Nickerson’s detailed drawings copy activist street posters: “evict the scum,” “welcome to the art district,” “revitalization = gentrification = rising rents = displacement = class war.” One drawing reproduces a food bank’s hours sign, indicating how restricted access is to this community resource. Another spread illustrates Hamilton as “an urbanist’s utopian fantasy,” complete with “restored Victorian architecture,” “chandeliers,” “DIY art spaces,” “exposed brick,” “counter-cultural consumption,” “lattes,” “vintage fashion,” “Apple products,” “craft beer” and so on. That spread is followed by one illustrating a different reality collecting weekly on the narrator’s lawn: cigarette butts, loans-past-due notices, the ends of food-bank bread loaves, empty medication bottles.

In one of my favourite scenes, the narrator tries to soothe a crying baby in front of a store sign proclaiming, “You can do anything in Hamilton.” Apparently the sign’s creator never had to quiet a colicky child, or steal away from an art event to breastfeed (the latter being another scene depicted in the book).

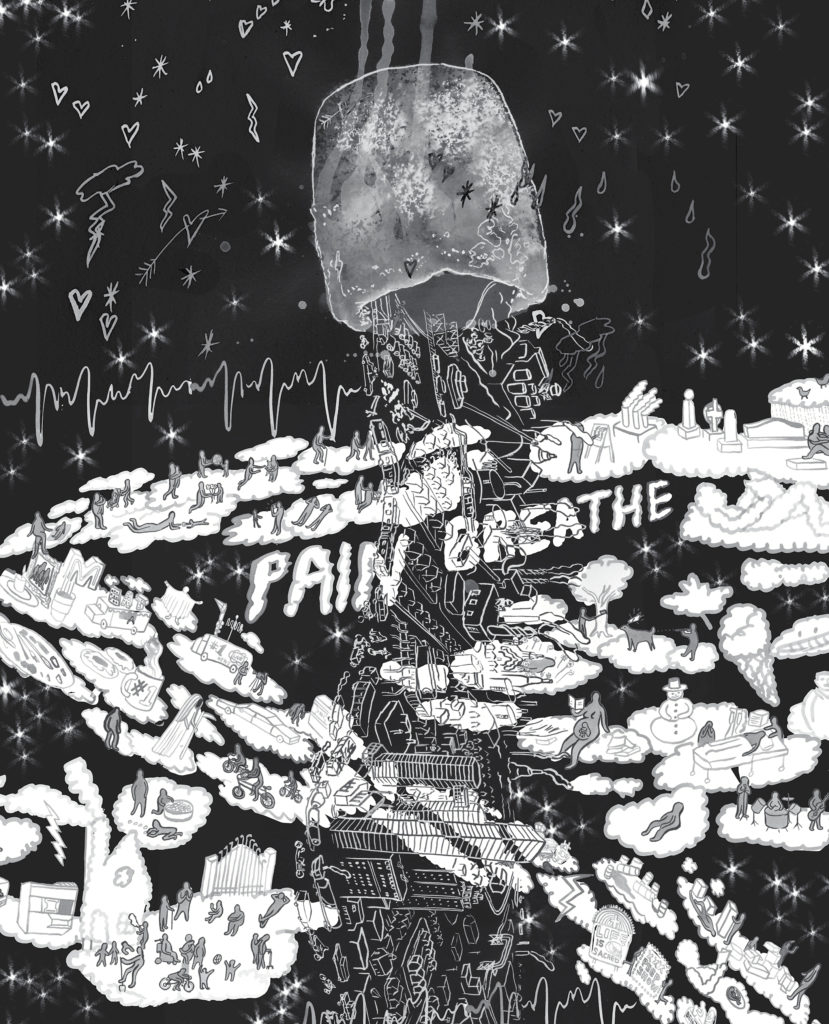

Most of the characters in Creation are rendered as smooth, featureless figures. I read into them exhaustion, dissociation and loss of identity, and the sense of being a ghost unto one’s past self. But keeping visual detail focused on the settings, rather than the actors, adds useful emphasis on the phenomena Nickerson is trying to address, like structural oppression, addiction and poverty.

City landmarks repeat across many pages. This repetition evokes cycles of seeing the same sights every day while also pointing to how a landscape can become a spectre of itself, haunted by dreams and crisis, waterfalls and waste. A shattering of lit and unlit worlds, and a mixing of their shards, is another visual motif. The veil between life and death can be thin when one is the primary caregiver for a vulnerable human being—and the vulnerability of other folks, whether strangers or not, can resonate more intensely then too. “In loving, we give our power away,” observes Creation’s narrator. And power—social or individual, biological or psychic—remains a haunting element, for me, in this complex and richly ambivalent read.

Sylvia Nickerson, Creation (excerpt), 2019. Publisher: Drawn & Quarterly.

Sylvia Nickerson, Creation (excerpt), 2019. Publisher: Drawn & Quarterly.