Halifax is a place of coming and going. It is a student city, a naval hub and a port city—meaning many pass through only forming shallow roots here. This is true of established artists who visited NSCAD in the era known locally as the “golden years” (that is, in the late ’60s and early ’70s). Due to its proximity to New York City and its geographic isolation from major press outlets, Halifax became a centre for artistic experimentation, free from the imposing gaze of the art critic.

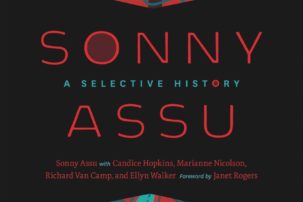

A recent visit from New York– and Toronto-based artist Brendan Fernandes marked the historic reopening of the NSCAD Lithography Workshop, known for having hosted artists such as John Baldessari and Sol LeWitt in the “golden years.” More than 35 years after it hosted its last visiting artist, the Lithography Workshop has been reinvigorated though the efforts of the Anna Leonowens Gallery, which of late applied for, and received, Canada Council New Chapter funding to revitalize the project. An ambitious roster of eight high-calibre artists has been assembled to visit in the next few years, including Kwakwaka’wakw artist Sonny Assu and Toronto-based artist Ed Pien, both of whom work primarily outside of traditional printmaking.

Brendan Fernandes (right) in the NSCAD Lithography Workshop with Ryan Josey (middle)—his studio manager and contributing writer for Still Move—and master printer Jill Graham (left).

Brendan Fernandes (right) in the NSCAD Lithography Workshop with Ryan Josey (middle)—his studio manager and contributing writer for Still Move—and master printer Jill Graham (left).

The Fernandes visit coincided with the Halifax launch of his book Still Move, and his exhibition “Move in Place” at the Anna Leonowens Gallery. The exhibition featured a selection of digital prints which show elegant dancer’s limbs protruding from objects kept in museum collections of African art. In this way, Fernandes reintroduces dance gestures to objects which were historically stripped from dancing bodies. He highlights the intersecting colonial legacies of museology and ballet, demonstrating how they both operate as masquerade.

The thin digital prints lining the walls left the gallery empty, almost as though leaving room for the next leg of the project. In collaboration with Tamarind-certified master printer Jill Graham, Fernandes is developing a body of work using silhouettes of dancing bodies, tessellated in a rhythmic formation. Like “Move in Place,” this upcoming project acknowledges the history of ballet and the pain that is hidden by dancers. Upon closer examination, dancers in second position in the Fernandes prints, limbs slightly spread in a loose starfish, resemble chalk outlines, and it becomes difficult to hear the word arabesque without considering the colonial root of its name.

Lisa Steele and Kim Tomczak, still from Becoming…, 2006–2011.

Lisa Steele and Kim Tomczak, still from Becoming…, 2006–2011.

I often hear it said that you must leave in order to stay in Halifax, and it is true that many artists must seek artistic validation in larger centres before succeeding in the small city. Two university art galleries are currently showing touring exhibitions of artists who have spent time in the city briefly and are creating work between cities, experiencing success in and out of the Atlantic.

“The Long Time: 21st Century Art of Steele + Tomczak,” curated by Paul Wong and circulated by On Main in Vancouver, is currently on view at Dalhousie Art Gallery, closing July 16. The collaborative duo and co-founders of Vtape have spent time in Halifax expanding upon certain bodies of work, ones they have restaged in various cities.

In 2014, for instance, Steele and Tomczak recorded the fears and aspirations of local students for their portrait series …bump in the night, which is on view at Dal and documents the commonalities among urban youth from differing geographic regions. Halifax also joins the list of cities featured in the video installation Becoming…, in which the artists meet a city by recording how it reveals itself to them. Using primarily video and lens-based media, the duo refers to video as “our best mirroring device,” disclosing what’s already there.

Brenda Francis Pelkey, Court, Cobourg, 2005. Printed large format 2016. Inkjet on bonded aluminum. 1016 x 165 cm. Collection of the artist.

Brenda Francis Pelkey, Court, Cobourg, 2005. Printed large format 2016. Inkjet on bonded aluminum. 1016 x 165 cm. Collection of the artist.

“Brenda Francis Pelkey: A Retrospective” was recently on view at Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery, toured by the Art Gallery of Windsor. On the cusp of the ’90s, Francis Pelkey became known for her photographs using cinematic lighting and Cibachrome processes to document rural-backyard paradises.

Capturing domestic havens populated by trinkets and lawn ornaments, Francis Pelkey highlights the ways that citizens seek refuge in isolated communities. Memento Mori (1993–97) and dreams of life and death (1991–94) are bodies of work that reflect the artist’s experiences in her childhood home of Havre Boucher, Nova Scotia, and in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Her nightscape photography evokes a stillness that is both quiet and rattling, and accompanying texts recount traumatic incidents which, in the artist’s words, “burn themselves into memory.” Despite the incidents having occurred in Nova Scotia and the photographs having been taken in Saskatchewan, the memories stretch across the artist’s common experiences in both places.

Installation view of “The De-Celebration of Canada 150” by Raven Davis, on view at Khyber Centre for the Arts.

Installation view of “The De-Celebration of Canada 150” by Raven Davis, on view at Khyber Centre for the Arts.

An artist based in two cities, Raven Davis has been travelling between K’jipuktuk (Halifax) and Tkaronto while building towards “The De-Celebration of Canada 150.” During the Mayworks festival in the spring, the Anishinaabe artist staged a series of performative interventions in public spaces under this title, and Davis recently mounted an exhibition by the same name at Khyber Centre for the Arts in Halifax, on until July 15.

Simply put, the exhibition is fist-forward. Calling Canadian propaganda on its genocidal legacy, Davis takes a blunt stance in an art world that often praises nuance. One wall is papered with Canadian Tire money edited to say “Indians are Tired” and the opposite wall bears an all-white Canadian flag overlaid with a projected video of a rotating Mountie figurine. Elsewhere in the gallery, that same worn-down figurine (revealed to be a whiskey decanter and a music box) is presented on a plinth under the title Genocide Enforcer. The exhibition turns colonial spectacle on its head, and it repurposes the symbols of Canadian nationalism to expose their bloody past and present.

Billy Gauthier, Song from the Spirit World, n.d. Caribou, moose antler, serpentinite, 38.1 x 33 x 17.8 cm. Collection of Grenfell Campus, Memorial University. On view in “SaKkijâjuk’ at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

Billy Gauthier, Song from the Spirit World, n.d. Caribou, moose antler, serpentinite, 38.1 x 33 x 17.8 cm. Collection of Grenfell Campus, Memorial University. On view in “SaKkijâjuk’ at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

Until September 10, the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia is the second stop for “SaKkijâjuk,” a touring exhibition of Inuit art from Labrador which originated at the Rooms in St. John’s. The tour is meaningful in itself, since a major transdisciplinary survey of artwork from Nunatsiavut has never left the province to circulate nationally. With the exception of an exhibition of grassworks which toured the Eastern Seaboard in 1981, there has been little opportunity for artists from Nunatsiavut to exhibit their work outside of their communities.

“SaKkijâjuk” hinges on the year 1949—when Newfoundland and Labrador joined Confederation, and when James Houston took measures to establish an Inuit art market in the south. The Terms of Union for the province’s accession made no mention of Inuit, Innu or Mi’kmaq peoples living in Newfoundland and Labrador, ultimately rendering Indigenous peoples in the province invisible to federal authorities, and therefore ineligible for federal services. Meanwhile, that same year, a sold-out Montreal exhibition of Inuit art at the Canadian Handicrafts Guild, organized by Houston, created a spike in demand for art from the north. As James Houston was forging trade routes to bring Inuit art from the north to southern exhibitors and collectors, Inuit artists in Labrador were being systematically shielded from the national public’s gaze.

“SaKkijâjuk” means “to be visible” in the dialect of Inuktitut spoken in Labrador, and the exhibition celebrates many regionally specific practices of the southernmost Inuit communities. In her curator’s talk, Heather Igloliorte acknowledged that Inuit art is incredibly market-driven, making it difficult for artists to address histories of trauma that aren’t palatable to commercial audiences. “SaKkijâjuk” provides an opportunity for photographers, carvers, illustrators and artists across four generations to exert cultural sovereignty over their own histories. The exhibition is slated to visit the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 2018, coming and going through communities and across territories in the coming years.

Halifax can serve as a gathering place for visitors, and an incubator for new projects. As touring exhibitions and visiting artists move through the city with increasing frequency, institutions are called to consider what it means to be a good host.

Amanda Shore is a freelance writer and curator based in Halifax.

Brendan Fernandes, Move in Place, 2015. Digital C-print, 76.2 x 76.2 cm. African art images courtesy of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, the Justin and Elisabeth Lang Collection of African Art.

Brendan Fernandes, Move in Place, 2015. Digital C-print, 76.2 x 76.2 cm. African art images courtesy of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, the Justin and Elisabeth Lang Collection of African Art.