HaeAhn shows me a huge half-healed rash running up her leg, the result of touching uncured ottchil lacquer with her bare hands. This material is central to the recent exhibition “maximum suffering along the way,” by HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander, which is the collaborative practice of HaeAhn Kwon and Paul Kajander (HPKK). Ottchil lacquer is made with the sap of the lacquer tree, and contains the same chemical substance as poison ivy. Upon contact, the resulting dermatitis looks like a blistered and peeling scab, wet and dry—and itchy, the itchiest of itches. HaeAhn’s agitated skin suggested a painful trespass between worlds, between inside and out, and reminded me that the body’s provisional scaffolding of a thickened porous scab manifests itself to seal that trespass. At the same time, itchiness tempts us to scratch and re-open the small hole into ourselves. Unlike a physical wound, the origin of a rash can be hard to trace, shifting an outbreak across the body’s surface, this time from hand to leg. The body is like a river, where injury and illness flow through its invisible streams, liquid inside and air outside. And in South Korea—where the works in the show were produced over three summer months—the fifth cardinal direction is inward.

The first work one encountered was, appropriately, a sort of doorbell: a small brown plastic wall-plate with a funky cubic relief surface, a broken springed button and adorned with the iridescent wing-cover of a beetle, mistaken for a lost acrylic fingernail. Further into the gallery were two framed images scanned from a from a 1975 propagandist publication, printed to commemorate the 30th anniversary of national liberation from Japanese occupation. One image, a black-and-white photo of a happy family in the front yard of their Western-style bungalow, was used to promote a modern South Korea. HPKK tell me that this style of private home was only for the super-wealthy, and nowadays the dream is to perch above the smog in a glass-wrapped condo—although the windows don’t open, but there’s AC for that. Another framed image shows a cardboard shipping box spilling bolts of plaid cloth, like rays of sunshine, over a painted globe, turned to show the North American continent. And above, a page torn right out of the same propo-pub hangs limp from the overhead fluorescents, with advertisements for Korean rubber and a picture of an industrial factory landscape. I’m reminded that fluorescent-tube gallery lighting is also industrial lighting, the kind that makes a windowless machinist shop into a 24-hour workstation of shadowless daylight. It was in a warren of such workshops that several of the exhibition’s smaller sculptural pieces were produced: a tiny stone “delete” key sits on a custom shelf, an aluminum framed mount is wedged low in a corner, and hanging on the wall is a mesh wire basket/cage painted the orange of Seoul’s taxis.

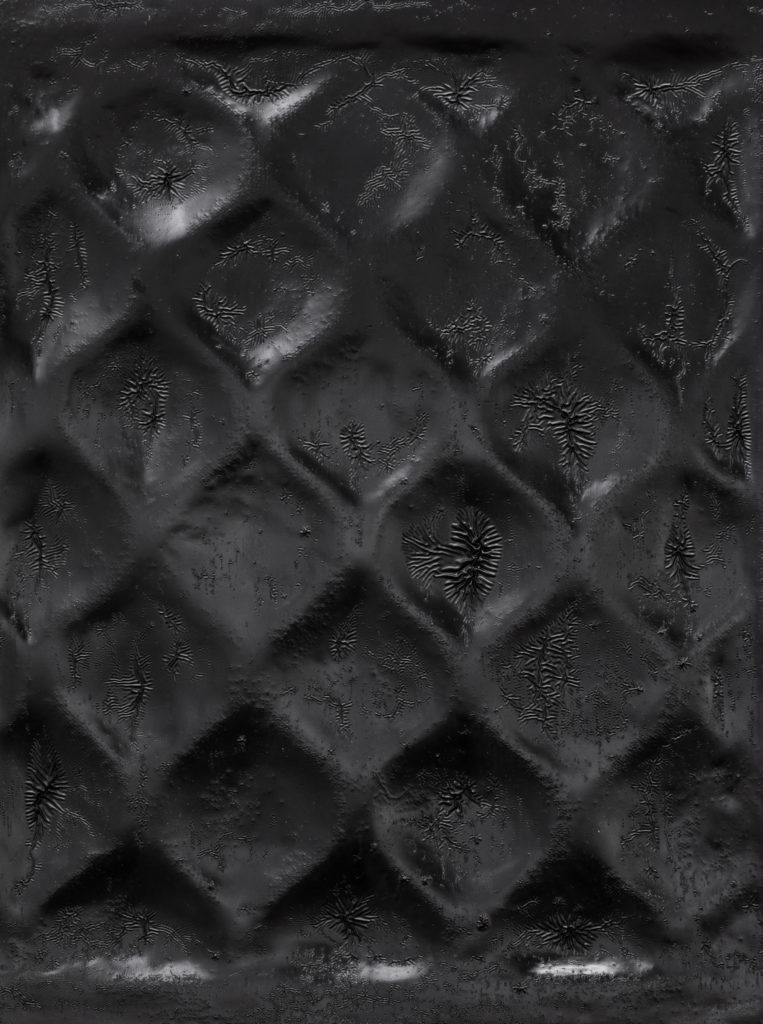

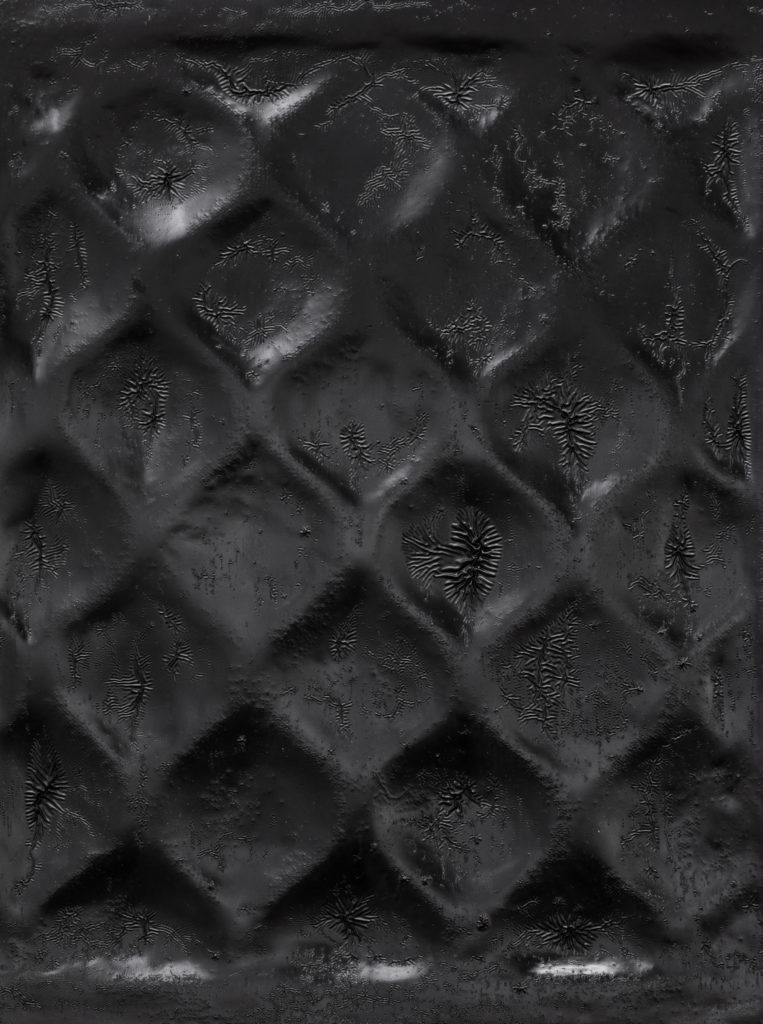

HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander, Supervisor, 2019. Lacquer, glutinous rice powder, textiles, ash powder. Courtesy Franz Kaka.

HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander, What’s Going Down Keeps Coming Up (detail), 2019. Courtesy Franz Kaka.

HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander, Trot Rubber, 2019. Lacquer, magazine pages. Courtesy Franz Kaka.

HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander, It Fits (Center Outside), 2019. Door-bell from abandoned Gaeryang Hanok, sea-shell, beetle. Courtesy Franz Kaka.

HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander, ,Plaid Obscene, 2019. Framed archival print, powder-coated steel. Courtesy Franz Kaka.

All of these objects were made in Euljiro, a neighborhood in Seoul where more than 10,000 machinist shops are huddled together in a tight maze of narrow passages. Because each shop has its own speciality, machinists work in collaboration with other machinists, who have other machines, skills and tools. Complex jobs are problem-solved collectively. The maker of the wire basket led HPKK through the warren, down unmarked halls and alleys to the shop of the person who could paint the metal orange. Euljiro is an ecosystem that can build almost anything, relying on relationships and the map-like memories of those who inhabit it. Euljiro is also one of the last areas near Cheonggyecheon River that hasn’t been demolished and redeveloped. Soon enough, the machinists and craftspeople are likely to be pushed out from the centre, dispersed into liminal factory zones, into assembly lines and deskilled wage-work.

For hundreds of years, ottchil has been used to make religious statuary: life-size gold leaf–plated and painted Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. In the dry-lacquer technique, tree sap is combined with ash, glutinous rice powder, clay powder and linen, which is applied in many thin layers over an armature, such as a clay or wood model. With time, heat and humidity, it polymerizes into a glassy-smooth and hard black substance, which is then cut and peeled from the armature to produce a hollow lacquer shell. Unlike most materials, ottchil lacquer will not rot or rust from the monsoon’s wilting heat and heavy rain, and the lightweight statuary could be easily transported from the workshop to the temple.

The armatures for HPKK’s ottchil works were not Buddhas but the steel, geometric grids of burglar bars, sewage grates and other infrastructural objects made and found in Seoul. They are the accessories of private property, which perform a cautious porosity between a chaotic outside and an ordered interior. Using skills gained through an informal apprenticeship, HPKK applied the lacquer onto the steel armatures, layered with the traditional linen cloth used for making statuary. This same cloth, also used for baby diapers and funerary clothing, ties together the most essential of human creations: babies, shit, corpses and gods.

Ottchil is a temperamental material, requiring patience and skill, along with the right curing conditions. HPKK’s experimentation, combined with a lack of expertise, resulted in surfaces that were not as glassy-smooth as they should be. They instead appear uncured, as if stuck in a sticky interstate of semi-fluid flux. Like a wound on its way to becoming a scab, they closely parallel the outbreaks on their own skins. On the back gallery wall is the fifth lacquer piece; its ottchil is the colour and texture of frothing blood. Cast from a notched brick, it rests on the custom steel shelf, paper-weighting a few Euljiro business cards. Inlaid into its bubbling skin-flesh are delicate opalescent shells cut into the shapes of an industrial excavator, disassembled to abstraction.

How did the image of idealized Western cities become so pervasive, to be transplanted almost identically across the globe? Like the seeds of an aggressive invasive species carried on the breeze, it will corrupt where it lands. But this species has no natural ecosystem. It is an ideal with no basis in the realities of city life; it’s a glossy image torn from a magazine. Centreless, anarchic symbiosis, such as that found in Euljiro, is what the modern city devours, and the glass facades of newly stratified, subordinated zones conceal the empty promise of modernity. This dreamed-of city bears no fingerprints, and shines like an empty mirror.

HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander’s use of ottchill engages the ecosystematic history of craftspeople in Seoul, while allowing them to self-reflexively question their own acts of making and living. In their new home, Toronto, the vernacular and modernized city are similarly at odds with each other. While the modernized city is akin to the violent grafting of an artificial skin—one which is smooth but does not feel—the vernacular city is an unhealing wound, forever in an incomplete process of transformation. It is an inimitable and perpetual congealing of time and place. Between these two cities, “maximum suffering along the way” gives us a point of contested contact, a puncture through which a breath might pass, a scab to pick.

HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander, Empty Itch (detail), 2019.

HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander, Empty Itch, 2019. Lacquer, glutinous rice powder, textiles, ash powder, over-sized zippers. Courtesy Franz Kaka.

HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander, Jail Needs to Feel Like a Home, 2019. Archival print on paper, acrylic case. Courtesy Franz Kaka.

HaeAhn Paul Kwon Kajander, Jail Needs to Feel Like a Home, 2019. Archival print on paper, acrylic case. Courtesy Franz Kaka.