Jérôme Nadeau’s second solo exhibition in Montreal, “Poor Healer,” is one of intuitive exploration and multitude traces. It’s an invitation to get lost in a maze, to get trapped in a web. Nadeau’s photographic work lies at the intersection of David Cronenberg’s Videodrome aesthetic, death metal iconography and hacker culture of the 1990s. Cultivating a fascination for the screen—its demands, its hyperreality and its destruction—these photos suggest the symbiosis of the organic body and technology.

Nadeau’s works are successively constructed and deconstructed in a handmade process that, with a nod to Walter Benjamin, Gilles Deleuze and Jean Baudrillard, restores the authenticity or singularity of the photographic image. He accumulates image sources, layers, alterations and hours spent in the obscurity of the darkroom where machines—the photo enlarger, for instance—have been tweaked. Meanwhile, repetitions and additions have conditioned the artist’s gestures; mistakes have been made and kept as reminiscences. Moiré effects add a level of interference that is at once captivating and disturbing, recalling the difficult task of taking a picture of either a television or a computer. Anything usually considered a threat to the photographic process itself—dust, scratches, light or the absence thereof—becomes another compositional source for Nadeau, returning to the material essence of the image while deepening its perceptual static.

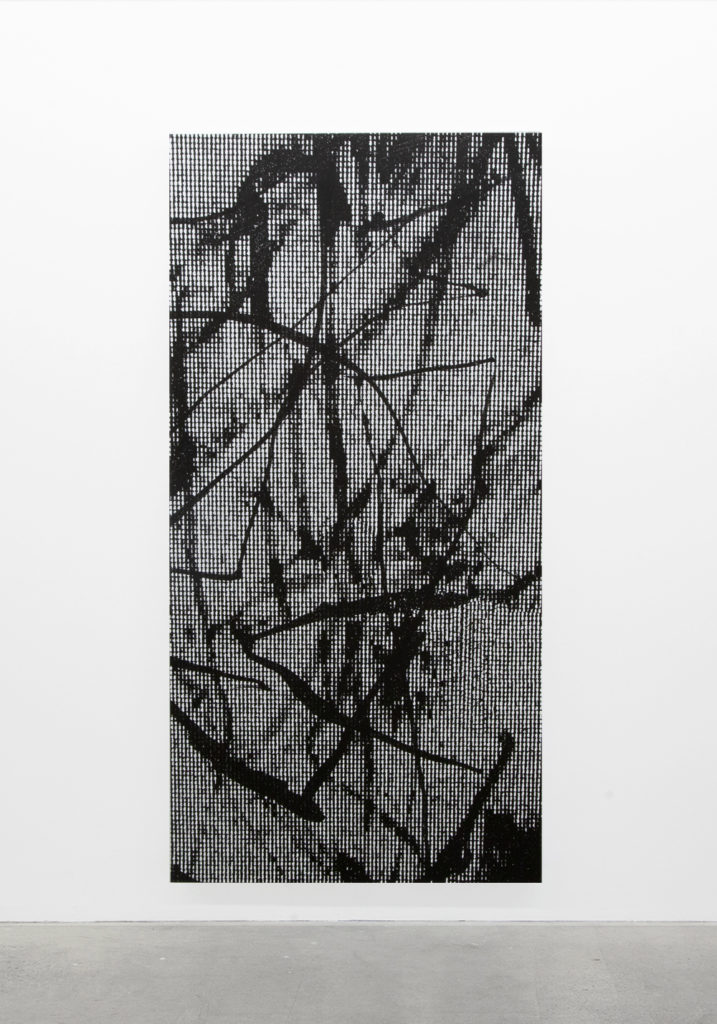

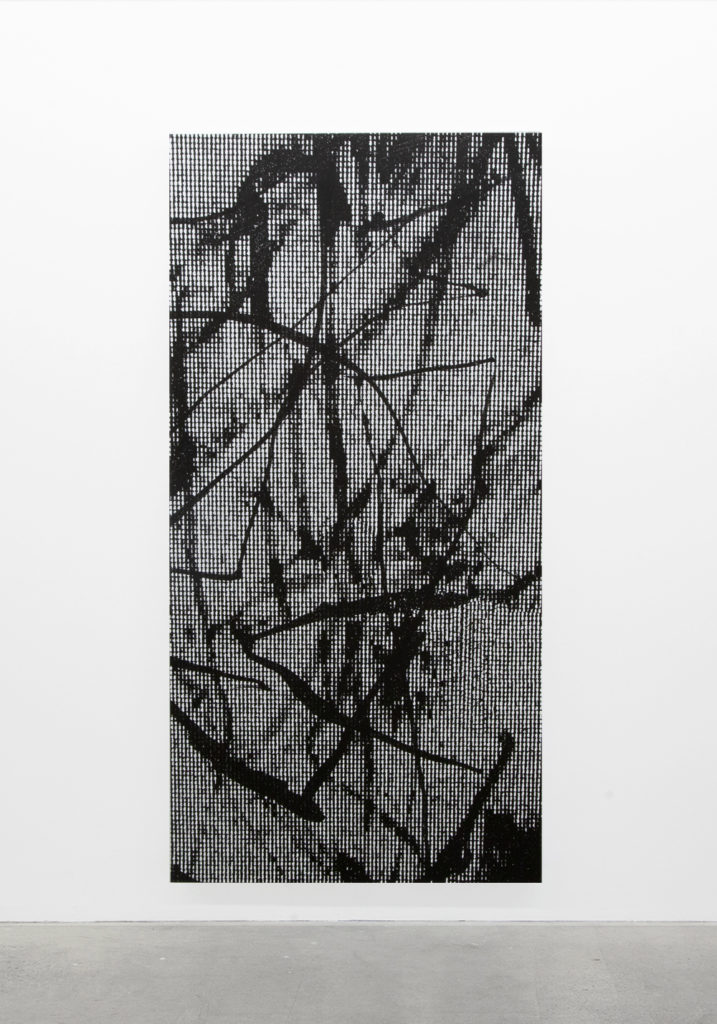

In this alternative reality, each image tells its own story through endless visual interconnections and narrative juxtapositions that generate a meaning of their own. Four large-scale photographs suggest portals to a parallel universe, mirroring the screen through which one browses the internet. This hyperlinked, networked structure is apparent in SLUGG139 (2019), in which multiple branches spread freely in every direction without any central core, and in The Crawler (2019), where the presence of recurring patterns, comparable to ramified roots, echoes the shape of a spider. The central piece, an untitled Renaissance-esque portrait of a young woman emerging from a gloomy background, gives a glimpse of a delicate face with diaphanous skin. Here, textures act as trompe l’oeil: as the viewer approaches the work, the image becomes increasingly pixelated and unresolved. Whatever the provenance of the original image, long lost in Nadeau’s incessantly layered and hypertextual production, is impossible to recollect. Its silhouette stands as an enigmatic spectre.

In Iris Twice & Narcissus (2019) and Shelters (2019), two of Nadeau’s small-scale works in the exhibition, surface scratches echo Ernest J. Bellocq’s early 20th-century portraits of red-light district filles de joie, with subjects’ faces scratched off to protect their anonymity. Nadeau’s marks, however, are antagonistically innocent and self-aware, primed with juvenile violence and guilty pleasure. They remind us of the delinquent act of engraving one’s name in the bark of a tree or spray-painting graffiti on the metro. Drastically contrasting with the imposing works, these inconspicuous photographs present themselves as thoroughly manipulated objects. Gestures of the hand are made visible, conceding a strong material aspect to the photographic process itself, a practice that is by definition mediated and generated by an apparatus.

As Nadeau gleans myriad images, diving deeper into the abyssal and fathomless chasm of the internet, his quest is endless. Here, Nadeau narrowed down a selection of works from a wider corpus; a constellation of photographs to choose from, to combine and assemble. There’s something intriguing, elusive and seductive in “Poor Healer”—a surface yet to rip in order to traverse to another dimension and finally get off the grid.

Jérôme Nadeau, SLUGG139, 2019. Ink-jet on canvas, 1.52 m x 101.6 cm.

Jérôme Nadeau, The Crawler, 2019. Ink-jet on canvas. 1.52 m x 101.6 cm.

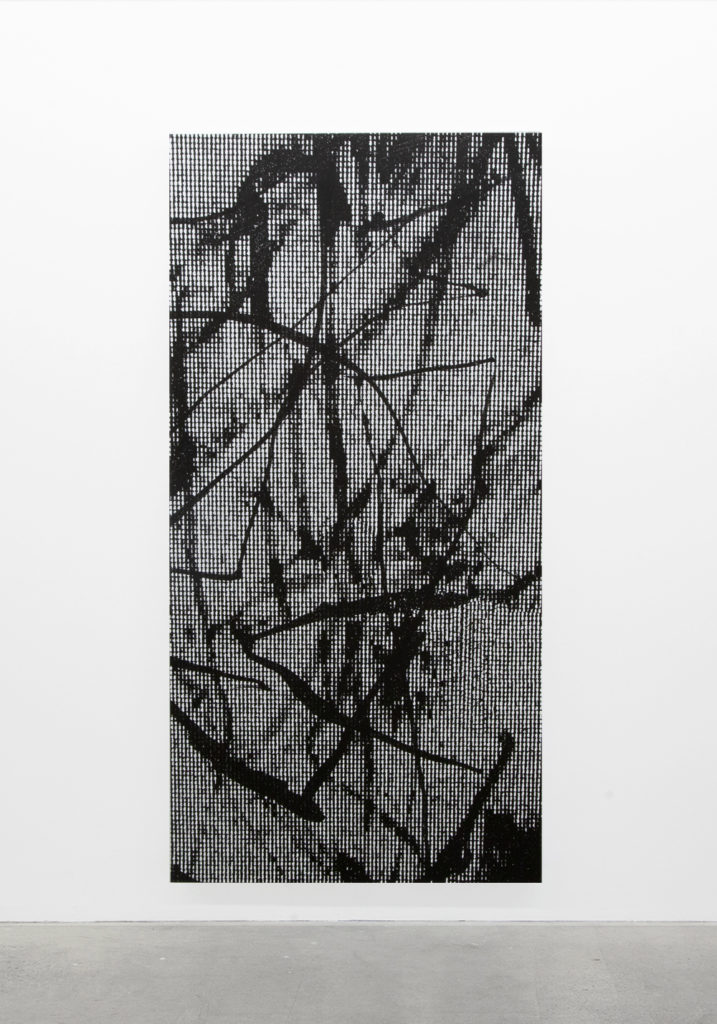

Jérôme Nadeau, Less Lost, 2019. Ink-jet on canvas, 1.52 m x 101.6 cm.