Jon Sasaki‘s exhibition at the Richmond Art Gallery, “We First Need a Boat for the Rising Tide to Lift Us,” is focused on documentation of the artist’s titular July 2019 boat-making performance in the Fraser River. While the artist, in his performance, takes on a frustrating position, this work is steeped in a calm, carefully constructed and delicately balanced sense of personal journey.

In this action, Sasaki seems lost at times, but still maintains a clean (and honestly, quite radiant) posture, activating a waterscape that surrounds, and might devour, him. At once playful and painful, “We First Need a Boat” is tinged with darkness—and Sasaki’s signature gallows humour.

In many ways, this exhibition attempts to (re)imagine and (re)tackle some of the harsh realities Japanese Canadians had to cope with after their internment during the Second World War. Specifically, the work evokes the dire economic conditions that alternately resulted from, and also forced, Japanese Canadians to restart life from scratch or change life paths.

Installation view of Jon Sasaki's exhibition “We First Need a Boat for the Rising Tide to Lift Us” at the Richmond Art Gallery. Photo: Michael Love.

Installation view of Jon Sasaki's exhibition “We First Need a Boat for the Rising Tide to Lift Us” at the Richmond Art Gallery. Photo: Michael Love.

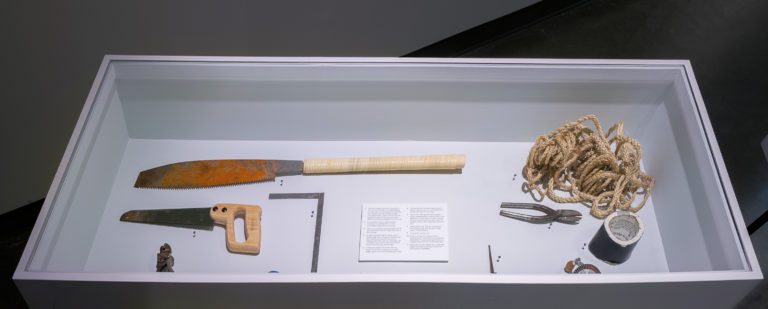

Jon Sasaki's exhibition “We First Need a Boat for the Rising Tide to Lift Us” at the Richmond Art Gallery includes a display of Japanese boat-building tools he used in a July 2019 performance. Photo: Michael Love.

Jon Sasaki's exhibition “We First Need a Boat for the Rising Tide to Lift Us” at the Richmond Art Gallery includes a display of Japanese boat-building tools he used in a July 2019 performance. Photo: Michael Love.

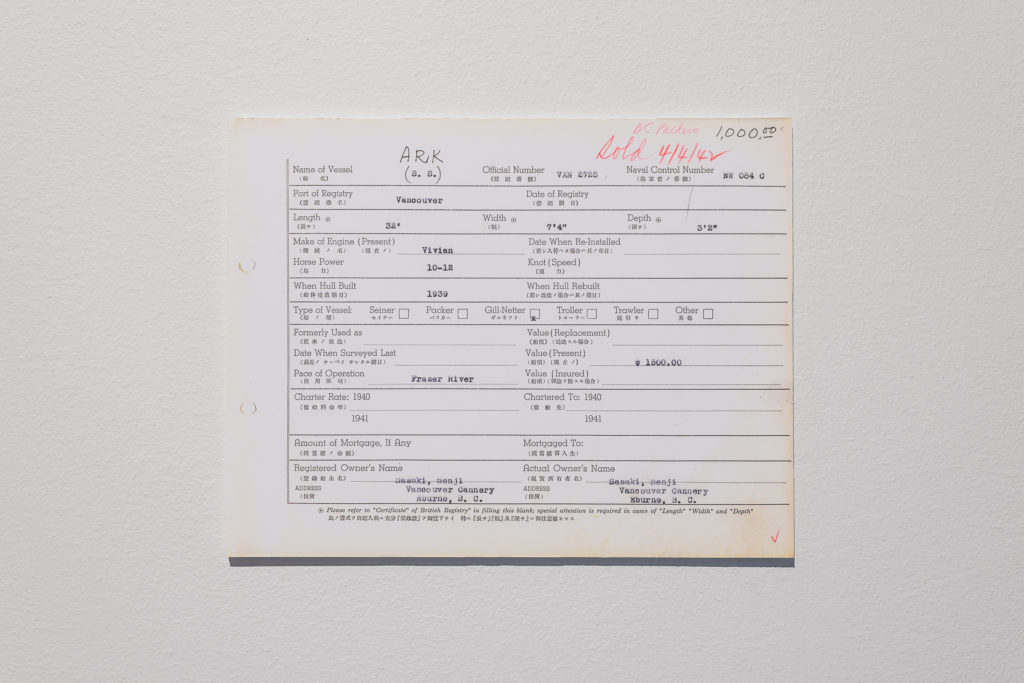

Sasaki’s grandfather, for one, was a fisherman in the Fraser River Delta in the 1940s. After the internment camps, he made his way to Ontario to start a new life—because the government-sanctioned confiscation of his boat and fishing tools during internment left him with few other options. Survival, then, became both a need and a yearning. Making connections to the experience of his grandfather, Sasaki, in July 2019, returned to his family’s pre-internment home of Steveston, BC. There, he walked into the Fraser River and attempted, in waist-high waters, to use Japanese boat-building tools to construct a vessel he could return to shore in.

Sasaki made this attempt without much seafaring knowledge, resulting in a kind of elaborate failure. At the same time, there was a kind of success, as Sasaki’s precarious situation and isolated solitude evoked his personal and familial struggles within a Canadian society long in denial of or indifferent to historical internment and segregation.

In the gallery, a video of the performance is accompanied by a vintage sound machine that produces the noise of ocean waves; the disconnect between sound and image sonically reinforces the field of isolation.

Ample solitude, outdoor settings and wrestling with the unfamiliar—all these elements contribute to the idealistic, languishing quality of Sasaki’s performances. In 2017, he initiated a similar performance near Markham, Ontario, based more on ideas of the romantic hero alone in an outdoor struggle. Often in his work, Sasaki is a lone character thrown into a futile situation.

This archival form at the Richmond Art Gallery indicates the expropriation and sale of a boat belonging to one of Jon Sasaki's ancestors during the Second World War Japanese Canadian internment. Photo: Michael Love.

This archival form at the Richmond Art Gallery indicates the expropriation and sale of a boat belonging to one of Jon Sasaki's ancestors during the Second World War Japanese Canadian internment. Photo: Michael Love.

A sense of courage and endurance in the face of looming self-doubt and insecurity also resonates in Adaptability (2019), the other video included in Sasaki’s exhibition. Here, two agile hands (belonging to origami artist Osamu Miyabe) skillfully, tirelessly turn one piece of paper into a variety of shapes. Some of these shapes resemble a house, a boat or something in between. Towards the end, the paper tears slightly due to its continuous folding.

The tenacity and resilience, as well as pliability and wear, suggested by Adaptability recalls Sasaki’s acts of making and unmaking in BC. His work recognizes the initiative that Japanese Canadians in the post-internment era took to make new lives, to have strength and hope. It also forces the question of why such initiative was needed in the first place, and what institutionalized cruelties made such initiative necessary.

In his earnest quest to honour wider histories and his own family’s truth, Sasaki might seem the loneliest man in the world. But he also remains, and he persists—a tendency that connects him, still, to his grandfather, his community, and their determination.

Jon Sasaki performing at Garry Point, BC, in July 2019. Photo: Richmond Art Gallery.

Jon Sasaki performing at Garry Point, BC, in July 2019. Photo: Richmond Art Gallery.