Montreal artist Numa Amun is something of an enigma. Case in point: In advance of a visit to Quebec City earlier this fall to see “Raccord,” his solo exhibition at the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec for the 2019 MNBAQ Contemporary Art Award (past winners include Diane Morin and Carl Trahan), I asked about the possibility of a studio visit. Out of the question, I was told, even the curator of the award exhibition had not been granted access to the artist’s studio. A colleague in Montreal confirmed, recounting an invitation to participate in an exhibition she was curating, which, when finally accepted, still came with a proviso: “I had to make a leap of blind faith up until he came to install the work,” she wrote. “But it was so rewarding. People who have been in his studio can be counted on one hand.”

It’s a minor but telling anecdote that, as the MNBAQ exhibition proves, is much less, if at all, about some kind of projected mystique than a singular artistic vision and intensity. The eight paintings by Numa (his given name in reverse, by which he is best known) assembled for “Raccord” each took roughly a year to produce, from 2009 to 2017. Some had been shown previously, most notably in a 2018 exhibition/intervention in an east-end Montreal church, but until now have never been seen together as a complete set or cycle.

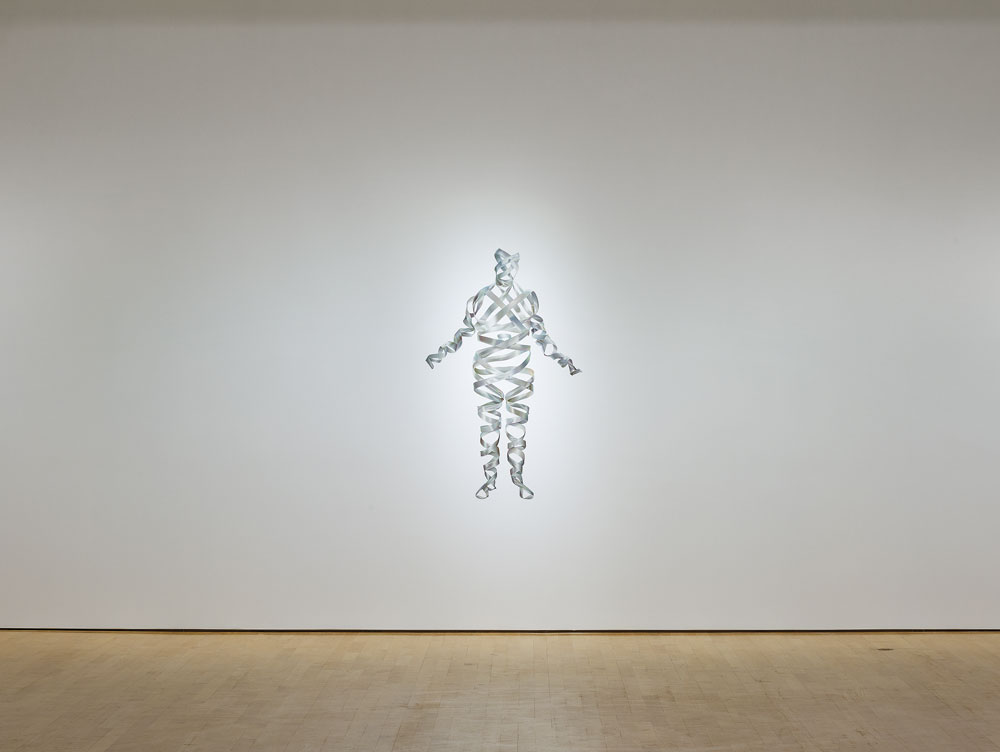

The exhibition is framed as chapters in what the artist calls a “liturgical” or “spiritual” journey from womb to grave and beyond. Beginning with the faint figure of a child in utero, Numa’s painted story moves through adolescence, adulthood and death, each stage charged with the existential weight of innocence, uncertainty and vulnerability. Seamlessly installed flush to the gallery walls (there are no canvas edges, only the open gallery space as frame), each painting is a precise study in figuration and abstraction: when you step close you realize Numa’s life-size, naked subjects are variously rendered with an almost imperceptible glow of finely painted geometric patterns, lines and numbers. They float in the gallery, both real and unreal. In the final work, Corps sombre (2016), a female form stands inside a dark, otherworldly prism. Whether this is a trap or transcendence is difficult to say, but perhaps the point is that either way the end is just another beginning.

Numa Amun,

Numa Amun,