My first encounter with Cliff Eyland’s bibliophilic work was in 1990, in the last of a series of exhibitions at Dalhousie Art Gallery surveying contemporary Canadian drawing. That exhibition contained unconventional meditations on drawing, and Eyland’s contribution consisted of a vast number of drawings, photographs and objets d’art on three-by-five-inch file cards held in a library card catalogue—a then standard-issue piece of steel library furniture with manifold drawers full of items filed year by year. Viewers were encouraged to sit and rifle through an exuberant cacophony of poetically categorized felt-tip doodles, surreal erotica and staid Victorian monochrome portraits—among much else.

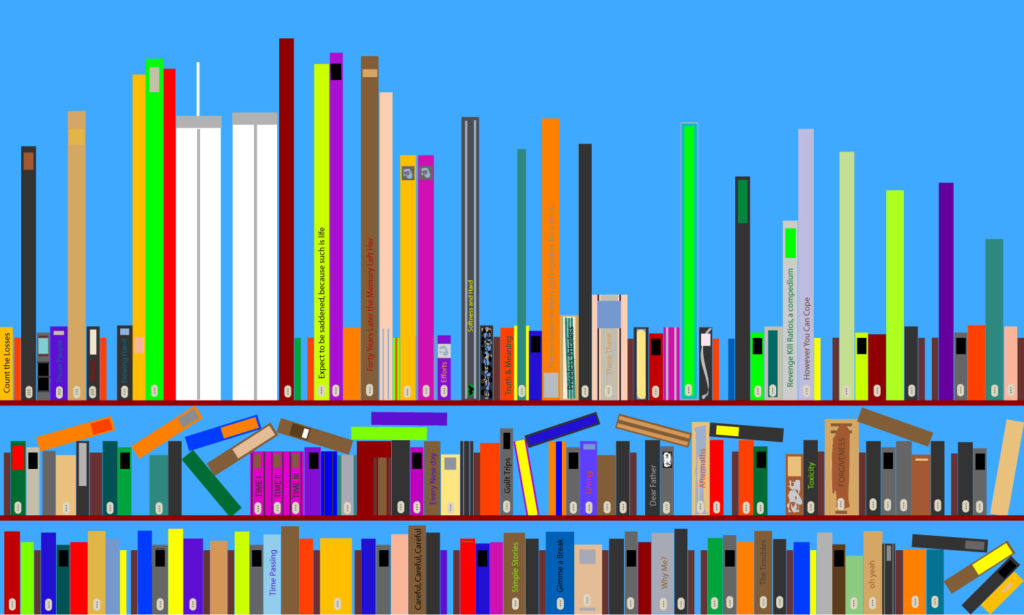

Eyland is keen on representing a lot in his exhibitions, from the bawdy to the learned, and libraries are an effective metaphor for this sort of comprehensive visiion. His current exhibition leans decidedly towards the learned, and represents an ideal imagined library of richly coloured book spines reproduced in miniature on ink-jet prints and then mounted on Eyland’s signature file card–scaled panels. Drawn with vector-graphics software, the spines of the books are mostly blank, but those that aren’t display the names of a range of authors, from William Blake to Sylvia Plath to Jeanne Randolph, as well as cryptic musings where the book titles would normally be. There are 110 panels in the exhibition.

The sources for these images are a pair of vector-graphics drawings that Eyland made while on a residency in New York City in the summer of 2001, just before the attacks on the World Trade Center. The drawings imagined New York in the form of three-tiered library shelving—the city as slender, rainbow-hued towers of publications, all neatly lined up, with the Manhattan skyline shaped from contrasting book spines. Looking back, there now seems to be a measure of innocence in Eyland’s gesture. One the other hand, Eyland was in the city in part to continue his ongoing project of concealing his file-card drawings in library books, this time in the New School University.

In keeping with this retrospective sensibility, the exhibition also includes diminutive geometric-abstract paintings. These succinct works present fragments of book spines executed in the classic 1960s hard-edge painting style, featuring layered acrylic paint—a fastidious process of gradual accrual, not unlike the effort that results in a carefully maintained personal library. While there is wordplay and cheeky colour in the show, this is not Eyland’s usual miasma of impish references, but a platonic proposition of library love.

Cliff Eyland, Bookshelf File Card LK 21—The Large Bookshelf, 2009. Ink-jet print on paper, mounted to MDF, 7.6 x 12.7 cm.

Cliff Eyland, Bookshelf File Card LK 21—The Large Bookshelf, 2009. Ink-jet print on paper, mounted to MDF, 7.6 x 12.7 cm.