In Form Follows Fiction: Art and Artists in Toronto, Luis Jacob has made a remarkable contribution to thinking about this place, Toronto. Perhaps it is because he is an artist, and not a historian, and an artist for whom Toronto figures as a subject of work, that he is able to conceive history differently, to conceive it as a species of imagination. Perhaps this is the only way a history could happen here: if we imagined it.

Jacob claims that his book “is not a history,” or at least not a history of art, in spite of its 98 artists and reproductions of archival documents and artworks ranging from 1788 to 2016 making it look like a history book. Rather the book, he says, “explores some of the recurrent patterns that artists have developed to articulate their sense of place in one of North America’s largest cities.” This is no depiction, of images of the streets of Toronto, for instance, but an exploration of the manner in which the city impresses itself on the imagination. The play of place and its artistic product is not necessarily a conscious process. Every place has its narratives, stories it tells itself. Sometimes they are stories of dominance, sometimes of loss and defeat. Jacob suggests that Toronto’s grand narrative, counterintuitively, is one of erasure. Undisclosed as a historical process, erasure leads to a failure of narrative even while it functions as its unconscious determination. For Jacob, this is a legacy of Toronto’s colonial placemaking.

Any accounting of Toronto art must contend with this history and not content itself with documenting a sequence of autonomous artistic acts, as related as they might be in their vanguardist trajectory—that is, one that erases its own past. Form Follows Fiction is cultural history not art history. To this end, Jacob identifies two defining figures he says are specific to Toronto—the tangled garden and the vacant lot. Neither symbols nor metaphors, they are generative of forms grounding artistic practice. It is as if we are tripped up by what is always already underfoot, by what we tend to overlook and undervalue—and here Jacob quotes Painters Eleven’s Harold Town: the “imperceptible thrusting of a carpet world.” Yet the two figures are entwinned. “The motif of the tangled garden articulates the ignored, repressed or misrecognized aspects of local experience that are overlooked by deracinated desires,” Jacob writes, the latter of which are embodied in the functional void of the vacant lot. The vacant lot is not merely empty; it is the monetary reserve of capitalism’s “compulsive repudiation of existing form.” The ubiquity of vacant lots inures us to capitalism’s sleight-of-hand erasure of “the forms of life that pre-existed them,” making us oblivious to “the circularity of this re-enacted disavowal.”

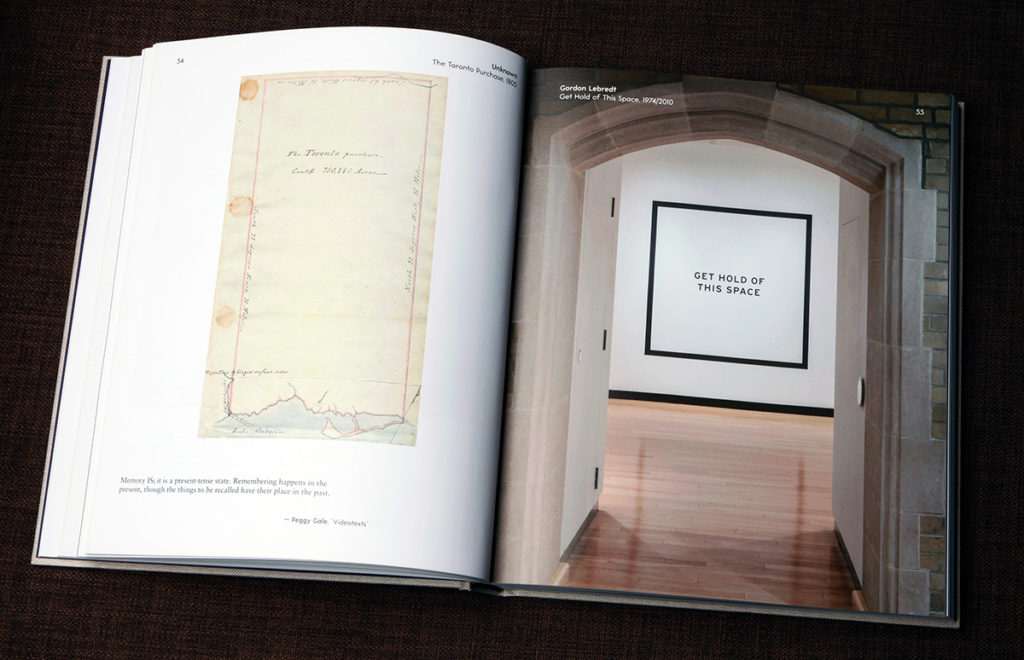

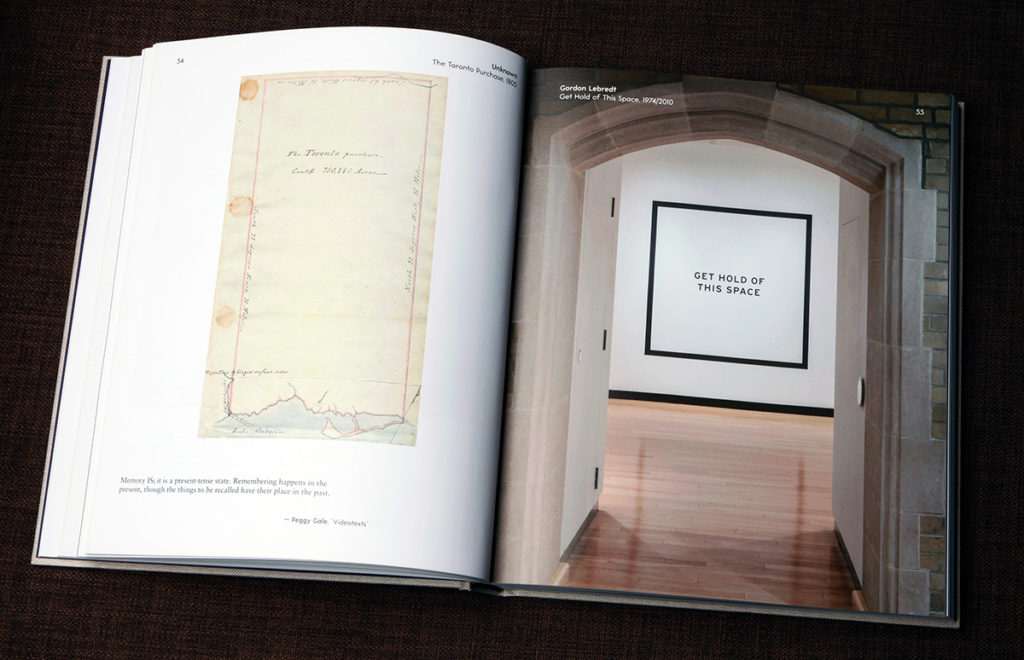

Inside pages from Form Follows Fiction with images of (from left) an 1805 map of the Toronto Purchase and Gordon Lebredt's Get Hold of This Space, 1974/2010.

Inside pages from Form Follows Fiction with images of (from left) Jeff Thomas's Dreamscape Street Car Dundas Street, 1987, and Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge's Work in Progress, 1980–2006.

For Jacob, the template of this repudiation is the so-called Toronto Purchase of 1787, the agreement between the British Crown and the Mississaugas of the Credit. He illustrates this with the blank slate of an 1805 surveyor’s map that disavows any particularity of terrain or previous settlement as well as several complementary plans partitioning parcels of property that were to become the city of Toronto. Another signal image, for Jacob, of “the ostensible vacancy of repudiated experience” is a 1957 photomontage that whites out what the city was about to wipe out in order to build its modernist city hall: about a dozen downtown city blocks of teeming urban life, a community that included the city’s first Chinatown.

This is the vacated ground upon which Toronto artists make their work, one riven by trauma—although these historical artifacts are not commonly thought of as part of Toronto’s artistic canon. The test, or task, for Jacob comes in putting this cultural diagnostic into practice, seeing it as instituting enough artwork to think of it henceforth as tradition. It is to Jacob’s credit that he does not see an opposition between “vacancy” or “plenitude” but rather insists that we register their tension: “One perspective witnesses a proliferation of forms of life on the same spot where, from another perspective, we are induced to see a lack.” Nonetheless, he allocates artists to each of these categories. Jon Sasaki’s microbial swabbing of Group of Seven palettes (2012) or David Armstrong-Six’s video Track it Around (2000), showing the artist trailing a gummy substance on his feet around the streets, are among those works that stand for the carpet-world underfoot. Given that these are singular examples of the artists’ works, not representative of their corpuses as a whole, one sometimes wonders whether Jacob has inventively constellated themes rather than discovered determining patterns. Similarly, one might question, for example, Gordon Lebredt’s Get Hold of This Space (1974/2010), which Jacob calls an “allotment on the gallery walls,” or General Idea’s graph-paper letterhead of 1974, as artistic emblems of the vacant lot. That Lebredt conceived this work as a Winnipeg artist, several years before he moved to Toronto, strains the specificity of Jacob’s argument. Moreover, could General Idea have known the suppressed history they possibly were reproducing, as is suggested when Jacob juxtaposes their letterhead to a 1788 plan of Toronto? Is this relationship pseudomorphic or a genuine insight on Jacob’s part? Whatever the case, Jacob has opened new terrain. For instance, in pursuing this thought of the vacant lot he has uncovered and raised from the rubble, so to speak, an interesting series of works about demolition by Peter MacCallum, General Idea, Tom Dean and David Anderson.

Jacob assembles a larger cast of artists by spatializing his model—the “twinned images” of tangled garden and vacant lot—along horizontal and vertical axes. (His model itself is generative, or allegorical, in its capacity of extension and inclusion.) “The distribution of things in our surroundings—their arrangement near or far in the landscape, up or down on the ladder—speaks of the ways that we assign value,” writes Jacob, which usually means a lack of regard for what is local in favour of the allure of art elsewhere. We Can’t Compete and We Won’t Compete (both 2012), two crocheted wall hangings by Deirdre Logue and Allyson Mitchell, express refusal of these premises while Benny Nemerofsky Ramsay’s Audition Tape (2003) mocks competition in the art world. In such works, says Jacob, “the tangled garden and its views-from-below function as ‘other’ to the reciprocal image of the art-scene conceived as a pedestal for solitary ascendancy”—the beauty contest metaphor long before appropriated by General Idea for their Miss General Idea Pageant (1970 on).

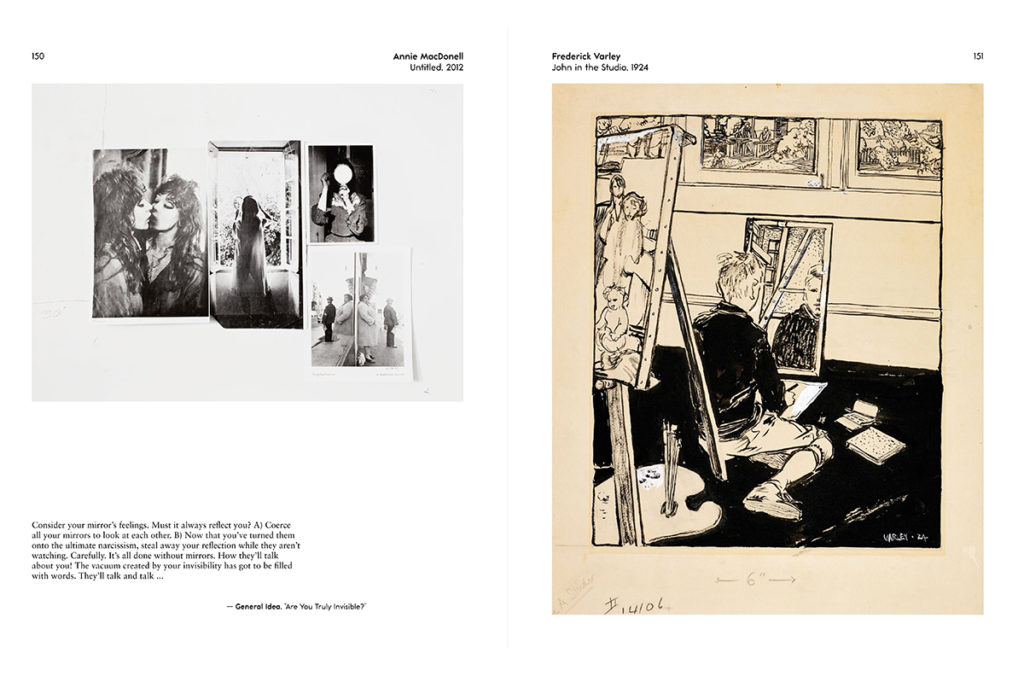

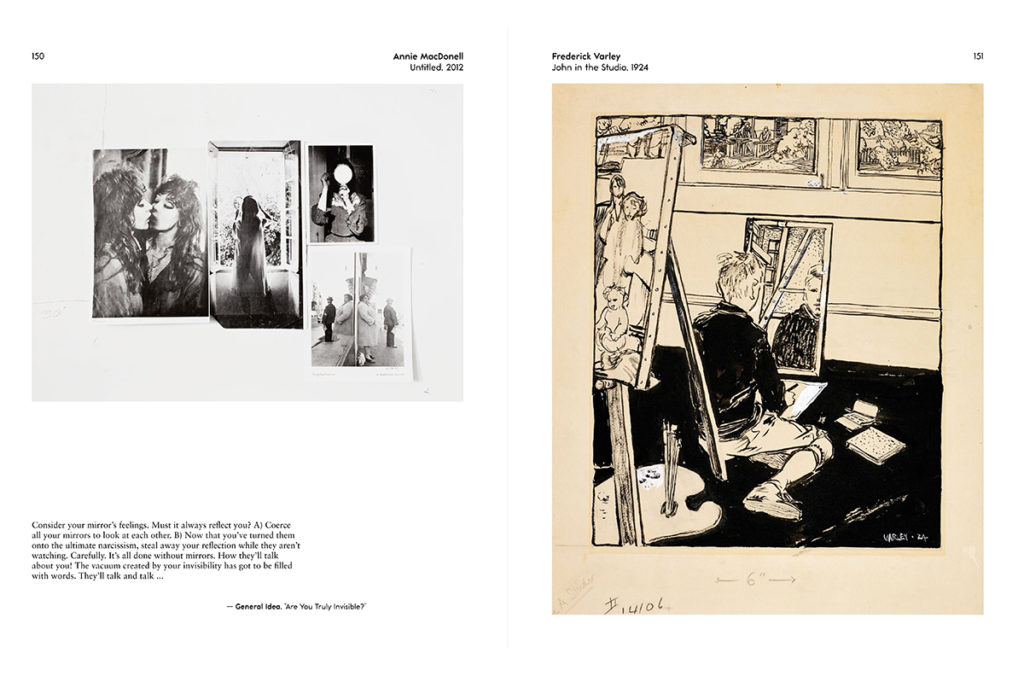

Inside pages from Form Follows Fiction with images of (from left) Annie MacDonell's Untitled, 2012, and Frederick Varley's John in the Studio, 1924.

Inside pages from Form Follows Fiction with images of (from left) Suzy Lake's A Genuine Simulation of..., 1973–4, and Bridget Moser's The Mirror Has Two Faces, 2016.

Inside pages from Form Follows Fiction with images of (from left) Carl Beam's Self-Portrait in My Christian Dior Bathing-Suit, 1980, and Joanne Tod's The Magic of Sao Paulo, 1985.

It is here that Jacob makes an odd, or adventurous, move in finding affiliation with a longer history of Canadian art. He suggests that the valorization of high and low already existed in the popular icons of the Group of Seven, for instance in the minor scale of Arthur Lismer’s Undergrowth (1946) and the major chord of Lawren Harris’s Isolation Peak, Rocky Mountains (1930), their titles alone indicative of the lowly and the transcendent and the values that attend such a distinction.

Evidently it was the title of J.E.H. MacDonald’s 1916 painting The Tangled Garden that inspired Jacob’s concept and let the Group of Seven sneak into this Toronto history. By the end of his book, the vacant lot has been invaded and overrun by the entangled artificial undergrowth of the self-fashioning art community itself, a place within a place Jacob sometimes calls “paradise” after Tom Dean’s 1987 This is Paradise mural in the Cameron House tavern, a gathering point for Queen Street artists from the early 1980s on. Now “three metaphors serve for us to define three interrelated visions of ‘place’ in the self-disclosing endurance of its social and historical dimension: the tangled garden, the artist-bar, and the family tree,” Jacob writes, although the latter two are treated as species of the first. Not surprisingly, these are images of when this art scene was in formation, picturing itself to itself allegorically in the image of the artist-bar or imagining its allegiances in the metaphor of the family tree. The artist-bar is partly represented by the paintings of the ChromaZone collective but also by Colin Campbell’s video Bad Girls (1980), which significantly is also an allegory of entry into the art scene. The family tree fictionally stands for the family one chooses, an “imaginary re-membering” as Jacob nicely puts it. But his choices of David Buchan’s early Roots (1979) and later works by Sarindar Dhaliwal and Deanna Bowen remind us that all was not equal in the uneven reception of queer insiders and racialized outsiders in the origins of the Toronto’s contemporary art community.

Little did they know, in these degraded gardens of the flowers of evil, artists were fabricating the city’s culture, perhaps not recognized by the patrician class yet but in the end registering the trauma of the city’s inauguration on stolen Indigenous land. Culture comes from below, Jacob implies, not from on high: “Culture is the social site of encounter of vulnerable identities, the unsettling place of their wounding or healing transformations.”

Artworks both register and redress inflictions; form follows affliction, one might say! “Wounds become scars…scars become style,” Jacob quotes Barbara Fischer from her 1996 “Love Gasoline” exhibition. Estrangement yields to artifice: “self-portraiture enacts the flamboyant performance of wounds as style.” By aligning this notion of the stylistic wound to the split identities of General Idea’s Borderline Case (1972), Jacob accounts for the self-fashioning performativity that flourished at the beginning of the contemporary art scene. But he traces the basic instability of vulnerable identities in unsettling places beyond the supposed autonomy of Toronto’s artistic underground back to Canada’s colonial origins, suturing the wounds of the present to those of the past.

Front cover of Form Follows Fiction: Art and Artists in Toronto with Oliver Husain's Purfled Promises (video still), 2009. Photo Iris Ng.

Front cover of Form Follows Fiction: Art and Artists in Toronto with Oliver Husain's Purfled Promises (video still), 2009. Photo Iris Ng.

Margaret Atwood and Northrop Frye are Jacob’s guides here, directing us back to the plight of early settlers and their garrison mentality—for instance to Susanna Moodie, author of Roughing it in the Bush (1852) and Life in the Clearings Versus the Bush (1853), the latter title anticipating Jacob’s nomenclature of vacant lot and tangled garden. It was the English immigrant Moodie who experienced, according to Jacob, “a frightening vacancy in the imagination,” ungrounded on the very spot she stood, but it is Atwood’s imaginative retelling in her own The Journals of Susanna Moodie (1970), or rather her ventriloquism manifested there, that is Jacob’s (literary) model for the artistic strategies to follow in Toronto. “The failure of narrative and the void in the imagination announce themselves, but they do so performatively—theatrically—in the diagnostic re-enactment of another author who consciously impersonates symptoms of estrangement as a posture,” he writes.

Appealing as they are, Atwood’s Survival and Frye’s The Bush Garden are some 50 years old. These books were written at a moment of cultural awakening, of literary and economic nationalism, that was coincidental with recognition of Canada as a “pure colony” of America, complicit with its war in Vietnam. These writers looked to Canada’s colonial history and its literary representations to understand their own dilemma: the defeatism of the Canadian psyche. Can we appeal to these writers to understand where we are now, especially when the immigration that has so transformed Toronto since then is not on a continuum with that of Susanna Moodie’s but is of a different, diversifying pattern altogether? Step aside Margaret Atwood; Dionne Brand, cited several times by Jacob, is the rightful contemporary chronicler of this new city in formation.

There is a cost to Jacob’s imaginative reliance on Atwood and Frye, which is to turn his book into cultural, rather than contemporary art, history. When Frye writes that “the question of identity is primarily a cultural and imaginative question,” we understand that the identity in question in Jacob’s book is that of the city of Toronto firstly and its artists secondarily. This has the virtue of discounting an erasive vanguardist tradition that derives from elsewhere in favour of something rooted here. But at the same time the long arc of his analysis could be seen to restore a conservative tradition, to maintain a Loyalist story of defeat, and to recuperate artists we have long let go: the Group of Seven, Harold Town, etc. It is not enough forward looking, recognizing the diverse changes since then in the art scene, which his book, nonetheless, is evidence of. But this would fail to recognize what is exciting and inventive in what Jacob proposes or imagines for us, and the ground he prepares for rethinking or thinking otherwise the values of an art scene. Form Follows Fiction is synthetic, not analytic. It is a well-structured fiction as well as an imaginative history. When Jacob writes, “The city’s amnesia towards its own cultural ecology is inversely reflected in the historian’s dawning realization of proliferating and interconnecting forms of life,” he may have been thinking of himself, an artist for whom love of Toronto has made him an innovative historian.

Form Follows Fiction: Art and Artists in Toronto is published by the Art Museum at the University of Toronto in partnership with Black Dog Press.