One of the more notable things about Eva and Franco Mattes’s recent exhibition at Phi Foundation for Contemporary Art is what it didn’t include. The Italian-born duo, currently based in New York, are among the pioneers of first-wave Net art and have been active since the mid-1990s. Their consistently pranksterish interventions in online culture span nearly the entire life of the World Wide Web. “What Has Been Seen,” however, was not a retrospective: invited curator Erandy Vergara selected works from the last 10 years of the Matteses’ career, situating them firmly in the present.

On the one hand, this deprives the viewer of the opportunity to observe the duo’s development from the inception of internet art to the present. On the other hand, many of their early works are web-based, dependent on outdated technology and somewhat allergic to being presented in the confines of a typical white cube. This focus on the artists’ recent work had the effect of positioning them less as “new media artists” and more simply as contemporary artists with an interest in the internet.

The first artwork viewers encounter is My Generation (2010), a 12-minute-long compilation of found footage of frustrated gamers exploding into violent outbursts as they play, shown on the monitor of a trashed desktop computer on the floor of the gallery’s entryway. Its tone and title present the prototypical computer user as emotionally stunted and socially maladapted. Its abrasive barrage is no doubt hard on the gallery attendants who live with it. Emily’s Video (2012), however, is more troubling by far: it presents a series of viewers’ reactions to an unseen video apparently sourced from the dark web. Its clearly disturbing content prompts reactions of horror and tears from the traumatized onlookers.

Perhaps the most substantial works in the exhibition are three videos from Dark Content, the 2015 series in which CGI narrators give voice to testimony the artists collected by interviewing hundreds of anonymous content moderators, the hidden labour force tasked with removing controversial online content. While the artists are concerned with the internet’s capacity to stoke humanity’s darker impulses and spread disinformation and hate, they seem equally troubled by the lack of accountability within the privately owned public spaces of social media platforms. As the interviews relate, videos, images and comments are removed at the behest of corporate or political interests at the same time as legitimately misleading, violent or obscene content is flagged for deletion, usually by untrained, low-wage workers.

In many ways, the Matteses have not only adapted to changes in the shifting landscapes of art and the internet, they’ve anticipated them. Whereas early internet culture had a distinct penchant for tech-positive utopianism— an ethos that took a hit after the first dot-com boom but reasserted itself at the outset of the social media era—the Matteses’ work has always had a darker, edgier current very much in tune with the vision of certain younger artists, such as Jon Rafman or Ed Atkins, who also focus on the internet’s potential to incubate alienation and deviance. “What Has Been Seen” testifies to the increasingly dystopian way we see the internet as well as to the duo’s own prescience and enduring relevance.

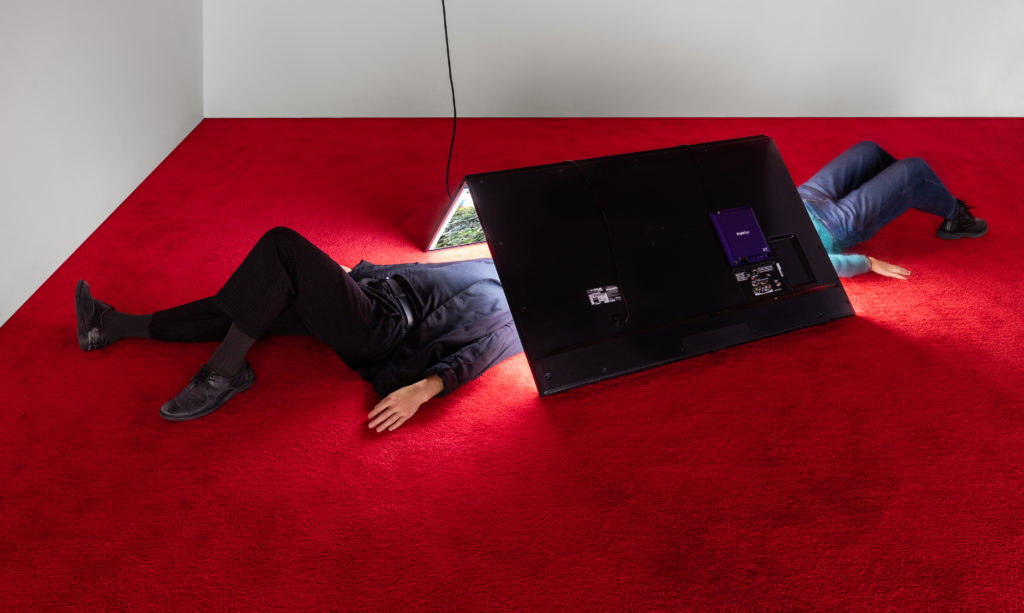

Eva and Franco Mattes, BEFNOED, 2014–ongoing. Videos, screens and custom steel frame, dimensions variable. Courtesy Postmasters Gallery, New York, and Phi Foundation for Contemporary Art. Photo: Melania Dalle Grave for DSL Studio.

Eva and Franco Mattes, BEFNOED, 2014–ongoing. Videos, screens and custom steel frame, dimensions variable. Courtesy Postmasters Gallery, New York, and Phi Foundation for Contemporary Art. Photo: Melania Dalle Grave for DSL Studio.