Worlds In Motion

I felt like a kid at the Montreal Museum of Fine Art’s retrospective “Alexander Calder: Radical Inventor.” The solid colours, simple shapes and unpredictable movements brought out an uncomplicated sense of wonder in me. Which was not at all like when a friend and I sat outside in subzero temperature last month, staring up at an ominous, red full moon. It reminded me of the passages in Delany’s Dhalgren when the sun is about to crash into the earth: people felt the roiling heat penetrate their skin and there was really just nothing they could do about it. Staring up at the sky, neither of us knew what caused the moon to be red but rather than professions of wonderment, we were glib. We exchanged cynical one-liners and sinister jokes. It turns out that, during a lunar eclipse, a scattering of sunlight through the earth’s atmosphere causes the moon to appear a rusty red—hence the nickname, “Blood Moon.”

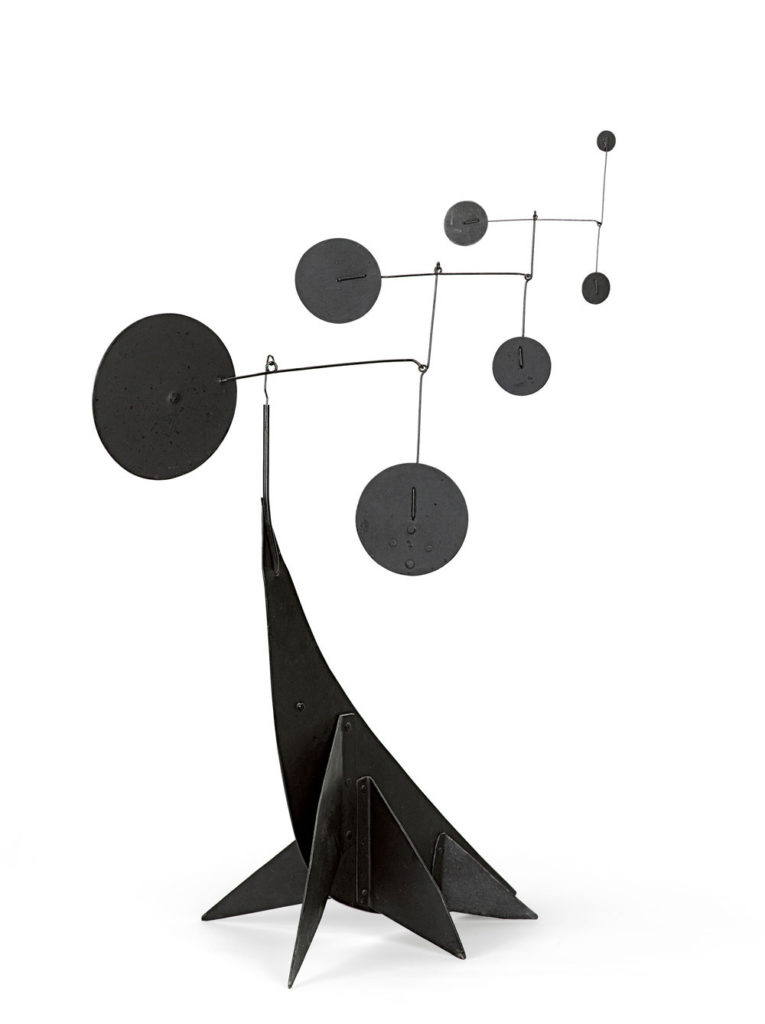

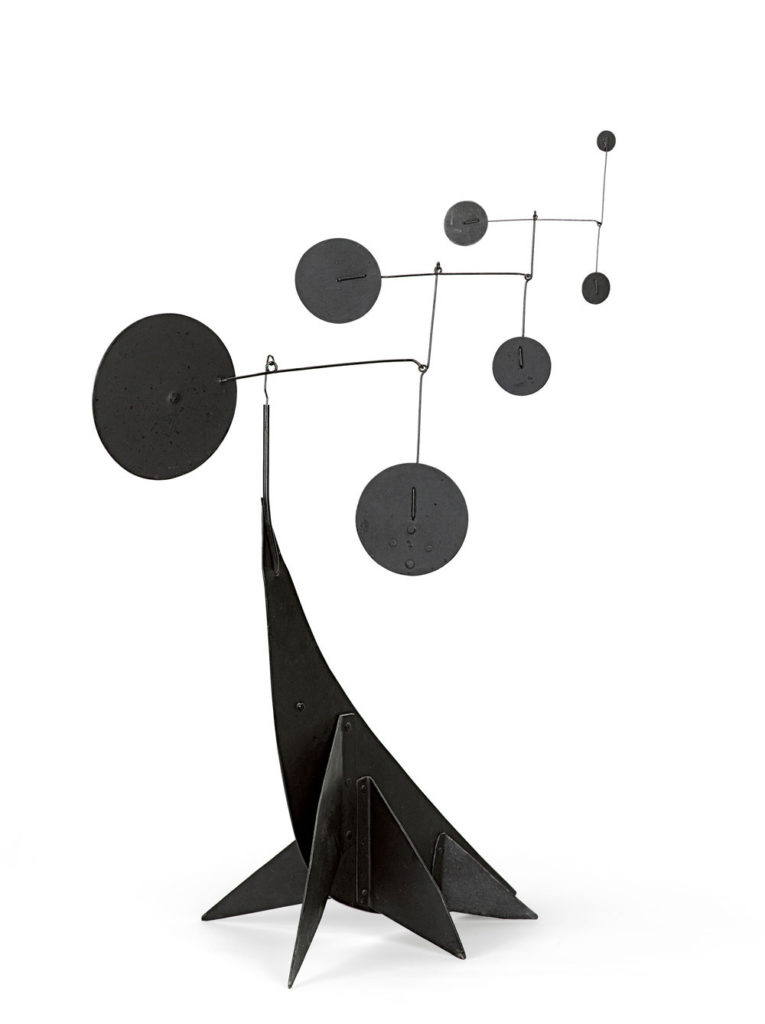

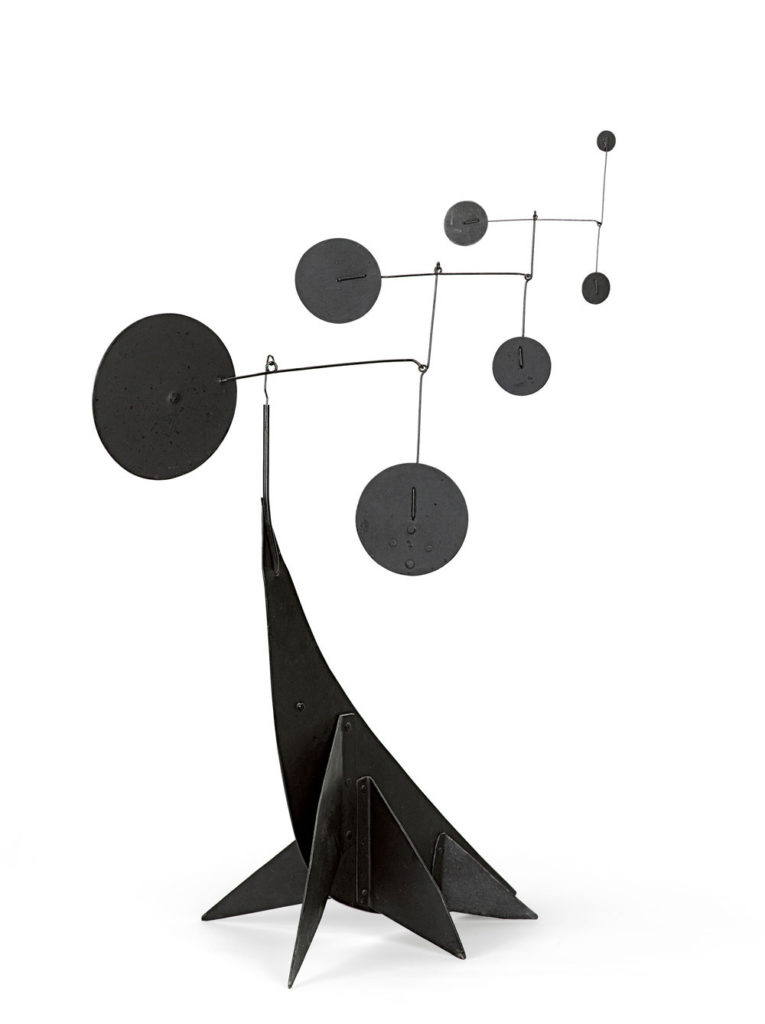

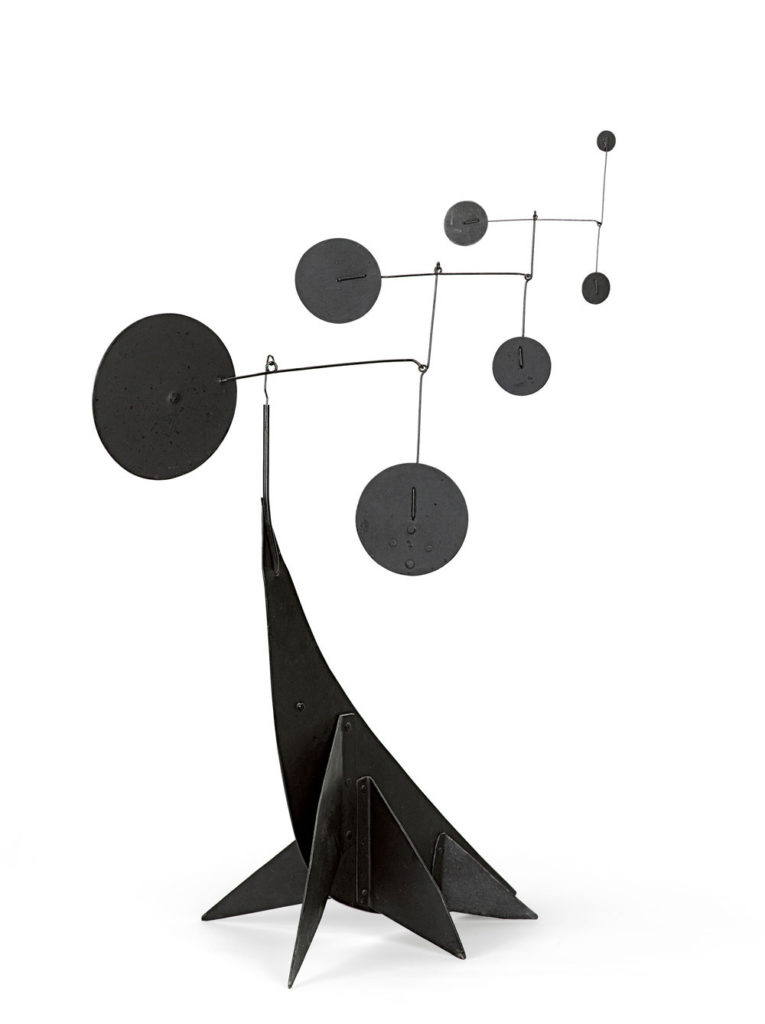

With an assemblage 150 pieces on loan from the Calder Foundation in New York and an assortment of museums and private collections from Canada, the US and Europe, the Calder retrospective is the first of its scale in Canada. The heart of the show is one big, brightly lit room. Along the white walls are custom-designed plinths with a variety of Calder’s individual “stabiles.” Hanging from the ceiling are the delicate, elaborate mobiles, which conjure something like dinosaur skeletons, suspended in space and time. At specific times throughout the day, a technician in a white lab coat comes in and uses a long, padded stick to gently tap the hanging pieces, waking them and bringing them to life. They shake and quiver, they shift and change, enabling endlessly different possibilities and configurations. In Bernard Carlson’s contribution to the catalogue (co-edited by renown Calder scholar Elizabeth Hutton Turner), he suggests that the discovery of abstraction was freeing for Calder. After studying engineering and earning a reputation with his representational wire sculptures, Calder’s mechanical and geometric abstractions are freeing, as seen in the generative coupling of his experimentation with aesthetics and scientific forms.

“This has no utility and no meaning. It is simply beautiful. It has great emotional effect if you understand it. Of course if it meant anything it would be easier to understand, but it wouldn’t not be worthwhile,” Calder is quoted to have said, regarding one of his motorized mobiles. For me, who hates CGI but loves science fiction, who never saw the Star Wars prequels let alone Avatar, there is something plain and tactile about Calder’s work that I find incredibly soothing. It’s the atmosphere it creates, the tone it sets, not what it does but what it is. It’s pre-internet, if that can be said to be a thing. It’s Beetlejuice over the new Grinch; the revelatory aspects of Sara Cwynar’s contemporaneity over the obfuscation in Jessica Eaton’s modernism. Calder never obscures the means—or materials—of the work’s own production. Like an eclipse, there is something scientific but simple at work in what he’s making but, unlike the eclipse, there is nothing foreboding here. Even when Calder’s metal sculptures, mobiles and stabiles dip into abstraction, they always feel transparent, dimensional, open.

—Yaniya Lee, Associate Editor

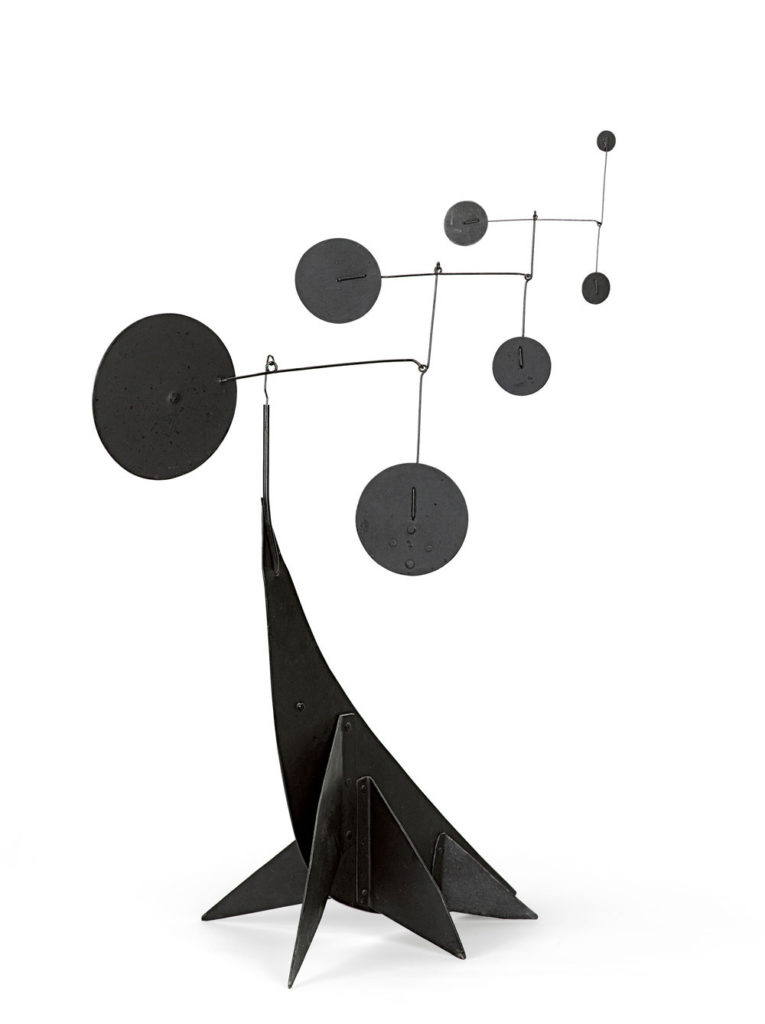

"Alexander Calder: Radical Inventor," (installation view), 2018. Exhibition presented at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts from September 21, 2018, to February 24, 2019. Photo: MMFA, Denis Farley. Copyright: © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal.

"Alexander Calder: Radical Inventor," (installation view), 2018. Exhibition presented at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts from September 21, 2018, to February 24, 2019. Photo: MMFA, Denis Farley. Copyright: © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal.

"Alexander Calder: Radical Inventor," (installation view), 2018. Exhibition presented at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts from September 21, 2018, to February 24, 2019. Photo: MMFA, Denis Farley. Copyright: © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal.

"Alexander Calder: Radical Inventor," (installation view), 2018. Exhibition presented at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts from September 21, 2018, to February 24, 2019. Photo: MMFA, Denis Farley. Copyright: © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal.

Engineered Abstractions

Abstraction is often considered a gesture of obfuscation: to abstract is to disconnect something from its physical, tangible, graspable, understandable presence. It is confusion—a re-ordering of physicality, a retreat from representation. But for Calder it was the opposite: the radical potential of abstraction was that it could reveal physical forces in the universe, like gravity or energy, that stubbornly resist visual representation.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Calder was working through spatial relationships between basic geometric forms—a sphere, a line or vector, a helix—alongside Einstein’s newly popular and newly verified theories of a non-Euclidean universe, which exists in four dimensions. Works like The Planet (1933) and Space Tunnel (1932) saw Calder experimenting (still in two-dimensional representation) with spheres and spirals, attempting to represent the bending of space or an active trajectory of movement. Similarly, Object with Red Ball (1931) appears as a sculptural diagram of the movement of planets and their circular orbits through the tensions of gravity. In Black Frame (1934), which appears to be a painting but is actually a kinetic sculpture, the illusory shadows created by the moving parts articulate something of the relationships between bodies and objects in space. But these experiments with representation, which anticipated the mobiles to come, were still very much contained by the grid and frame. When Calder later adds the element of time in the elegantly balanced mobiles, he reveals how objects relate to each other through universal, oppositional forces of gravity and weightlessness.

These works are, to me, the critical point of the show. They reveal an artist whose concerns were truly interdisciplinary, moving in step with advancements in physics and scientific observation and, like a true member of the avant garde, proposing new ways of thinking about the relationship between representation and form. Calder’s engineered abstractions of this era feel like the frames of a film reel—individually constructed scenes that demand to be read in sequence. When he untethers these experiments and allows the mobiles to float freely in space, it’s a bit like watching a series of unscripted films. The viewer becomes a part of his precisely ordered and self-contained worlds, worlds that suggest the power of a chaotic universe and forces which, though entirely physical, exist beyond our capacity to see. In an era before photographs of the earth from space were common, before there were ways to visually represent planetary bodies in the solar system, these were pretty radical ideas to articulate through abstract aesthetics.

—Jayne Wilkinson, Managing Editor

Alexander Calder, São Paulo, 1955. Oil on plywood. Calder Foundation, New York. Photo courtesy Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, New York. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal.

Alexander Calder, Red Gongs, 1950. Aluminum, brass, steel rod, wire and paint. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Fletcher Fund, 1955.Photo courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, New York. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal.

Alexander Calder, Aluminum Leaves, Red Post, 1941. Sheet metal, wire and paint. The Lipman Family Foundation. Photo courtesy Whitney Museum, New York. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal.

Alexander Calder, Jacaranda, 1949. Wire, sheet metal and paint. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, purchased 1977. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal.

Moving Parts

There was a special moment during the media preview last September. Among a handful of journalists circulating through one of the exhibition galleries, featuring an array of Calder’s hanging “mobiles” (a term famously coined for Calder by none other than Marcel Duchamp) and standing “stabiles” (named by Jean Arp), was the Montreal Museum of Fine Art’s Head of Conservation, Richard Gagnier. It’s rare enough for one of the museum’s behind-the-scenes specialists to make an appearance at a media preview, but Gagnier had a particular role to play. Dressed in a white technician’s coat and carrying a long, wooden pole with a padded tip (meticulously designed from polyester foam, cotton and high-tech nylon to avoid paint abrasion and friction), Gagnier stepped up to one of Calder’s sculptures and with an ever-so-gentle tap, set it in motion.

Gagnier continued to move around the room periodically setting works into action. To call this a revelation would be something of an overstatement (plus, journalists had been told what to expect in advance). But for someone whose previous exposure to Calder’s work has been largely limited to reproductions in magazines and exhibition catalogues, seeing these sculptures slowly turning, bobbing and swaying in the gallery seemed to suddenly unlock a latent but very much intended potential. Gagnier’s efforts notwithstanding, Calder’s work became much more than a masterful exercise in formal composition and sculptural engineering (though Calder was trained as an engineer). It is performative, expanding across the gallery in a play of intersecting shadows and movement. And in a way this idea of performance as an essential element of Calder’s thinking links back to another of his best-known projects, Cirque Calder, first created and performed in the late 1920s in Paris. It’s important to note here, too, that despite the fact that Calder himself would often activate his mobiles and stabiles in exhibitions, this fundamental kinetic aspect of his work has only recently been explored again in galleries and museums, first at the Whitney Museum’s 2017 retrospective and now in Montreal.

Along one wall of the gallery leading in to the mobiles and stabiles are a selection of earlier works that read as studies in Calder’s abiding fascination with movement and form: the delicately balanced, trapeze-like Starfish (1934), three-dimensional paintings White Panel and Blue Panel (both 1936) and the plinth-mounted, sculptural composition Black Frame (1934). In a show that ranged widely to create a master narrative of Calder’s life and career, this was a condensed curatorial space, a neat hinge that encapsulated a key moment in Calder’s experiments to break the picture plane and activate his work. As I mentioned to a colleague at the time, to me these works feel as fresh now as they must have felt eight decades ago. It was only later that I realized Black Frame is also a kinetic work, its components powered into syncopated motion by a hidden motor—another welcome reminder that what is familiar often carries the surprising potential to be seen anew.

—Bryne McLaughlin, Senior Editor

Alexander Calder, Performing Seal, 1950. Sheet metal, paint and steel wire. Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Leonard and Ruth Horwich Family Loan. Photo: Nathan Keay, courtesy MCA Chicago. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal.

Alexander Calder, Jean-Paul Sartre, 1947. Ink on paper. Calder Foundation, New York. Photo courtesy Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, New York. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal.

Alexander Calder, The Brass Family, 1929. Brass wire and painted wood. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, gift of the artist. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal. Photo courtesy Whitney Museum, New York.

"Alexander Calder: Radical Inventor," (installation view), 2018. Exhibition presented at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts from September 21, 2018, to February 24, 2019. Photo: MMFA, Denis Farley. Copyright: © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal.

Alexander Calder, Circus Scene, 1926. Gouache on canvas. University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, gift of Richard B. Bailey and Nanette C. Sexton in memory of Margaret Calder Hayes. Photo: Benjamin Blackwell. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal.

Alexander Calder, Molluscs, 1955. Oil on canvas. Calder Foundation, New York. Photo courtesy Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, New York. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal.

Alexander Calder, Molluscs, 1955. Oil on canvas. Calder Foundation, New York. Photo courtesy Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, New York. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOCAN, Montreal.