also stood out, after Moffatt’s and Pootoogook’s, as the best of the rest.

in Pursuit of Venus [infected] (2015–17) in “Lisa Reihana: Emissaries“ at the New Zealand Pavilion of the Venice Bienanle. Photo: Michael Hall. Image courtesy of New Zealand at Venice.

in Pursuit of Venus [infected] (2015–17) in “Lisa Reihana: Emissaries“ at the New Zealand Pavilion of the Venice Bienanle. Photo: Michael Hall. Image courtesy of New Zealand at Venice.

The New Zealand Pavilion, occupying the Tese dell’Isolotto at the farthermost end of the Arsenale’s gutted and historic maritime buildings, was the ideal site for Maori artist Lisa Reihana’s technically complex panoramic video In Pursuit of Venus [infected].

Reihana’s flawless projection, running 23.5 metres long, is a cinematic landscape that brings to life, recalls and disrupts the colonial memory embedded in 19th-century wallpaper that depicts the voyages of Captain Cook and other explorers’ voyages across the Pacific. Reihana charts the global narrative of discovery from a land-, sea- and sky-based Pacific perspective, animating Indigenous presence as post-colonial scenes of contact to shift perspectives and disrupt encounters.

This epic work is subtly set against a background soundscape that includes Cook’s prized ticking clock—a crucial navigation and mapping aid for colonial forces. Reihana’s projection is also bookended by larger-than-life portraits that she identifies as English naturalist Joseph Banks and the Tahitian Chief Mourner, and it is also accompanied by a sculptural installation of five telescope-like viewing stations focused on specific moments of exploration and wonder.

Reko Rennie’s three-channel video installation OA RR (2017) reflects a road trip to Kamilaroi land in New South Wales—a site near where his grandmother was born, and then removed as a child in a reclaimed Rolls Royce. It is in “Personal Structures” at Palazzo Mora concurrently to the Venice Biennale. Photo: Courtesy the artist.

Reko Rennie’s three-channel video installation OA RR (2017) reflects a road trip to Kamilaroi land in New South Wales—a site near where his grandmother was born, and then removed as a child in a reclaimed Rolls Royce. It is in “Personal Structures” at Palazzo Mora concurrently to the Venice Biennale. Photo: Courtesy the artist.

These exhibitions offered by Moffatt and Reihana support a distinct worldview—a truthful representation that counters the master narrative embedded in the vernacular of (still unraveling) global histories.

However, Indigeneity also gets mined in many instances across the Biennale’s major “Viva Arte Viva” exhibition—a mining heavily supported by an ethnographic gaze.

Curator Christine Macel opens the Arsenale component of “Viva Arte Viva,” for instance, with Juan Downey’s “going native” National Geographic-esque 1979 video installation The Circle of Fires, which attempted to close a gap in the late 1970s between Indigenous and non-Indigenous. This approach is simply unsettling and unnecessary in 2017.

Video works showing concurrently in Venice by Indigenous artists Reko Rennie (whose OA RR is on view in the group show “Personal Structures” at Palazzo Mora) and Marcella Ernest (whose Wah.Shka and Nibiin Water Song were shown on Certosa Island during the first week of the Biennale) would have mattered more than Downey’s. Both Rennie and Ernest offer encounters of authenticity that Macel’s “Viva Arte Viva” fails at, even as Macel ostensibly puts this value forward as one of her curatorial aims.

A view of Bernardo Oyarzun’s Werken (2017) in the Chilean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Via Chilean Pavilion press site.

A view of Bernardo Oyarzun’s Werken (2017) in the Chilean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Via Chilean Pavilion press site.

Exploitation and appropriation (ironically, not only in Canada) were issues triggered by a number of chapters of the Biennale.

In fact, one of the first headlines out of the gate during Venice preview week called out Damien Hirst’s copying of an Ife head, a 14th-century Nigerian artwork, for his new series Treasures From the Wreck of the Unbelievable showing concurrently at Palazzo Grassi.

Chile’s pavilion featured an installation of more than 1,000 Mapuche kollong ritual masks; these were made by 40 Mapuche artists identified only as part of a “group of Indigenous inhabitants of southcentral Chile and southwestern Argentina” in the press release. The masks were part of the wider installation Werken (2017), orchestrated by and credited to artist Bernardo Oyarzun; the show also includes an LED display scrolling some 6,900 surviving Mapuche names around the exhibition space.

Though Oyarzun has identified himself as being of some Mapuchean ancestry in a few prior interviews, his relationship to this culture is not grounded in or indicated in the pavilion’s press release or curatorial framework. As a result, the Mapuche’s general corporeal (or documentation-credited) absence here counters the critique of Werken’s intended presence.

Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto (far right) with six members of the Huni Kuin people inside the installation Um Sagrado Lugar (Sacred Place) at the Venice Biennale’s “Viva Arte Viva” exhibition. Photo: Jacopo Salvi. Courtesy La Biennale de Venezia.

Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto (far right) with six members of the Huni Kuin people inside the installation Um Sagrado Lugar (Sacred Place) at the Venice Biennale’s “Viva Arte Viva” exhibition. Photo: Jacopo Salvi. Courtesy La Biennale de Venezia.

More troubling yet was Brazilian Ernesto Neto’s Um Sagrado Lugar (Sacred Place) in the “Viva Arte Viva” section identified by Macel as the “Pavilion of Shamans.” Neto’s motivations are unclear—except for the space he creates as a ringleader, choreographing spectacle and the fetishization of primitivism by placing six Txanas, all members of the Huni Kuin people, on display as his art under a tent.

The Goethe-Institut-supported talk around Um Sagrado Lugar (Sacred Place), held during the opening events on May 12, was divided. The Huni Kuins’ translated words spoke to the urgency and responsibility we have to the natural world. Neto, whose presence evoked the cult leader of the mission in the 2015 film Embrace of the Serpent, rambled between artspeak, capitalist patter and hobby ethnography. He proclaimed, “This work is for sale,” indicating 40 per cent of the sale would go to the gallery/dealer, 40 per cent to the artist, and 20 per cent to the Huni Kuin. Any true sense or sign of collaboration in this work was trumped by Neto’s self-serving arrogance, and by the lingering colonial gestures he perpetuated.

The Brazil Pavilion bounced back with the successful “Cinthia Marcelle: Hunting Ground”—my pick as the “best in show.” Though many of the national pavilions had a weighted, embellished feel, a component of Marcelle’s installation with a sloping steel-grate floor stuffed with small rocks used gravity and pressure in a different way: namely, some of the rocks would drop away, freed from the traffic of visitors walking upon the grid.

Respite from the entrenched weight of the monolithic pavilions in the Giardini and Arsenale was uncovered in the Zimbabwe Pavilion, tucked unassumingly away on a third floor off of a Grand Canal walkway in Venice’s Castello district. The exhibition “Deconstructing Boundaries: Exploring Ideas of Belonging” offered a critical moment of reflection without the bells and whistles (or big budget) of many other Venice projects.

Dana Whabira’s Circles of Uncertainty drawings, for instance, and Admire Kamudzengerere and Rachel Monosov’s Transcultural Protocol performance addressed human development, resilience and social histories as it is possible to elegantly and viscerally work them through in contemporary art practices.

That these Zimbabwe Pavilion works on identity, inclusion and exclusion were tucked away in an inconspicuous location, away from the frenzies and spotlights of “Viva Arte Viva” and other major Biennale presentations, seems at once suitable and ironic given that they actually deliver on the intention of a broad-thinking, mind-opening exhibition.

The thoughtful curation of “Deconstructing Boundaries” prompts viewers to consider the exercise of and impetus for decolonizing the canon from its invented/imagined center, dust off the resulting rubble, and determinedly join the ranks.

Ryan Rice, Kanien’kehá:ka, is the Delaney Chair in Indigenous Visual Culture at OCAD University.

A clarification was made to this article on May 30, 2017. It clarifies that Tracey Moffatt’s exhibition at the Australia Pavilion is the first solo show there by an Indigenous artist, as others have participated in past group shows. A correction was also made on June 2, 2017, regarding the date of the wallpaper referenced in Lisa Reihana’s work.

A view of the Australia Pavilion, which featured its first Indigenous solo artist, Tracey Moffatt, this year. Photo: Australia Council for the Arts.

A view of the Australia Pavilion, which featured its first Indigenous solo artist, Tracey Moffatt, this year. Photo: Australia Council for the Arts.