Like my first solo apartment, I didn’t realize how badly I needed Leilah Weinraub’s SHAKEDOWN until I had it. Weinraub’s mixtape-style documentary unearths two years’ worth of grimy footage she shot in the early 2000s while working as the in-house videographer for an underground Black lesbian strip-show and party series of the same name in Los Angeles, California. Opening with a tracklist and introduction that foreshadow the key characters and noteworthy scenes to come, SHAKEDOWN cycles through an observational portrait of the party’s brief but densely influential existence. A trip down memory lane, adorned with warm colours and late-90s pre-HDTV grit, audiences are brought behind the scenes into the sweaty centre of the action, and then back out onto the quiet, palm tree–lined streets of LA, under the echo of the party’s thumping bass and the looming threat of dawn.

“I don’t mean to appall anybody but this is a gay club,” announces party founder Ronnie-Ron over the microphone while we shuffle through a stream of Shakedown Productions flyers. “Please don’t disrespect my dancers. They dance for girls—if you don’t like it, just have a seat boo boo. Okay?” Nothing about this party, or this film, is implicit. The party understands and caters to its audience, as does Weinraub, who never shies away from an opportunity to show exactly what it is like to be there.

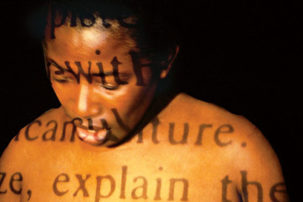

We meet Egypt—one of the party’s most legendary dancers—on her living room couch, more than a decade after Weinraub began documenting the party and almost eight years after it closed its doors due to police harassment. Egypt softly narrates her memories and her own journey to queerness through the exploration of erotic performance. “I do things as Egypt that I would never do as Aisha,” she attests. “Like what?” asks Weinraub over a flashback to Egypt stomping onto the dance floor, outfitted from head to toe in bright pink tie-dye. “I can be a Barbie, I can be a kitten, I can be S&M, I can beat your ass. I can do whatever I want to do. Nobody fucks with Egypt.”

Leilah Weinraub, SHAKEDOWN (still), 2018. Courtesy the artist.

“I told Ronnie-Ron to start Shakedown,” explains Ms. Mahogany. A trans woman and Mother of the House of Fish, Ms. Mahogany mentored many of Shakedown’s young performers and also joins us from her living room. Over an archive of video footage, she paints a picture of the local queer entertainment history from which the party series extends. Interjecting to make sure Weinraub asks her about Divas for Dollars, the drag shows she used to host in the ’80s, she describes, “I had Ms. Catch One, Mr. Catch One, Master Catch One and Ms. Full Figured.” “What’s ‘Master’?” asks Weinraub, intrigued. “It’s the stag. Ronnie-Ron was the first to win that.” Ms. Mahongany speaks about Ronnie-Ron as her son. The network was familial, and the queer entertainment scene provided a home for those looking to be free, even if only for a moment.

In SHAKEDOWN Weinraub offers us an example of a past world where the fissure of prioritizing Black queer and trans joy, within fervent anti-Blackness, inspires imaginings of comparable futures.

At once a time capsule and a blueprint of Black femme self-determined world-making, Weinraub’s 82-minute immersive offering gave me my 2018 “look at what’s possible!” moment. SHAKEDOWN fundamentally challenged my social exhaustion with the mainstream conversation about the importance of representation in media by forcing me to reckon with my own longing for the kind of space it portrayed. A response to an absence—yes—but also a hunger for the vision it took to create that space in the land of the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), and in the wake of Rodney King. Amidst the ever-present global inundation of images of brutality against Black people, thinking through SHAKEDOWN alongside other artworks that portray themes of anti-Black state violence provides renewed insights into how art can impact our social world.

During the Q&A for SHAKEDOWN’s Canadian premiere at Toronto’s Images Festival last April, Weinraub said she began filming 10 years after the 1992 LA riots—the uprising in response to the acquittal of all officers involved in King’s beating that was heard around the world. Citing a party supporter in the film who says he was “here before they built the freeway,” Weinraub explained that after the riots the city of LA transformed its built environment to further segregate Black communities. These sorts of very violent actions were, if nothing else, the familiar tightening of social controls around the location, movements and free associations of Black people. In many ways, given its space and time, Shakedown—the party—emerged as a result of that socio-political atmosphere. And so, through the party’s prioritizing of Black queer and trans peoples—in an explicitly sex–positive (and sex work–positive) space—Shakedown built something that directly undermined the state’s destructive efforts, so much so that it quickly became targeted by the police as a threat.

In Weinraub’s dreamlike portrait, we drift in and out of confrontation with the city’s harsh social realities toward the intimate dressing rooms and crowded dance floors. The film’s narrative and footage continually jump through space and time—pulling us from the vibrant party into the calm, confident reflections of the performers in their afterlives—as if in an effort to preserve its elusiveness and to never quite fit within our grasp. But what Weinraub demonstrates clearly, in the varied testimonies of care, the dancers’ self-defining proclamations and the partygoers’ fearless rage and joy, are tears in the social order of the day. In spite of anti-Black and heteronormative socio-political strictures, Shakedown fostered a radical moment for respite and recharge. In other words, the film captures an example of what Arthur Jafa, in a recent talk at the Art Gallery of Ontario, called “a fissure.”

Flying through a genealogy of modern European artists’ confrontations with African artifacts, Jafa, the cinematographer-turned-contemporary artist, explained that “much of the power of these objects was bound up in their radical alienation” from the “contexts in which they [the objects] found themselves.” That power, he went on to say, “had nothing to do with the cultural specificity of ‘this is an African artifact’; it’s just something in terms of the Western cosmology around Blackness and whiteness, that if you put a Black object in a white space it produces a certain type of fissure.” This fissure—or tear, or new opening—is what I believe Weinraub saw at Shakedown. This fissure is what she was finally able to capture in film after more than a decade of working with her three-year-long video archive of the party, and shooting several follow-up interviews after Shakedown had ended.

Jafa and Weinraub, through their works’ skewing of temporal logics, signal to what we can learn from reading socially engaged art in relation to its time and space. As seen in his widely acclaimed Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death (2016), Jafa’s dialectical montage of found footage—which takes separate, and often distinct, clips and places them alongside each other to create auxiliary meanings—spans multiple generations. Overlaid with Kanye West’s gospel-inspired “Ultralight Beam,” the compilation produces a fraught yet entirely orienting moment in which viewers are pushed to face the fact of Blackness, and the inescapable presentness of moments past. Jafa’s video confronts its audience with unrelenting and unrestrained trauma that is decidedly non-linear, and in this way challenges our perceived distances from the times in which the captured moments took place. Effectively, the “then” of past incidents of violence and trauma becomes the “now.” Alternatively, in SHAKEDOWN, Weinraub offers us an example of a past world where the fissure of prioritizing Black queer and trans joy, within fervent anti-Blackness, inspires imaginings of comparable futures. In this way, she presents something similar to what is articulated by queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz, whose scholarship on “queer utopian memory” signals to the utility of resurfacing blissful, subjective and emotionally preserved moments in helping to reorient present-day freedom struggles toward future world-making.

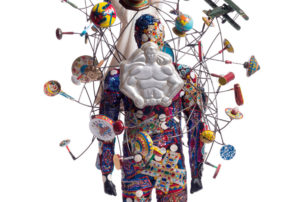

A Soundsuit by Nick Cave. Photo: Facebook.

A Soundsuit by Nick Cave. Photo: Facebook.

What SHAKEDOWN offers in terms of a reading of LA in the decades after the riots is furthered alongside other works that draw on similar themes, and emerge from similar contexts. For example, visual artist Nick Cave, who constructed his first Soundsuit in the months following the LA riots, presents another work for thought. In a 2014 interview at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, Cave explained that the first suit emerged from his difficulty consuming the overwhelming media coverage of the riots, particularly as an African-American man. Channelling these feelings into material objects, Cave began collecting twigs, which he eventually constructed into the first of an ongoing series of suits that now spans more than 25 years. The Soundsuits are made largely out of found or otherwise discarded materials that are sculpted, embroidered, adorned and re-fashioned into what he calls “secondary skins or suits of armour.” They anonymize the wearer—erasing race, class and gender. Moreover, the suits are often animated and performed in groups, which invokes themes of protection, movement and isolation within a collective, and gestures to a sound that is often only seen and not heard.

In a recent interview for Canadian Art, Cave remarked:

I am using sound as a form of alarm. Sound doesn’t always have to be heard. You can hear sound through pattern, [and] how pattern is set up on a surface to create rhythm. Colour can also create a sense of sound. Just use a police car for example: if you don’t hear the siren but you see the red lights, you know what that means. Sound is signal, so therefore it may be approached that way…

SHAKEDOWN, through the work of Weinraub and Tim Dewit, who scored the film, also explores social sound’s signalling and audibility. They blend pops, kicks and bass bumps with intermittent noise cancellation meant to conjure the sound that lingers and haunts the party-goer once they’ve left the event—the proverbial ringing in your ears, the (inaudible) memory of queer futures against the backdrop of state violence—the kind that racialized or marginalized peoples know so well.

Cave’s work toward sound through the visual renegotiates approaches to both seeing/being seen and hearing/being heard. The Soundsuits speak to the violence of social silencing and erasure, as well as the new ways of being together and communicating with each other that emerge from them. Cave’s work alerts us to the sounds that can be either heard or aurally unheard—perhaps only seen— yet still trigger us in much the same way that we are triggered by police violence, which now echoes a history much longer than what’s been documented, but is still audible at all times and in all ways.

SHAKEDOWN, like Cave’s Soundsuits and like Jafa’s Love, invokes the weight of collective memories and calls on us to consider contexts that are both present and seemingly past. When read together, these works reflect fissures of Blackness in white worlds—some, like SHAKEDOWN, go so far as to document what can emerge from them. Attending to the questions of time, space and place propels considerations of how the visuality, materiality and audibility of Blackness is de- and re-fashioned toward the creation of liminal spaces—the spaces before and after whatever we already think is possible. As much as it is a utopian memory, Weinraub’s offering is one of possibility, and it is through these reflections that we get closer to a tomorrow that is more liveable than today.

SHAKEDOWN screens in Toronto on Wednesday, November 7, 2018, a co-presentation by Black Gold + Images Festival.