Seeing, smelling—or even imagining—food causes the brain to react subconsciously, increasing the secretion of saliva. This literal “mouth-watering” facilitates the teeth’s chewing function, and the saliva’s amylase enzyme begins breaking down food before it enters the stomach and intestines. The nerves that control this process are part of an intricate reflex system.

Entangled biological and cultural systems, and the reflexes that serve to nourish us, are central to the “ALIMENTARY” project, curated by Su-Ying Lee. In the kitchen at Obrera Centro in Mexico City, three events led by artists Patrick Cruz, Tsēmā Igharas and Amy Wing-Hann Wong brought us together over (yes) mouthwatering food and tea to find sustenance in the transmission of cultural knowledge that simmers and steeps in the body.

Beginning the week with Sei Mei Tong, Amy Wing-Hann Wong led us through the preparation of her mother’s healing and fortifying broth. As pork neck simmered on the stove, Wong led us through a recipe that involved assemblages of dried fruits, seeds and roots laid out at each place on a communal table. She described the process of translating each ingredient into phonetic Cantonese, then into English and Spanish, and searching for them in Mexico. The transposition of the recipe from her mother’s traditional context to art worlds in Canada and Mexico invoked how recipes are living documents: as material and maternal practices, they act as scores for performances that transmit cultural memory and care as they change and grow across time and space.

Amy Wing-Hann Wong’s Sei Mei Tong as part of “ALIMENTARY,” Obrera Centro, Mexico City, 2019. Photo: Su-Ying Lee.

Amy Wing-Hann Wong’s Sei Mei Tong as part of “ALIMENTARY,” Obrera Centro, Mexico City, 2019. Photo: Su-Ying Lee.

The maternal imperative in Wong’s practice resonated with me, and drew me, my partner and our seven-week-old daughter to the project. Since becoming a mother, Wong has made questions of parenthood central to her work. Creating a space welcoming to little ones and valorizing the experience of postpartum—for instance, in discussing her grandmother’s version of geung cho, a postpartum meal—is political. Motherhood, in particular, is so often positioned as antithetical to artistic production. By sharing Sei Mei Tong and introducing the painstaking and communal process of creating geung cho, Wong manifested a social space that nourishes these interconnected facets of life↔work.

Animated by Wong’s intervention, I sat down with my mother-in-law and transcribed her recipe for what amounted to my own healing and rejuvenating postpartum meal: sopa de hongos, a Mexican mushroom soup with toasted corn, squash blossoms and epazote, seasoned with chipotle peppers. Armed with this recipe scrawled on a paper bread bag, my family and I arrived at the second event in the program, Patrick Cruz’s ongoing project Kitchen Codex. In Kitchen Codex, which Cruz has performed elsewhere, the artist prepares and serves a Filipino meal and invites the local community to eat—in exchange for a recipe in any language, to be compiled in a cookbook. Documenting the event in this way, Cruz creates a portrait of each community that convenes around the meal. In the context of Mexico City, this portrait looked like shared—and distinctly divergent—histories of colonization: the Philippines, Mexico and Canada as lands networked through tongues and guts.

Patrick Cruz’s Kitchen Codex as part of “ALIMENTARY,” Obrera Centro, Mexico City, 2019. Photo: Su-Ying Lee.

Patrick Cruz’s Kitchen Codex as part of “ALIMENTARY,” Obrera Centro, Mexico City, 2019. Photo: Su-Ying Lee.

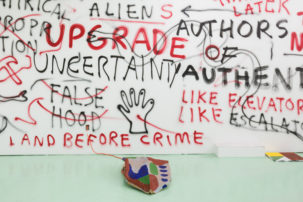

Whiteboard recipe at “ALIMENTARY,” Obrera Centro, Mexico City, 2019. Photo: Su-Ying Lee.

Tsēmā Igharas’s Glass Rocks and Caribou Weeds as part of “ALIMENTARY,” Obrera Centro, Mexico City, 2019. Photo: Su-Ying Lee.

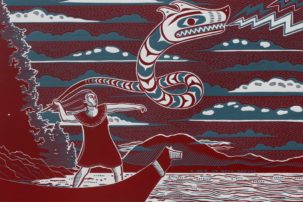

Tsēmā Igharas’s lecture-performance Glass Rocks and Caribou Weeds, the final event in the program, began with the artist crumbling caribou weeds into a teapot, covering them with boiling water and serving us the aromatic brew. Over tea, Igharas shared images of her various artist projects that explore the complexities of extraction and embodiment on Tahltan land. Igharas showed us photos of the caribou-weed harvest and the plants drying indoors after being foraged. She also recounted how her grandmother would compel members of her community not to share such images widely in order to keep the harvest secret and therefore safe from those who might be inclined to pillage. Igharas’s closing of the “ALIMENTARY” project thus reminded us that hospitality extended must always be respected—that sacred and ancestral knowledge, while it may be shared, must ultimately nourish sovereignty.

In my kitchen cupboard now, a month later, there is a small paper bag containing honey dates, Solomon’s seal root, dried lily bulb and apricot kernels: dried ingredients that form the base of Wong’s Sei Mei Tong, gifted by the artist to all in attendance. Like “ALIMENTARY,” this small gift contains within it the potential for joyous collisions of flavours and textures, waiting to be awakened and activated with boiling water, slow simmering and the addition of local meats and fruits. Each pot will taste different, each iteration shaping a new social space as we gather around to nourish ourselves, and each other.

Patrick Cruz’s Kitchen Codex as part of “ALIMENTARY,” Obrera Centro, Mexico City, 2019. Photo: Su-Ying Lee.

Patrick Cruz’s Kitchen Codex as part of “ALIMENTARY,” Obrera Centro, Mexico City, 2019. Photo: Su-Ying Lee.