Etel Adnan’s rhythmic reading from her book of poetry Sea and Fog in the Otolith Group’s film I See Infinite Distance Between Any Point and Another (2014) forms one element of “Open Justice,” an online exhibition that provokes viewers to think about worldmaking and the possibilities of retelling histories—and futures. “We went to the moon once, under a propitious weather, and loved each other in ways we couldn’t achieve on our terrestrial habitat,” she reads. Paired with images of organism growth, expansion and connection, Adnan’s meditative reading gestures toward new forms and ideas for rethinking the so-called end of the world.

The theme (and feeling) of catastrophe in “Open Justice” is deeply relevant to today’s global political and social ecology, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The works address the global rise in fascist politics, increasing violence toward migrant, queer and racialized people, and climate change that is inching humanity closer than ever to cataclysm. Emerging from this state of planetary tension, the films in the exhibition ask how we might reimagine what justice looks and feels like in our approaches to worldmaking.

The Otolith Group, I See Infinite Distance Between Any Point And Another, 2014. HD video, 33 min 33 sec.

The Otolith Group, I See Infinite Distance Between Any Point And Another, 2014. HD video, 33 min 33 sec.

Ronald Rose-Antoinette has carefully curated a selection of videos that disrupts the understanding that catastrophe is irreversible. “Open Justice” asks audiences to consider those populations who are subject to different forms of violence—and how for those marked as undeserving of humanity (the bodies of Indigenous, Black, queer and trans people), the end of the world has already happened many times before. The works show different planes of human and non-human temporality, and position the earth as a resilient witness to the devastation of all bodies, including the terrestrial. Tidal Locking (2019), by Jamilah Sabur, collapses temporal and spatial limits by intersecting ocean rhythms and planetary orbits. The vertical layout of the videos—of microorganisms juxtaposed with space and technology—transmutes the assumption of a horizontal or linear temporal plane and shows us how time and space can rearticulate geography and futurity. Beatriz Santiago Muñoz’s Gosila (2018) mixes scenes of Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria to reference transformation and reconstruction. In one, a man in a vehicle arrives at a flooded road, stopped behind another truck. Both drivers then proceed through the washed-out route. As they drive, the image is suddenly flipped, with the water now flowing at the top of the screen, giving the viewer a sense of a disordered world, a sense of feeling “washed over.” In ALTIPLANO (2018), Malena Szlam fuses textured topographies of the northern Chilean desert, a land marked by resource extraction. The haunting cadence of the soundscape—produced by infrasound recordings found in nature, such as those of blue whales, geysers and volcanos—brings the body of the viewer into the scarred landscape that Szlam forges, and reflects the resilience of the earth after human devastation.

Jamilah Sabur, Tidal Locking, 2019. Video, 5 min.

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Gosila, 2018. HD video and 16mm transferred to HD video, 10 min.

Malena Szlam, ALTIPLANO, 2018. 35mm film, color, sound, 15 min 30 sec.

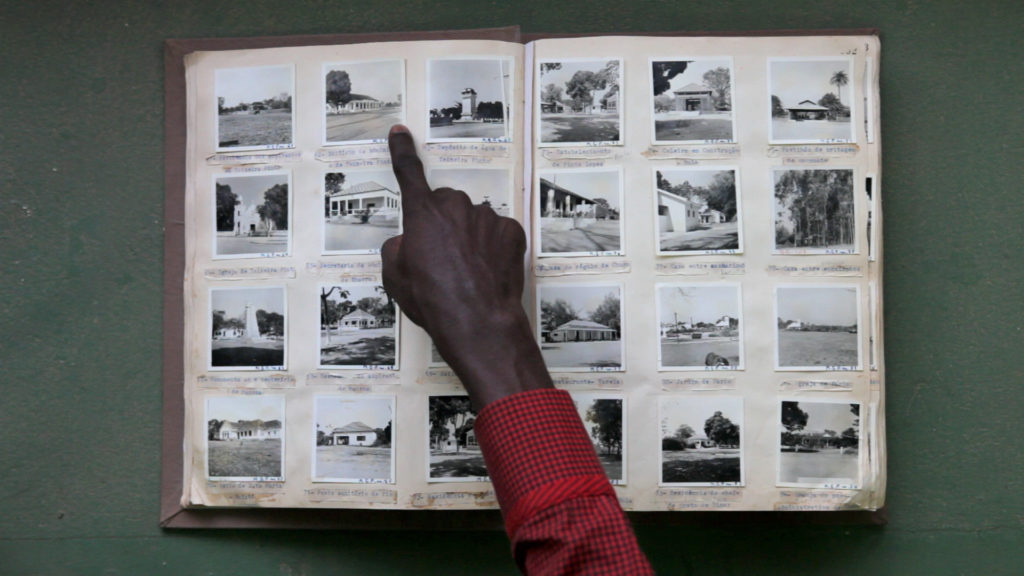

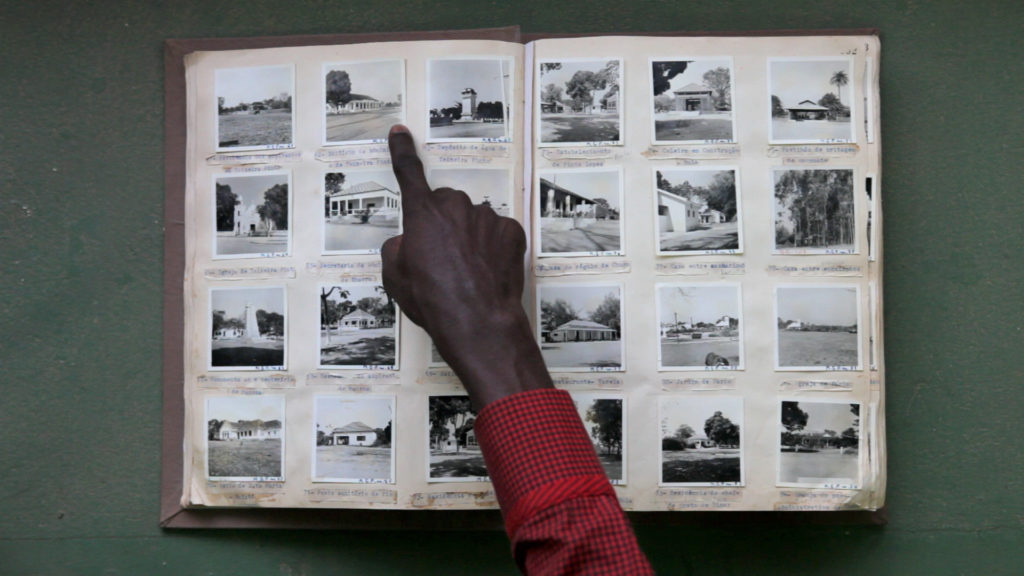

Filipa César’s The Embassy (2011) intervenes in Guinea-Bissau’s colonial archives by offering counter memory and grappling with the possibilities of postcolonial futures. The film reads against the grain of a Portuguese colonist’s midcentury photo album, a collection of images of Guinea-Bissau that demonstrates the author’s voyeurism. Guinean archivist Armano Lona’s hands move through the album as his voice retells the narrative of colonial history, inviting us to recalibrate our viewership. Situated on a boat in the middle of the ocean, an adapted Forum Theatre play by Bouba Touré, Traana – Temporary Migrant (1977–2017), restaged here by Raphaël Grisey and Kàddu Yaraax, follows a group of Senegalese migrants who leave their homes behind to head to Europe in search of better futures. The play references the sociopolitical ruptures in their communities caused by colonialism and the civil war.

The assembly of films in Open Justice exposes the injustices underpinning the conditions that produce catastrophe, and invites us to reconsider how we imagine new, just worlds. What journeys will we take, and what shores might we arrive on?

Filipa César, The Embassy, 2011. HD video, color, sound. 27 min.

Raphaël Grisey, Bouba Touré and Kàddu Yaraax, Traana – Temporary Migrant, 1977–2017. Video, 27 min.

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Gosila, 2018. HD video and 16mm transferred to HD video, 10 min.

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Gosila, 2018. HD video and 16mm transferred to HD video, 10 min.