I was excited by the prospect of Gauguin: Voyage to Tahiti, a film about Paul Gauguin’s time in Tahiti at the end of the 19th century. I had hoped that a 2018 film about a French artist who influenced the modernists would interrogate the colonialist aspects of his legacy, but I was disappointed. Gauguin is just another film about a white European man taming wild islanders on his canvas.

French filmmaker Édouard Deluc freely adapted from Gauguin’s travelogue Noa Noa, first published in 1901, containing reflections and paintings from the artist’s time in Tahiti. Gauguin (Vincent Cassel) leaves his wife, their five children and a life of poverty in France in search of artistic inspiration. On the Polynesian island of Tahiti he marries Tehura (Tuheï Adams), who, ostensibly untamed and chaste, becomes his muse. They create a home in the forest far away from her family, where he paints while she cares for him and learns to speak French.

The film’s narrative meanders around Gauguin as though he is a demigod: his art a religion and he, its prophet. He controls Tehura’s whereabouts to suit his lifestyle and keeps her from her family and friends, whom he finds threatening. She barely speaks, and as the film progresses her facial expression bears loneliness. He makes her pose for him topless and arranges her body according to his artistic vision, though she yearns for a modest white dress and Sundays at church. Gauguin claimed to paint for the sake of Christianity and live for its teachings, but he resisted her wishes. Tehura, like the other characters, remains secondary and underdeveloped relative to Gaugin’s central figure.

Deluc’s film centres Gauguin’s artistic exploits—he rendered Tahiti and its people through his colonial, post-impressionist lens—rather than critique France’s role there as a colonial power. Speaking about the filmmaking process in an interview, Deluc refers to Tahitians as Maori, but Tahitians are Polynesian. This disregard for accuracy is an example of Deluc’s neglect in representing the land and culture that inspired and nurtured Gauguin. And though the landscape is captured beautifully by Pierre Cottereau’s cinematography, Tahiti and its people remain mere backdrop.

Now is the time for European countries with long and ongoing colonial histories to reflect on their past through art and film. Gauguin, however, is a film that tries to restore the supposed glory of an old white man who sorely lost his way, and I don’t want to see any more of those stories.

Gauguin: Voyage to Tahiti opened in select theatres across Canada in July 2018.

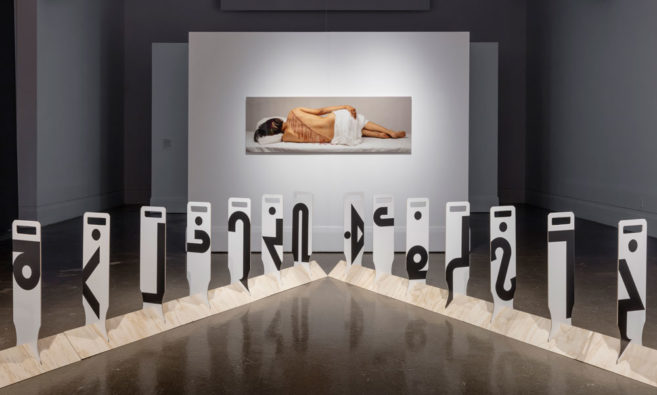

Actors Tuheï Adams and Vincent Cassel in a still from Gauguin: Voyage to Tahiti (2017) directed by Edouard Deluc.

Actors Tuheï Adams and Vincent Cassel in a still from Gauguin: Voyage to Tahiti (2017) directed by Edouard Deluc.