Tucked away in Winnipeg’s Exchange District, which is filled with historic buildings and local businesses, Urban Shaman presents solely Indigenous artists and has, for the past 23 years, been creating and maintaining a space that prioritizes Indigenous culture and creativity. In “These Tiny Helpers / Agaashiiwi-wiiji’iweg / Ókik ká yá apisísisicik owícihiwéwak,” Dee Barsy’s first solo exhibition, Urban Shaman took on a new, vibrant mode of display: the entire gallery was painted cyan blue—walls, pillars, creaky wooden floorboards and all.

Amid the striking blue, the artist created an immersive experience that reflected her practice of mural painting. Barsy painted directly onto the gallery walls, with large graphics and colourful representations of our insect kin. These insects are native to the territories around Winnipeg and included the monarch butterfly, field cricket, green darner dragonfly, red-belted bumblebee, nine-spotted ladybug, jewel spider, hummingbird clearwing moth, giant water bug and water scorpion. The effect was breathtaking. The site-specific artwork not only represented our relationships to the insect kingdom as Indigenous peoples in so-called Manitoba, but also the interconnectedness between beings on this territory. Against the vibrant blue backdrop—a recurring background colour for Barsy—each insect was painted, its abstracted graphic body floating in relation to the others, weightless and free. It was as though the gallery goer had stepped into the alternate universe of a Manitoba forest, filled with bold circles, lines and rhythmic shapes.

The installation achieved a cohesive representation of our responsibilities as individual entities and suggested how our interconnected roles impact the larger community. Each cylindrical grouping of insects connected to another with an eye-catching line that traversed the gallery walls. These insects, the “tiny helpers” of the title, were attached to each other in many ways; it was the first detail that caught my attention. Such small beings provide prominent teachings for our people, suggesting that hierarchies are obsolete and that we should respect each being as part of knowledge systems that are deeply embedded in the land, the language, the culture and the Creator: Gitchi Manitou.

There was nothing distinctly Indigenous about Barsy’s artworks in terms of traditional style and aesthetics. Rather, Barsy subverts conventional perceptions of Indigeneity by refusing stereotypical iconography that is attributed to Indigenous visual culture, while embracing Indigenous knowledge systems. Urban Shaman, which continues to be an Indigenous-led gallery and platform for artists to expand their practices, supports genuine Indigenous curatorial methodologies and Indigenous cosmologies. By exhibiting in a sovereign Indigenous space, Barsy ensured that her vision and cultural safety were prioritized. Many Indigenous artists are not guaranteed such autonomy when presenting at non-Indigenous institutions that undermine their agency as Indigenous Peoples, whether intentionally or not. Urban Shaman honours ways of living on the land, land that we have protected and prospered on. Getting lost in the striking blue of the gallery took us out of the city, submersing us in the rhythmic representations of our tiny helpers on the ancestral territories of the Anishnaabeg, Cree, Oji-Cree, Dene and Dakota peoples, and the homelands of the Métis nation.

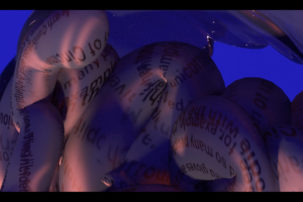

Dee Barsy, installation view of "These Tiny Helpers / Agaashiiwi-wiiji’iweg / Ókik ká yá apisísisicik owícihiwéwak" at Urban Shaman: Contemporary Aboriginal Art Gallery, Winnipeg, 2019.

Dee Barsy, installation view of "These Tiny Helpers / Agaashiiwi-wiiji’iweg / Ókik ká yá apisísisicik owícihiwéwak" at Urban Shaman: Contemporary Aboriginal Art Gallery, Winnipeg, 2019.

Dee Barsy, installation view of "These Tiny Helpers / Agaashiiwi-wiiji’iweg / Ókik ká yá apisísisicik owícihiwéwak" at Urban Shaman: Contemporary Aboriginal Art Gallery, Winnipeg, 2019.

Dee Barsy, installation view of "These Tiny Helpers / Agaashiiwi-wiiji’iweg / Ókik ká yá apisísisicik owícihiwéwak" at Urban Shaman: Contemporary Aboriginal Art Gallery, Winnipeg, 2019.

Dee Barsy, installation view of "These Tiny Helpers / Agaashiiwi-wiiji’iweg / Ókik ká yá apisísisicik owícihiwéwak" at Urban Shaman: Contemporary Aboriginal Art Gallery, Winnipeg, 2019.

Dee Barsy, installation view of "These Tiny Helpers / Agaashiiwi-wiiji’iweg / Ókik ká yá apisísisicik owícihiwéwak" at Urban Shaman: Contemporary Aboriginal Art Gallery, Winnipeg, 2019.