One of theatre’s true pleasures is that it’s a space defined by a careful orchestration of optics. A desk with a telephone and computer gives the impression of an entire office environment, an actor walking with an opened umbrella suggests the current weather on stage—everyday objects create a realistic illusion through which disbelief is suspended and we slide into the magic of theatre. Photographer Angela Snieder made productive use of this visual immersion in her recent exhibition “Obscura.”

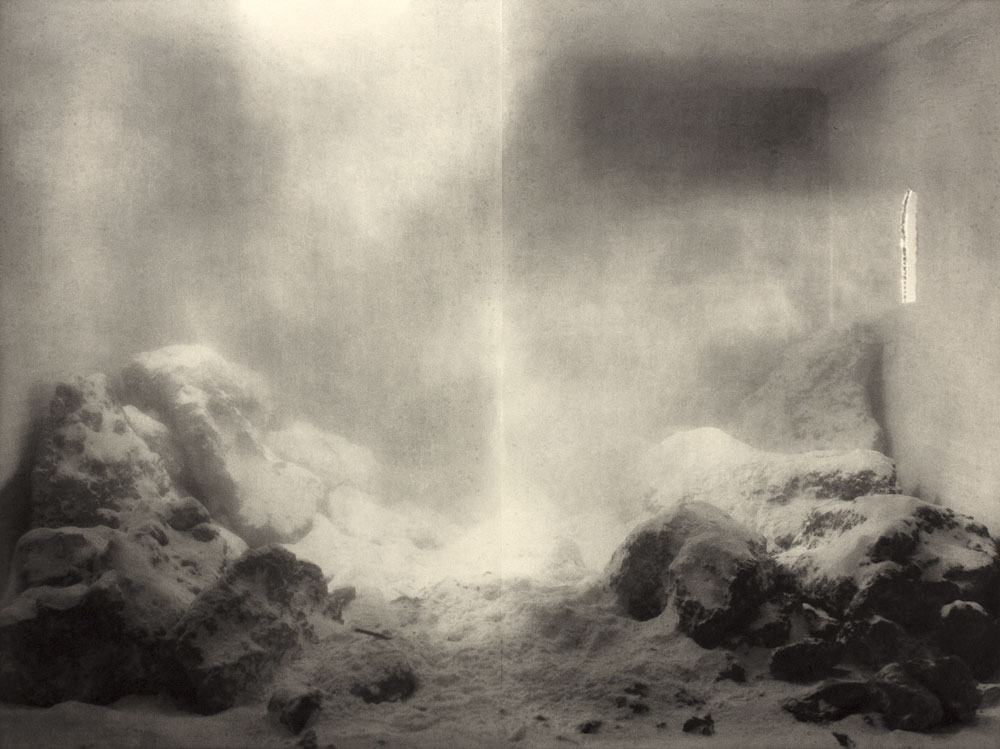

Works in the exhibition included photopolymer Chine-collé, wall-pasted digital prints and a camera projection, all outcomes of Snieder’s meticulous handling of perspective, lighting and props within the tight confines of a cardboard box. Her materials include everything from flour, twigs and clay, to found studio detritus such as bits of plastic, screws and crumpled paper. But these innocuous materials shapeshift within the monochromatic hues of her images. They recede into an obscurity and become unrecognizable. The final photograph, a seamlessness artificial construction, transcends mere documentation of the concoction in the cardboard box.

Each print in the show calls up a hazy desolate landscape, a murky cave or a field of grass. Snieder plays something of a Foley artist, not giving the viewer the full luxury of settling into the very fiction she’s conjured. In some of the works, Snieder reveals the edges of the makeshift cardboard box structures she adopts to create her illusionist landscapes. The proverbial fourth wall of the photograph is slyly broken in a self-aware gesture that points to the medium’s own artifice and situates the prints within multiple spatial modes: viewers find themselves in what feels like a disassociated dream state, but still able to sense the tangible world outside of it.

The projection takes this same penchant for deception and intensifies it with movement and wafts of sound. Projected in a darkened chamber—built by Snieder—is an assemblage of debris placed upside down to effect wind blowing through grass—or at least something that presents itself as such. Artists like Thomas Demand have created architectural sets out of stock paper and made them believable as existing livable spaces through photography. The fabricated environs of Snieder’s images hinge on a resemblance to landscape photographs. What we thought we knew suddenly looks strange and perhaps even surreal. It leaves us second-guessing and in doubt.

Angela Snieder, Storm 1, 2017. Digital print on Japanese paper (pasted to wall), 4 x 9 ft.; and Diorama 4, 2017. Photopolymer print on Japanese paper, Chine-collé on rag paper, 30 x 40 in. Courtesy Martha Street Studio. Photo: Ally Gonzalo.

Angela Snieder, Storm 2, 2017. Digital print on Japanese paper (pasted to wall), 9 x 6 ft. Courtesy the artist.

Angela Snieder, Field, 2019. Analog camera obscura projection (installation). MDF camera boxes, glass lenses, paper sculpture, found objects, light, wind, sound; camera boxes: 2 x 2 x 2 in., projection: 6 x 10 ft. Courtesy the artist.

Angela Snieder, Diorama 5, 2017. Photopolymer print on Japanese paper, chine-collé on rag paper, 30 x 40 in. Courtesy the artist.

Angela Snieder, Diorama 5, 2017. Photopolymer print on Japanese paper, chine-collé on rag paper, 30 x 40 in. Courtesy the artist.