It’s hard to sit still while watching Bugs and Beasts Before the Law, an experimental film by Bambitchell, the artistic collaboration of Sharlene Bamboat and Alexis Mitchell. The work consists of five chapters that each focuses on a different court case involving animals or objects. Unease comes, in part, from the combination of Richy Carey’s eerie score with Sukaina Kubba’s soothing voice. When paired with cinematography that alternates between scenic and psychedelic, and vibrant geometric title cards, the film puts the viewer into a state of hyperawareness. Watching with only two other people in the room, my response quickly shifted from a self-indulgent smirking over how ridiculous it was for animals to be tried over their supposed demonic possession, to realizing that, in some ways, we haven’t progressed that far from some of the film’s key issues.

The struggle with characterizing our relationship to the natural and inanimate can be traced back through time. Thinkers like Heidegger commented on the ways we Other the non-human by referring to them as “things.” This is paradoxical: on one hand, we want to shape the world around us to our liking and often expect the Other—whether they are a sow, cock, termite, elephant, or an object like a wheelbarrow—to behave like us. At the same time, we condemn them as something unnatural and below human.

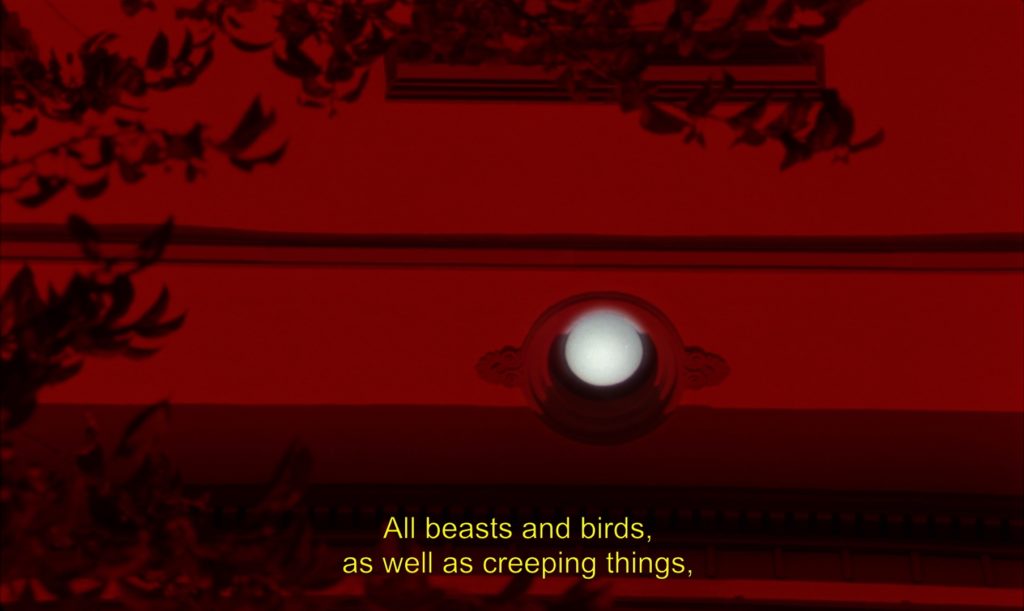

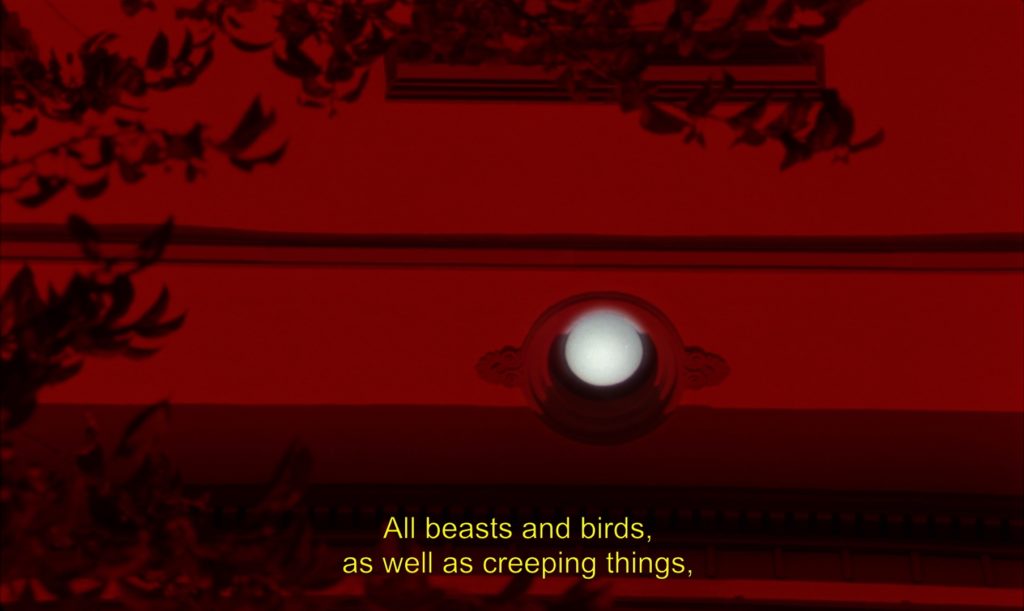

Bambitchell, Bugs and Beasts Before the Law (still), 2019. 4K video and 16mm film finishing on HD video, colour/sound, 33 min. Courtesy the artists.

Bambitchell, Bugs and Beasts Before the Law (installation view), 2019. 4K video and 16mm film finishing on HD video, colour/sound, 33 min. Courtesy Mercer Union. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

In exploring how “the history of colonial law-making forged political and sometimes profane relationships between humans and animals,” Bugs and Beasts establishes a link between the past and our current anxieties about climate change, the judicial system, and the insurance industry. In her accompanying exhibition essay, Sarah Keenan further highlights how the historical colonial project also saw slaves as objects, vulnerable to legal prosecution but deprived of personality. Bambitchell’s newest work acts as a necessary history lesson reminding us that the tendency to project human behaviour onto the natural world and to exploit what’s considered a resource has not changed, although the approach certainly has.

Walking out of the exhibition, today’s conversations about the rise of artificial intelligence and post-technological singularity (where technology’s growth irreversibly changes humanity) suddenly start to feel silly. It begins to sink in that we should not be having conversations about artificial sentience, often in a vacuum of science fiction, at a time when lex talionis—the medieval punishment of “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth” referenced by Bugs and Beasts—has transformed into a streamlined process for extracting resources. In one of the film’s chapters, Kubba narrates the horrific execution of an elephant as the viewer watches condos being built in an unnamed city. In that moment, there is a sense that we are not only using other living creatures as resources, but also clear-cutting them like we do trees to make way for a human-centric world. It is ironic that we have gone from thinking of other animals as humans and therefore executing them, to largely ignoring the fact that it is humans who are the greater threat, and our attempts to hide behind broken laws and logics can neither change that nor excuse us.

Bambitchell, Bugs and Beasts Before the Law (installation view), 2019. 4K video and 16mm film finishing on HD video, colour/sound, 33 min. Courtesy Mercer Union. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Bambitchell, Bugs and Beasts Before the Law (still), 2019. 4K video and 16mm film finishing on HD video, colour/sound, 33 min. Courtesy the artists.

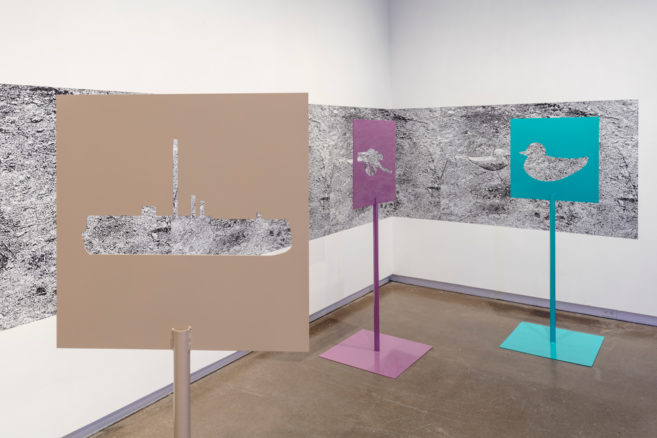

Bambitchell, Appendix (installation view), 2019. Print reproduction of select pages from the appendix of E.P Evans’s The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals, 1906. Courtesy Mercer Union. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Bambitchell, Bugs and Beasts Before the Law (still), 2019. 4K video and 16mm film finishing on HD video, colour/sound, 33 min. Courtesy the artists.

Bambitchell, Bugs and Beasts Before the Law (still), 2019. 4K video and 16mm film finishing on HD video, colour/sound, 33 min. Courtesy the artists.