History, in the Western sense, is made up of textbooks, monuments and an official narrative. How do you then go about generating a lineage of those who have a history of being excluded from the “official” narrative? I embark on this review of Desire Change: Contemporary Feminist Art in Canada taking tips from Amy Fung’s semi-manifesto “How to Review Art as a Feminist and Other Speculative Intents” featured within the book. As Fung brilliantly states: “A feminist art review could only be a killjoy times a thousand.”

Instead of taking the fully fledged feminist killjoy route, however, I aim for the following in this review: to convey the daunting nature of the Desire Change project and how it articulates difficult conversations that the dominant narrative sweeps under the rug. Rather than discount this publication as another coffee-table art book, I hope to make the case for its importance in archiving marginalized legacies and their contemporary manifestations, in order to ensure feminist futures.

Desire Change explicitly situates itself at the margins, conscious not to replicate the colonial framework of exclusion and hierarchical devaluation that can so easily lead to generational silencing. Co-published by McGill-Queen’s University Press with Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art (MAWA) and edited by Heather Davis with the help of managing editor Nicole Burisch, this tome points to the complexities and nuances of embarking on any history-recording endeavour. Yet the collective nature of the publication succeeds in taking stock of contemporary feminist cultural production in a pluralistic and intersectional way, bringing together essays that discuss critical artists deeply invested in the production of political thought.

Rather than assimilate all texts into a feminism singular, Desire Change presents art practices stemming from diverse feminisms, prefacing the different needs and desires from varied communities across these contested lands. The publication leads us into a conversation of convergent themes and urgent issues that feminist cultural producers are currently grappling with, articulated through three points of desire: reciprocal intersectionality, decolonization and restructuring via feminist practice.

This book announces an examination of “Contemporary Feminist Art in Canada”—but why use the label “feminist art” in 2017? What does feminist art signify within the colonial borders of the Canadian nation-state?

With regards to intersections of feminisms and the arts, continuous evidence shows that equality in the arts has not been achieved. In 2015, Canadian Art’s feature “Canada’s Galleries Fall Short” made clear there is still much work to be done to dismantle the “white boys’ club” in Canadian art galleries’ programming. And we have only to look at the very recent #NotSurprised rallying campaign to understand the implications of this boys’ club. These are the contemporary working conditions for artists and arts workers in North America.

But let’s narrow it back down to Canada: this book was published this year, in 2017, the year that Canada is in the midst of its sesquicentennial revelling—and, perhaps, reckoning. Although not explicitly branded as a resistance to the Canada 150 project, the book arrives in a timely manner to disrupt the self-congratulatory narrative of settler colonial patriarchy’s “home on Native land.”

The publication is bookended by a genealogy and a timeline that survey the historical context for feminist art production in Canada, stemming from the so-called “Second Wave” era of the 1960s and ’70s. Both of these texts map out the formative moments that led to transformative change within the Canadian feminist art landscape and set the stage for the present contemporary practices that have developed.

Kristina Huneault and Janice Anderson’s genealogical “herstory” discusses artist-run culture that bloomed in the 1970s, the DIY tendencies that continued into the ’80s, and also how Canadian feminist artists did things differently than their more renowned counterparts in the South. However, that is not to say that Canadian feminist art of these decades wasn’t without its essentializing and whitewashing—because it did manifest both these things. The importance in surveying these moments—be they successes, failures, exclusions or challenges—is so that we may learn from the past and dismantle imperial discourses.

Gina Badger’s appendix was created by collaboratively assembling a timeline of important moments in the production of feminist art in Canada. Badger compiled her findings from 57 responses received from the Canadian arts community, a model of how art history writing can become a grassroots and collective endeavour.

The timeline begins in 1963 with Edith Josie, an elder from the Gwich’in nation, and the debut of her column “Here Are the News” in the Whitehorse Star—a timeline entry contributed by artist Jeneen Frei Njootli. Badger makes explicit that “no matter what, any story about feminism in North America is indebted to the labour and cultural production of Indigenous women.”

In the book’s vital middle section, “Desiring Change: Decolonization,” both Ellyn Walker and Tanya Lukin Linklater’s texts engage with questions of reconciliation.

Walker makes reference to conciliation, the word David Garneau points to as being the correct term for what should be materializing, as conciliation refers to “the action of bringing into harmony” and presupposes Indigenous sovereignty. Garneau has elsewhere discussed the institutionalized reconciliation project as being a liberal fabrication, as the word reconciliation itself “refers to the repair of a previously existing harmonious relationship” (available as a PDF)—which has never been the case in Canada.

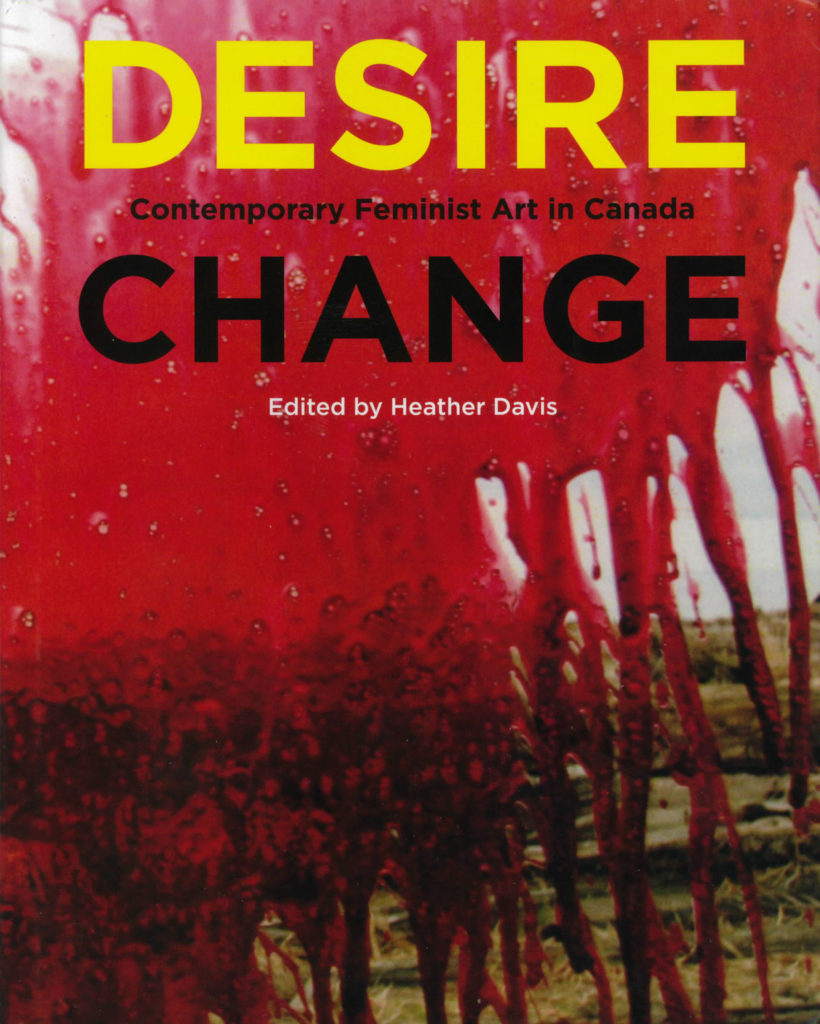

This truth is exemplified in Walker’s discussion of Rebecca Belmore’s practice—which frequently memorializes missing and murdered Indigenous women, attesting to the myth of a once harmonious settler-colonial relationship. Belmore’s pivotal piece Fountain (2005) also features on the cover of the publication, its spray of blood reinforcing both the violence of colonization and the artist’s powerful legacy.

In parallel, Linklater discusses the solo work of Lisa Jackson and Peter Morin, as well as the collaborative work of Morin, Ayumi Goto and Leah Decter, as enacting a “radical reconciliation” which de-centres whiteness and settler priorities within the reconciliation project. Morin, Goto and Decter’s collaboration Performing Canada (2014) powerfully achieves this de-centering by revealing that the nation-state is itself a performance. The artists here suggest that if Canada is a myth that is continuously being performed—like gender roles, as Judith Butler once pointed out—then its script can be re-written and re-performed.

Likewise, in her chapter “Mother Me,” Jenny Western looks at the work of Faye HeavyShield, Danis Goulet and Kenneth Lavallee as a way to rewrite the colonial script surrounding Indigenous motherhood in Canada, re-indigenizing portrayals of motherhood.

The dismantling of the naturalized nation-state and its subjects continues through a questioning of Canadian identity. In Sheila Petty’s rendering of Camille Turner’s work, she highlights how Turner enacts a Black diasporic gaze to disrupt the normalized representation of who gets to be considered Canadian. Petty demonstrates how the assumption of neutrality in an idealized white Canadian identity is subverted in Turner’s parodic performances, such as her ongoing Miss Canadiana, where she counters the erasure of Black Canadian experience.

Erasure can also turn into alienation, as seen in Karin Cope’s examination of Alvis Choi/Alvis Parsley’s performative persona Captain Kernel. This green-faced alien persona literally evokes alienation, and “what it means to be racially or culturally excluded, not to belong, to be neither here nor there, in-between, trans, neither boy nor girl, neither human nor non-human, but still in need of love, in need of appropriate pronouns.”

There are many ways one can be excluded and alienated when othered by homogenizing binaries. Dismantling socially constructed categories of gender, sexuality, race and nationhood through queering, satirization and denaturalization are key to questioning the norms that formulate desire. These intersections are initially defined in the book’s first section, “Desire: Intersections of Sexuality, Gender, Race,” and are taken up throughout the entire book.

Alice Ming Wai Jim writes about confrontations with notions of colonial desire and cultural appropriation in ethnic apparel, while Thérèse St-Gelais highlights how desire has been represented by Olivia Boudreau, Christine Major, Myriam Jacob-Allard and Les Fermières Obsédées in Quebec. Jayne Wark focuses on the potential of abjection from a lesbian queer Canadian perspective, as rendered in the work of Rosalie Favell, Allyson Mitchell and the collaborations of Shawna Dempsey and Lorri Millan, where humour often figures as a tool of resistance.

Rather than enact an “add women and stir” approach (a method coined by Charlotte Bunch), the artists within these pages challenge the very power structures that uphold white supremacy and colonial patriarchy, and seek to formulate structures that can sustain their new world-making.

The final section of the book, “Institutional Critique and Feminist Praxis,” addresses precisely this dilemma; it points to rebuilding as being the best bet for what feminist cultural producers can get behind in current-day Canada.

In this final section, Kathleen Ritter engages Lorna Brown, Allyson Clay, Marian Penner Bancroft, Kathy Slade, Jin-me Yoon and Anne Ramsden on a reflection of how they were undertaking subversive efforts in Vancouver circa 1989; author Noni Brynjolson charts the origins of MAWA’s peer-based mentorship program and its community influences, articulating the challenges and growth that came with organizing across differences; and Amber Christensen, Lauren Fournier and Daniella Sanader spark a discussion with Allyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue about their ongoing Feminist Art Gallery (FAG) project and the implications of creating spaces for feminist art that spur alternate art economies while resisting institutionalization.

In the same section, Amy Fung and cheyanne turions’s texts—both titled on a turn of phrase after Helen Molesworth’s “How to Install Art as a Feminist”—offer crucial “how-to” advice on the dos and don’ts of feminist restructuring, whether that be through art writing or curating.

A publication like Desire Change is crucial in the current Canada 150 climate of settler amnesia. Archiving and memorializing are necessary in disrupting the nation-state, as these tactics honour the lives and legacies that challenge the oppressive structures that capitalist heteropatriarchy is founded upon. The recording of marginalized pasts and presents is essential to the sustainable continuation and growth of a social and political movement to ensure futurities.

In co-publishing Desire Change, it seems MAWA’s original aims in initiating a mentorship program so that younger artists didn’t have to constantly be “reinventing the wheel anew,” as current MAWA co-executive director Shawna Dempsey recounts, still hold true. We are able to collectively imagine new futures when we can access and learn from the past and self-reflexively assess our current situation to continue the work that precedes us.

Instead of inserting themselves within existing colonial frameworks, the artists, writers and arts workers in Desire Change imagine and create alternate structures for a more sustainable ecosystem. By taking up the legacies of their foremothers, they continue the work of regenerative reforestation.

Valérie Frappier is an editorial intern at Canadian Art.

Art from Rebecca Belmore's 2005 work Fountain is featured on the cover of Desire Change: Contemporary Feminist Art in Canada, published in 2017 by McGill-Queen's University Press and Mentoring Artists for Women's Art.

Art from Rebecca Belmore's 2005 work Fountain is featured on the cover of Desire Change: Contemporary Feminist Art in Canada, published in 2017 by McGill-Queen's University Press and Mentoring Artists for Women's Art.