Currently, there is a meticulously crafted, conceptual carnival game on the executive floor of a bank tower in downtown Toronto. It’s a game no one can physically play, though its mental teasings are many. The name of the game is Cup and Ball and it is Toronto-based artist Roula Partheniou’s new commission for the BMO Project Room, curated by Dawn Cain.

Partheniou has long worked in the expanded field of sculpture to create decoys. Best known for her mimetic work, Partheniou skillfully creates signifiers that disguise themselves as the signified: the cast-resin and foam balloon against the ceiling of the gallery that looks just like a real helium balloon (Untethered (Balloon), 2017), for example, or the wood-and-acrylic box of Lucky Elephant popcorn that appears to be a real box of popcorn (Cup and Ball, 2018). Indeed, if it weren’t for the artist’s deliberate play with different degrees of verisimilitude—sometimes an object looks identical to the thing it’s copying, while other times something is slightly changed (a label removed, or another detail missing)—those who happen upon her work might not realize it’s an art object at all. So often it’s the moment in which the trick is revealed that elicits such an awesome response in viewers.

Partheniou’s BMO installation is arranged as two primary elements: the warm white cup-and-ball “game,” which the viewer sees when they enter the Project Room, and the rainbow-coloured set of “prizes” arranged on shelves, which the viewer sees once they turn around. These two elements face each other, and while each element on its own might be simple, their relations are complex, made all the more so when displayed in this context. The simple provocation of a game—to throw a ball into a cup—becomes an overwhelming ask. With hundreds of stacks of cups, all of those little balls sitting in the pail waiting to be tossed, there’s an uncanny feeling that something just isn’t quite right. The stacked cups are arranged to make them appear like a sprawling city, and the fact that the skyline of Toronto can be seen through the window just beyond the towers of cups adds to the work’s dizzying effect. What might have begun as a fun game now feels vertiginous, unsettling.

Roula Partheniou, Cup and Ball, 2018. Lacquer and acrylic on wood. Installation view at BMO Project Room. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Roula Partheniou, Cup and Ball, 2018. Acrylic on wood, cast resin. Installation view at BMO Project Room. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Roula Partheniou, Cup and Ball, 2018. Enamel and acrylic on wood, cast resin. Installation view at BMO Project Room. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Roula Partheniou, Ticket Stack (detail), 2018. Acrylic on wood. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Roula Partheniou and Michelle Astrug, Scratch ticket invitation to Cup and Ball, 2018. Scratch card ink on laser printed, matte-coated board, penny. Photo: Roula Partheniou.

As I take in Cup and Ball, I think of beer pong (one of the rambunctious drinking games of a frat-house kegger), even though the artist’s intricately carved wood cups painted in a matte, off-white are more elegant than the polystyrene of beer pong’s red solo cup. I think of styrofoam coffee cups set out with a carafe by a secretary for an office meeting. I think of boys’ clubs, of men’s clubs. These readings start to slip away as soon as my eyes move to another cup, or acclimate to the warmth of Partheniou’s visual renderings (her cups, made of wood and paint, look almost ceramic). Has Partheniou undone the disposability of male-identified culture with a crafting so often coded as feminine? Perhaps I’m projecting something onto the work that isn’t really there, although this play of suggestion is at the heart of Partheniou’s practice.

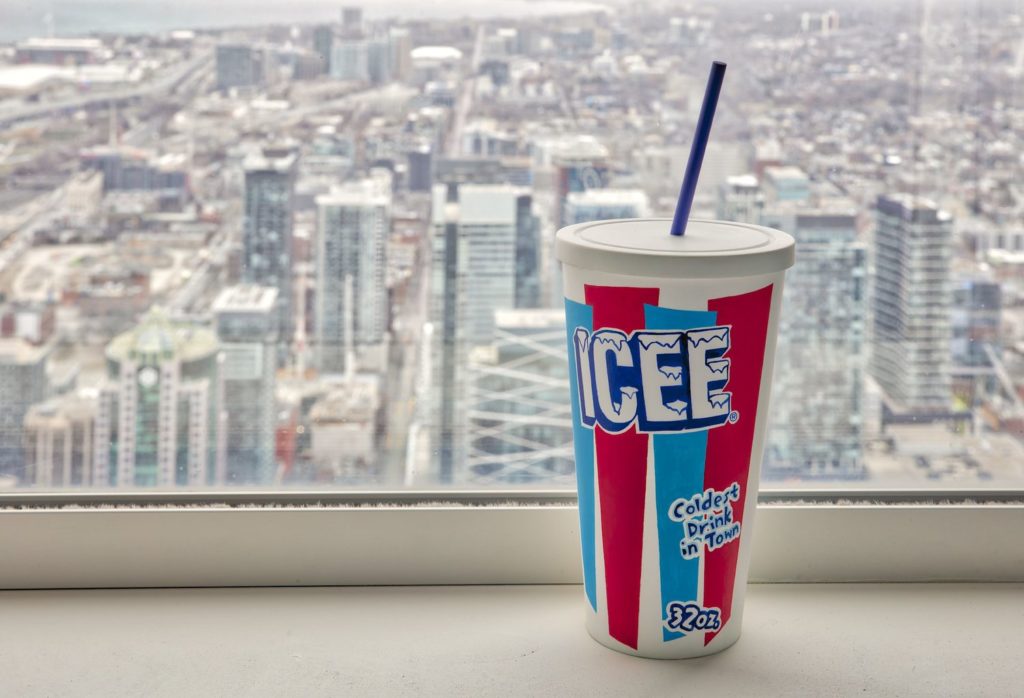

The artist shared an anecdote with me: one night when the building had closed, one of the cleaning staff walked into the Project Room straight toward the ICEE cup sitting on the window sill. When they picked up the cup they realized—at the moment of touch—that it was not really a cup at all, but part of the art. This event, which was caught on CCTV camera, was a moment of rupture—the cleaning staff aren’t supposed to enter the Project Room, given the special needs of art maintenance. In a sense it extends Partheniou’s work to its logical conclusion. Her cast-resin bouncy balls invite tactility (I want to pick one up and throw it against the wall, feel it ricochet back to my hand) just as the cast-resin lollypops might make you salivate; but these embodied desires are refused by the spatial semantics of an art installation. Placed on the shelf, set in from the edge, the objects register as not-to-be-touched. But on first glance, the ICEE cup is read as outside the bounds of the art space. Because it reads as accidental, it also reads as something to be tossed in the trash.

The thematic refrain in Partheniou’s practice—that the game is rigged—takes on a more politicized charge in this space, extending beyond the artist’s visual “rigging” of objects to the ideological notion that the economic system itself is rigged. Installed in the nook-like Project Room in the tallest bank tower in the country, in the thick of Toronto’s financial district, Cup and Ball transmutes the illusory play of Partheniou’s decoy objects into a commentary on the inevitabilities of a late-capitalist system. Through these site-specific, sculptural semantics, Partheniou has created an installation that reflects the premises of game theory: from the strategic relations of the different players in the game, to the connotations of competition and risk. Once you see it this way, it’s hard to see anything else.

When I turn to leave the installation, the large rendering of the “We’re #1” foamy hand familiar to sports fans catches my eye. Walking through the corridor to the elevator, I pass by other works of contemporary Canadian art from BMO’s collection. Now I’m seeing them differently. Just a few feet away from the Project Room, Toronto-based artist Jon Sasaki’s single-channel video Dead End, Eastern Market, Detroit (2015) plays on a loop. In the video, the artist is in the driver’s seat of a white van, which is stuck in a baffling sideways orientation between two brick walls in an alleyway. The artist moves the van back a bit, then forward a bit, then back a bit, and then forward, in a Sisyphean attempt at parallel parking. This is not just play, if play is ever just play. Sasaki is trying his best to get out of a situation that seems impossible to get into in the first place. The game is his to lose.

Roula Partheniou, ICEE Cup (detail), 2018. Acrylic on wood. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Roula Partheniou, ICEE Cup (detail), 2018. Acrylic on wood. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.