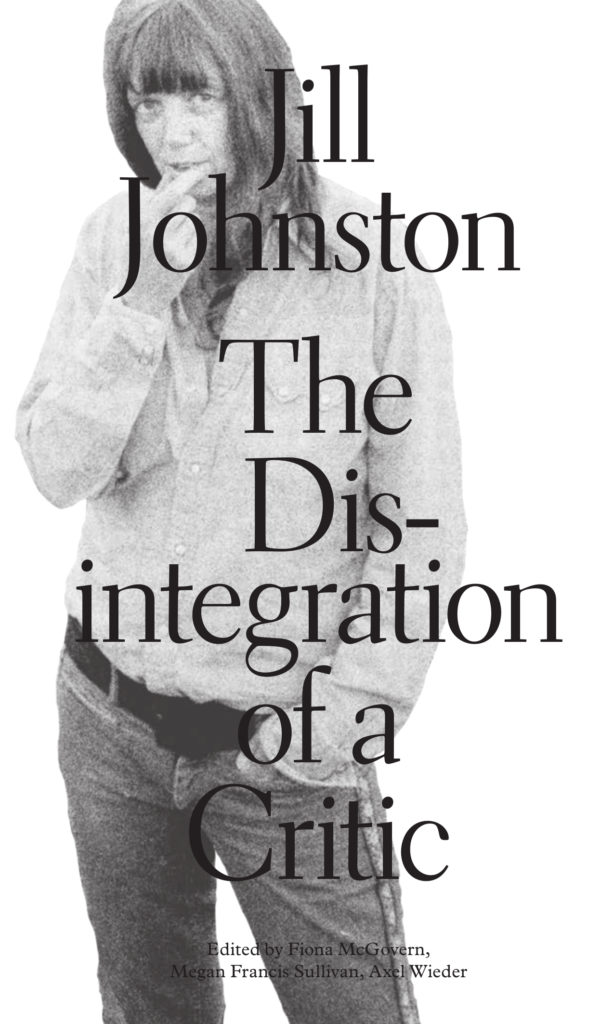

“She writes like a Film,” said Andy Warhol, describing Jill Johnston. The self-anointed prince of the New York underground art scene joined a star-studded panel including Ultra Violet and Carolee Schneemann in May of 1969 to discuss “The Disintegration of a Critic: An Analysis of Jill Johnston” at the Loeb Center at New York University. This moment—the height of Johnston’s career as an all-encompassing cultural critic for the Village Voice—is the jumping-off point for the editors of a new volume of Johnston’s collected writings, Fiona McGovern, Megan Francis Sullivan and Axel Wieder, along with contributors Ingrid Nyeboe, Bruce Hainley and Jennifer Krasinski, to revisit the legendary critic’s writings and social context.

In the years since 1969, Johnston has been best known—and forgotten—as a lesbian icon and provocateur. Her reputation is spread by second-hand stories of her outrageous behaviour, including simulating a lesbian threesome during a 1971 public panel as a response to Norman Mailer’s chauvinism and skinny-dipping in the middle of a Women for Equality talk on a private estate in the East Hamptons. A record of these exploits, Johnston’s weekly columns from 1960 to 1974, has been edited down to summon a singular and often erratic voice that was unfailingly human in its critical curiosity. Johnston’s first-person-autobiographical columns marched step by step with the innovations of Fluxus, Merce Cunningham and the Judson Dance Theater. In the early days of live art, before the proliferation of image-based documentation, artists like Yvonne Rainer and Steve Paxton especially relied on verbose interlocutors like Johnston to progenate their art into the rest of the world.

Organized chronologically, the volume traces Johnston’s “disintegration” as she takes the scenic route through the 1960s New York art scene with shenanigans she herself catalogued in texts such as “Bash In the Sculls” (1970) and “Lady MacBeth with a Rubber Dagger” (1973). Anticipating New Narrative writing, Johnston, sensing either boredom or breakdown, continuously evaded genre, category and authority at every turn. Over the course of her generative columns, readers see her shift from an astute and sensitive dance critic to an outlandish poet and personality who documented her life as she moved through the worlds of art and feminism. This collection extends briefly into Johnston’s separatist lesbian writings to include her desert pilgrimage to Agnes Martin, which, in my mind, marks the beginning and not the end of the majority of Johnston’s oeuvre. But as the unpopularity of second-wave feminism and lesbianism reigns, this collection carefully focuses on her earlier writings in and around art, as if art and politics could live separately in remembering Johnston.

Devoting a considerable page count to the 1969 event that lends the collection its name, and at times resembling a shrine-like celebration of a complicated body of work, this collection in the end doesn’t make me yearn for more Jill Johnston; rather, I feel a deeper sorrow for the loss of publications like the Village Voice. Only an alternative local media platform could have supported and sustained a free-rein columnist like Johnston, and in turn generated such an enriched discourse that relied on devoted public readership. In an age where weeklies and independent media outlets are dropping by fistfuls and all art publications look and sound the same, Jill Johnston: The Disintegration of a Critic hearkens to a past that feels so familiar, yet increasingly impossible to imagine.