Can an art gallery truly serve a community? Can it temporarily fill in for communal spaces missing within a city, a region or beyond? If so, what would that look like?

Some artists in Halifax have been attempting to answer these questions, using gallery spaces to serve their communities and opening discussions over why such spaces are not already present. Recently, Mario Doucette, Stephanie Wu, and the group behind “Kepe’kek from the Narrows of the Great Harbour” have each claimed territory in their respective projects, carving out a place their art can be seen and their truths heard.

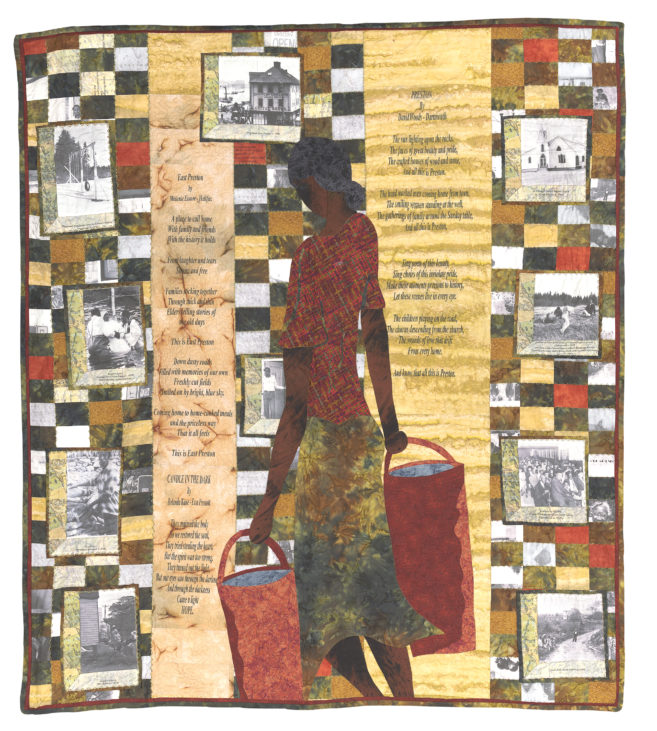

Mario Doucette’s “Dispersions”, the Acadian artist’s recent exhibition at the Anna Leonowens Gallery, presented a new historical perspective on Atlantic Canada’s colonial past. His works ask viewers to re-examine major figures, bringing to light the falseness of long-held narratives. Doucette’s work can be seen taking up arms against the one-sided history of the Acadians in Atlantic Canada—a history, as he points out, written from the colonial British viewpoint.

In his oil paintings and coloured-pencil drawings, Doucette retells historical meetings, events and colonial actions taken by the British against the Acadian and Indigenous populations in Atlantic Canada. In the gallery, two facing walls held images that depicted meetings between prominent Acadian figures dressed in togas and British colonizers in contemporary military and formal wear. On a third gallery wall, 17 drawings and one oil painting on paper crowded each other, offering related retellings.

Doucette’s work demands recognition of truth; it sheds light on the incomplete narratives we have fostered and continue to foster in Halifax and across the Atlantic region. Mario Doucette created an Acadian space in his exhibition, a space in which voices that have been long ignored and misrepresented are commanding and entitled to their histories.

An image of paintings by Mario Doucette on view at the Anna Leonowens Gallery this fall. Photo: via Anna Leonowens Gallery.

An image of paintings by Mario Doucette on view at the Anna Leonowens Gallery this fall. Photo: via Anna Leonowens Gallery.

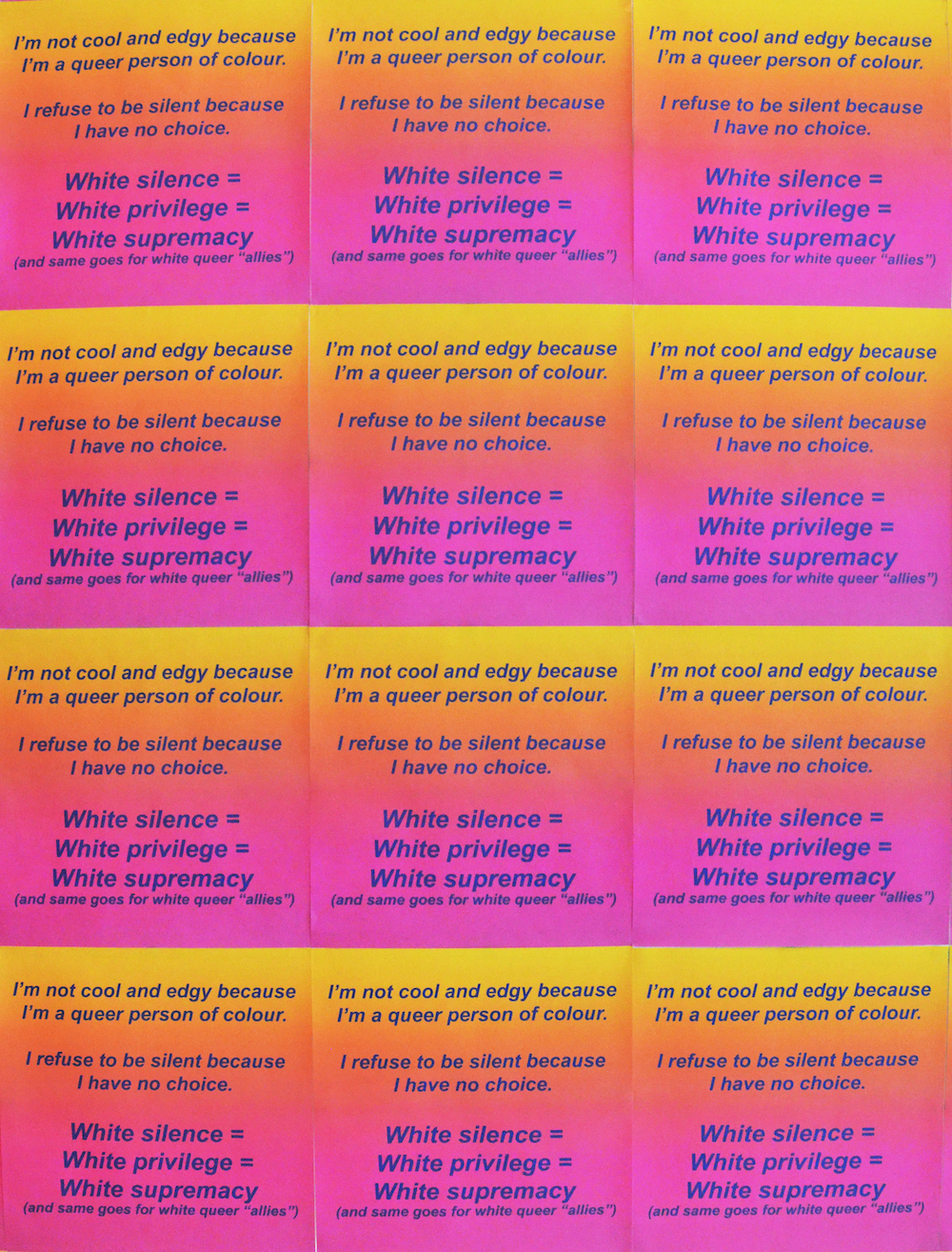

Nearby in the Khyber Centre for the Arts, Chinese Canadian artist Stephanie Wu culminated their residency with “We Met Online: Finding Each Other.” This video and sculpture-based exhibition examined and exposed the lack of intersectional queer and trans spaces in Halifax (and, by extension, throughout Westernized queer culture) through use of posters, installations and GIFs.

Wu’s art points out the hypocrisy many white allies exhibit by continuing to perpetuate and engage in a culture that excludes many people of colour, especially on issues of queer identity and mental health. Wu covered one wall at the Khyber with posters reading “I’m not cool and edgy because I’m a queer person of colour. I refuse to be silent because I have no choice. White silence = White privilege = White supremacy (and same goes for white queer “allies”)”. A giant pair of white arm’s-length gloves, Wu’s White Ally Gloves, hung from the ceiling, blocking the view of the wall slightly.

Beside the posters, two projections played on loop—GIFs Wu made pointing out struggles with online dating, finding communities, mental health and identity.

Due to exclusion, many queer/trans people of colour turn to the Internet, a fact stated by Wu in their artist bio for this project, in search of community and to find a place of belonging. Wu creates this space in their exhibition through memes and installation, inviting those in the QTBIPOC community to see their experiences reflected and to engage in a critique of white queer culture.

A view of some of the posters in Stephanie Wu’s project We Met Online: Finding Each Other. Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

A view of some of the posters in Stephanie Wu’s project We Met Online: Finding Each Other. Photo: Courtesy of the artist.

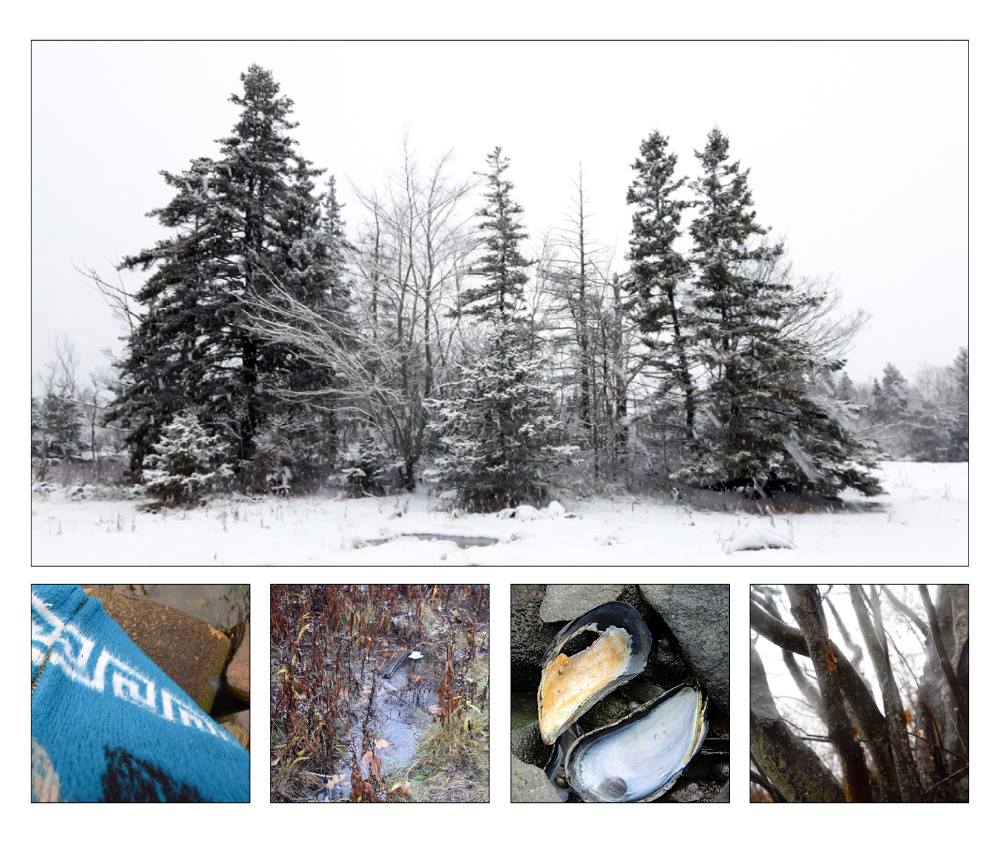

Currently running at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia (where, full disclosure, I am currently a curatorial intern), “Kepe’kek from the Narrows of the Great Harbour” marks the 100th anniversary of the Halifax Explosion by commemorating an early Mi’kmaq settlement, Turtle Grove, which was destroyed in the explosion but that is rarely mentioned in its official histories.

“Kepe’kek from the Narrows of the Great Harbour” is a collaborative photo-based exhibition that is part of Photopolis, a Halifax photography festival held every three years. The collaboration features five young members of the Mi’kmaq nation—Aiden Gillis, Brandy Bernard, Kehisha Wilmot, Sabrina DiMattia and William Johnson—who worked with youth mentor Killa Mitchell-Atencio and photo mentor Hannah Minzloff, as well as others, over a year to make this exhibition.

“Kepe’kek” walks you through how the artists engaged with the space the settlement sat on, the history of the community, and their cultural heritage. By incorporating traditional beading practices, written works and other mediums, the artists invite the viewer into their experience with Turtle Grove.

What “Kepe’kek” also does is explore a history that was overshadowed and cast aside. The work within the exhibition records the loss that was experienced in Turtle Grove while offering a form of remembrance and recognition.

Each artist is given a stretch of space to show their photography along with other works, including paintings, drawings and sculptures. One wall displays beadwork by Kehisha Wilmot overlapping with photos of leaves and the ground, while another wall presents oil paintings by Aiden Gillis of animals found in the area. A wooden sculpture, done by William Johnson, sits in front of an installation of his Facebook posts discussing Mi’kmaq sovereignty and history.

Images from the exhibition “Kepe’kek from the Narrows of the Great Harbour.” Top photo: William Johnson. Bottom row left to right: Aiden Gillis, Kehisha Wilmot, Sabrina Di Mattia, Brandy Bernard. Photo via Photopolis Facebook page.

Images from the exhibition “Kepe’kek from the Narrows of the Great Harbour.” Top photo: William Johnson. Bottom row left to right: Aiden Gillis, Kehisha Wilmot, Sabrina Di Mattia, Brandy Bernard. Photo via Photopolis Facebook page.

The artists behind “Kepe’kek from the Narrows of the Great Harbour”, like Wu and Doucette, have shaped a space for their own histories and truths to be on display. All three shows are highly personal, and this is viscerally felt, as each exhibition has evoked an insistent need for place and recognition.

Working to assert their own identities and communities, so often left out of the overarching popular narrative, these artists redefine and fill their gallery spaces—whether that be by satirizing historical retellings of Atlantic Canadian colonization, by broadening the inclusivity of queer communities, or by paying homage to overlooked Indigenous experiences. In this way, the galleries themselves are transformed to encompass something greater.

As viewers, we are gifted with the ability to move through these types of exhibitions and witness them becoming—even temporarily—communal spaces for healing, belonging and inclusion.

Emma Steen is currently finishing her degree in art history with a focus on Indigenous art histories and visual culture at NSCAD University. She is also currently taking part in a curatorial internship at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.