Recent years—following decades of grassroots advocacy by disability rights activists—have seen increased public discussion about cultural institutions, the arts and accessibility. In 2019 alone, the second Cripping the Arts symposium took place in Toronto; the Museum of Surrey in BC announced it would debut sensory friendly hours and initiatives, following the advice of two people with autism; and there was public outcry at the Tate Modern in London and the Vessel in New York over inaccessible art installations.

This summer in Banff, the exhibition “Guidelines” made an effective case for how institutional accessibility can be a dynamic, responsive group effort—and a case for how the gallery and museum sectors need to do better in responding to, and supporting, differently abled artists and visitors. Carmen Papalia, a Vancouver artist and self-described “nonvisual learner,” worked with collaborators to achieve an environment where tactility and aurality were emphasized over visuality, both in the artwork and in its presentation.

Themes of interdependence, adaptability and changeability were manifest in audio works that echoed throughout the three-room exhibition. One of these sound elements consisted of Papalia’s walking cane tapping walls, sidewalks, steps and other materials. Another consisted of spoken-word storytelling where Papalia related experiences around developing what he calls, his “Open Access Framework”—a framework that emphasizes open-ended and flexible, rather than protocol- and policy-foreclosed, approaches to different needs.

Carmen Papalia and Heather Kai Smith, Open Access: Claiming Visibility, 2019. Installation view. Courtesy the artists. Commissioned by Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

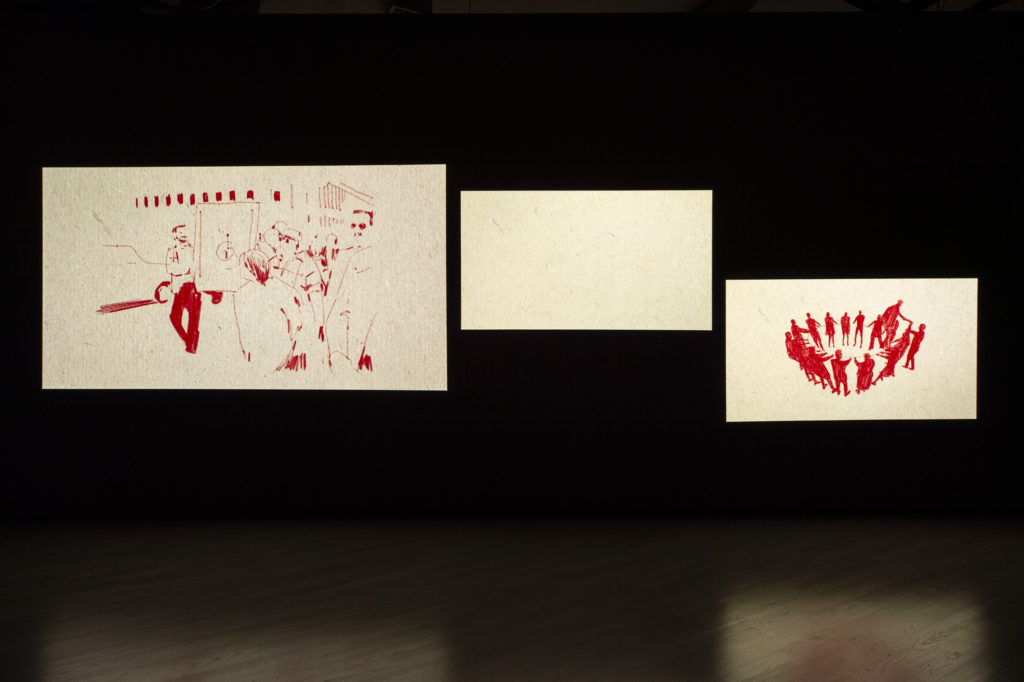

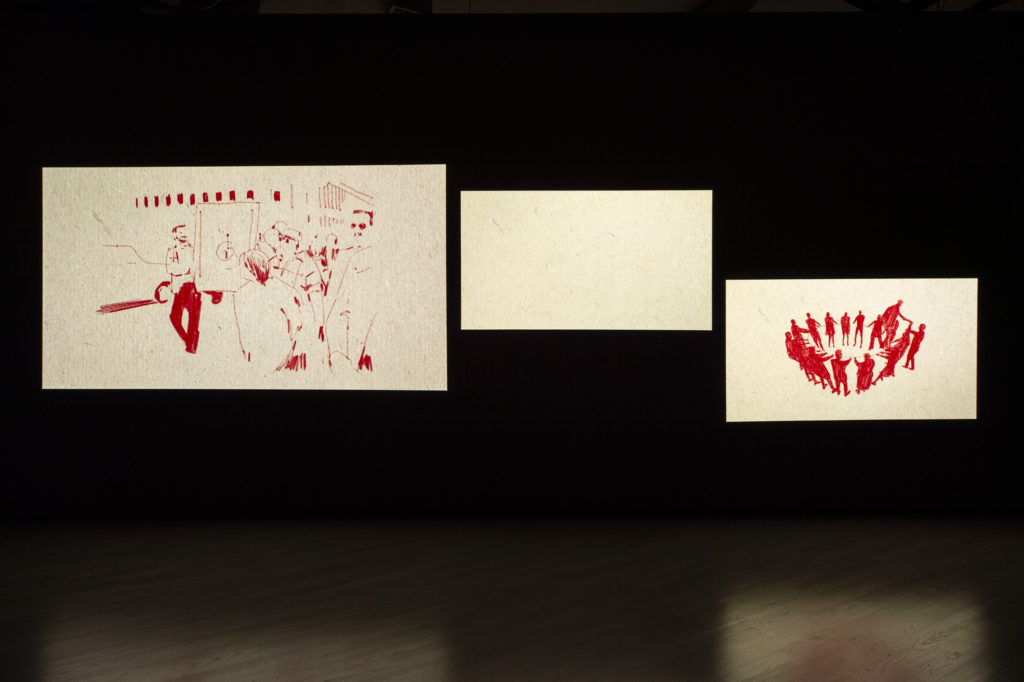

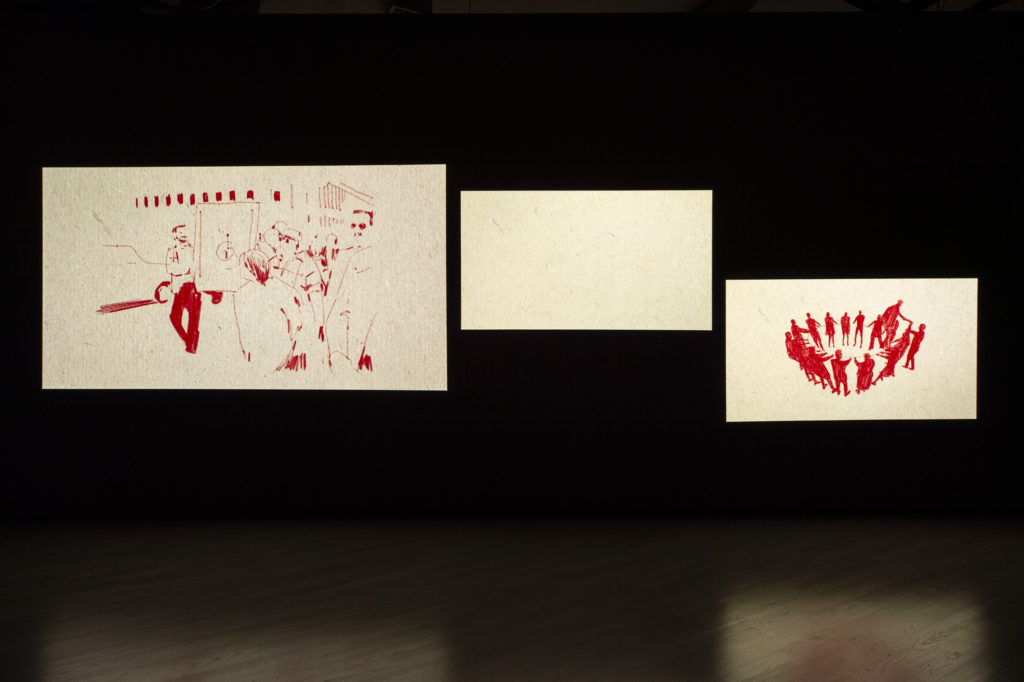

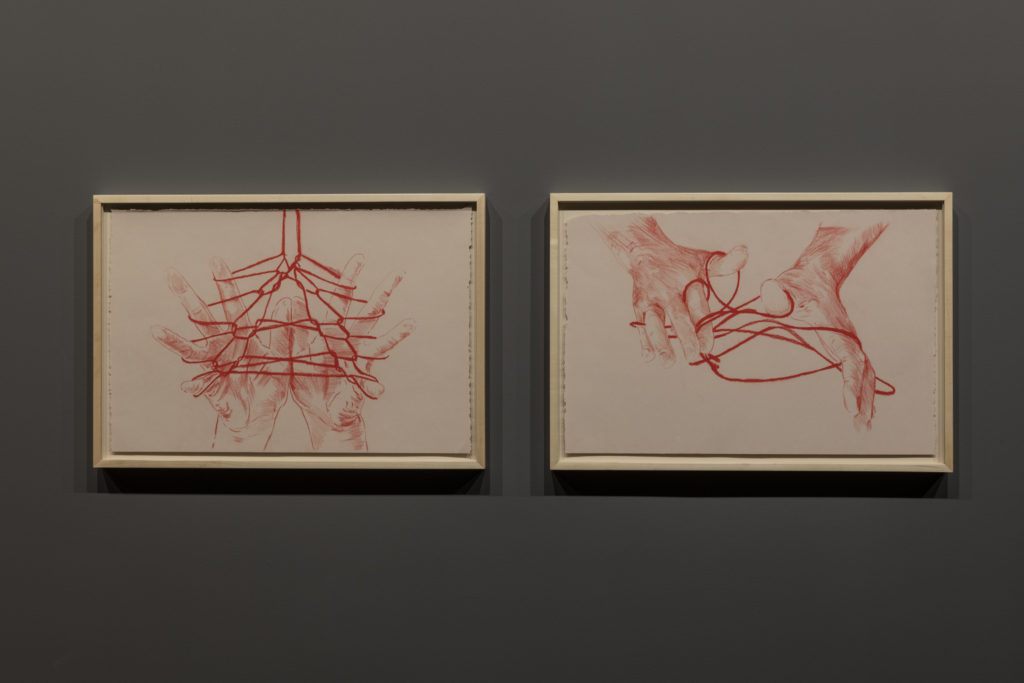

Installation view (left to right): Carmen Papalia, Red String, 2015–ongoing. Courtesy the artist. Carmen Papalia and Heather Kai Smith, Open Access: Claiming Visibility, 2019. Courtesy the artists. Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

Heather Kai Smith, Open Access: Claiming Visibility, 2019. Courtesy the artist. Commissioned by Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

“It was soon after I had a panic attack at the complex-pain clinic that I knew I had to plan for my next emergency hospital visit,” Papalia related in spoken-word audio. “I was filling out an intake form and the questions about the effectiveness of my care recalled a troubling experience: the time when the emergency room doctor refused treatment because he thought I was seeking drugs… It was [a] failure of trust in my most desperate moments, when I had no choice but to trust health professionals who were more bound to protocol than care.”

Papalia’s audio also noted that the gallery and museum sector has its own issues with protocols that privilege visuality above all else. “I didn’t realize the full impact of ocular-centrism until I told my friends who identified as blind about my work,” Papalia related. “Many of them had never been to a museum let alone considered pursuing art practice… The contemporary art landscape wasn’t organized so people like them could represent themselves or share their stories with a wider public. Instead the entire field privileged visuality—a tradition that not only repressed unseen bodies of knowledge, but excluded nonvisual culture with its own history from participating.”

Heather Kai Smith’s drawings and animations accompanied this audio in two of the three rooms in “Guidelines.” The structures she depicted—the string game Cat’s Cradle, parachute domes, trust exercises—are ones that rely on social cohesion and cooperation, on contingency and response, in order to exist.

Carmen Papalia, Red String (2015–ongoing). Installation view. Courtesy the artist. Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

Carmen Papalia, Red String (2015–ongoing). Installation view. Courtesy the artist. Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

Carmen Papalia, Red String (2015–ongoing). Installation view. Courtesy the artist. Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

The third room included an installation of 14 free-standing mirrored structures. These structures, developed in collaboration with Vancouver’s Goodweather Studio, also hold the possibility of being contingent and dynamic. (They may be arrayed, for instance, in different ways in the future as “Guidelines” and related projects tour to other venues.) As a visual learner myself, I found this space disorienting—mirrors and house-of-mirrors-like arrays are environments that complicate spatial navigation for those who are more visually oriented, but less so for people who navigate through touch and sound. To emphasize this point, a single red string was pulled taut across and around these mirrored structures. A wall text explained that this red string is similar to ones Papalia has used in the past, placing string in other art spaces and museums in order to aid his own navigation to frequently visited sites, like a café or studio.

While the red string placed by Papalia was one kind of guideline in this show, the animated video and drawings by Kai Smith, all done exclusively in red pencil, provided another. And the sound of Papalia’s cane tapping and the narratives he shared through spoken word were also kinds of guidelines. So, too, was the design of the exhibition itself, which left a lasting impression: grey-brown walls, low light, movable benches and an expanse in the final room of the show that, depending on one’s senses, some may think of as “blank.” But non-ocular-centric visitors might perceive this last area as filled with sound, offering the space and opportunity to reflect on where these models might take us next.

Heather Kai Smith, Open Access: Claiming Visibility, 2019. Installation view. Courtesy the artist. Commissioned by Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

Heather Kai Smith, Open Access: Claiming Visibility, 2019. Installation view. Courtesy the artist. Commissioned by Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

Heather Kai Smith, Open Access: Claiming Visibility, 2019. Installation view. Courtesy the artist. Commissioned by Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Photo: Jessica Wittman.

Heather Kai Smith, Open Access: Claiming Visibility, 2019. Installation view. Courtesy the artist. Commissioned by Walter Phillips Gallery, Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. Photo: Jessica Wittman.