Based in Surrey, BC, since the 1970s, artist Jim Adams creates a visual narrative of epic perspective and movement, an archive of connective mythology and memory. His work is urgent in this moment when Black art and Black identities are being consumed by white collectors as if they are shiny new toys, in what is being hailed as a “Black Renaissance.” Previously, these collectors and the galleries they patronize were unaware or unwilling to acknowledge artists like Adams, who has been making important aesthetic contributions for more than 50 years. As one of only a few Black women operating an art project space in Los Angeles, I am grateful to experience Adams’s latest solo exhibition, “Eternal Witness” at Luis De Jesus Los Angeles, because of his layered, historically unapologetic and focused style and subject matter.

From his fascination with flying to his desire to see the world in its totality from space, Adams’s decades-long art pursuit seems as much about the scope of his journey as a Black man moving through time and mapping the coordinates of pleasure and meaning as it is about the paintings those experiences have produced. This is the visual literacy we need to engage now, so that instead of performing allyship through what’s trending, viewers come to understand how Black diasporic people, and specifically, one Black man, might interpret identity and mobility vis-à-vis painting.

Being Black is more than a notion. We carry history writ large on our skin. Labour, loss and love conflate as we navigate systems of exoticization, exploitation and erasure. Yes, it is systemic, foundational to racializing institutions and the public spheres where we are meant to quietly please, perform and then disappear. We are not a monolith, yet, as Adams told me, he calls the African Diaspora in the West “our own clan,” since we are of a diversity unrepresented anywhere else in the world. Our communal intimacies reflect shared experiences and give us the latitude to talk across genre and place. These realities existed as something illicit in the commodification of our cultural capital, until the world woke up in 2020.

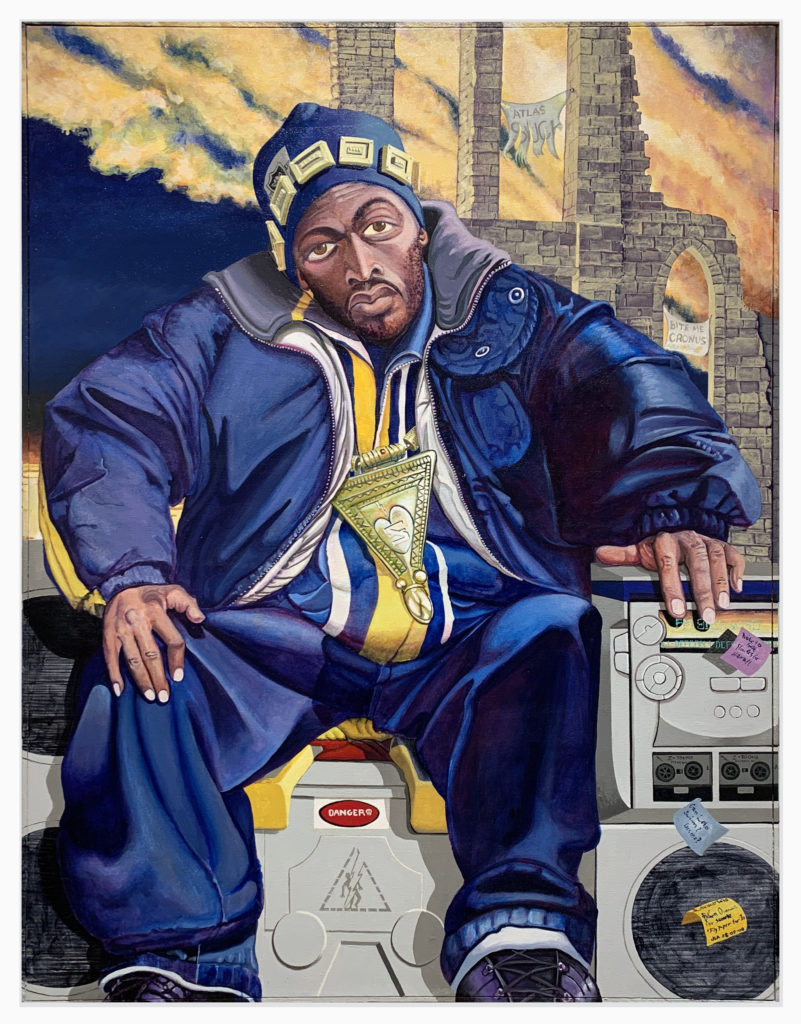

Jim Adams, Lil Zoose, 2008. Acrylic on canvas and hand-painted artist frame, 121.9 x 91.4 cm. Courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Jim Adams, Lil Zoose, 2008. Acrylic on canvas and hand-painted artist frame, 121.9 x 91.4 cm. Courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Adams focuses his visual language through the intersectional lens of the complexities, pleasures and perils of being a Black man in this world, now and otherwise. For example, Lost Trophy (Apollo) (2012) depicts the Greek god of truth, creativity and healing as a young Black athlete. Adams uses his own experiences as well as African and mythological allegories and parables—all made visual through rich colours, sacred geometries, real and metaphorical portals, land/space-scapes and portraits. Together, they suggest that the lineage of Black people and our creative vitality is as nimble as ever.

Adams holds up a mirror to the viewer and to himself as he culturally and physically locates us in the universe that has, by design, kept him in a state of what W.E.B. Du Bois described as double consciousness, or what is referred to today as code switching—the need to maintain multiple cultural knowledges to employ in different contexts. Adams adeptly disrupts the sense of fixed positionality by painting in multiple scales—micro, meta, liminal and universal—from the sculptural, three-dimensional Minor Sun paintings (2000–1), to his small sketches and autobiographical painting of a Black man in a Canadian spacesuit (Nubian Express / Exploration (The Artist Explores his Life), 2019). His transitional imagery signifies visual and historical reference points that in aggregate construct the arc of his/our narrative as energetically mobile people.

Jim Adams, Nubian Express / Exploration (The Artist Explores his Life), 2019. Acrylic on canvas and hand-painted artist frame, 76.2 x 101.6 cm. Courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

Jim Adams, Nubian Express / Exploration (The Artist Explores his Life), 2019. Acrylic on canvas and hand-painted artist frame, 76.2 x 101.6 cm. Courtesy the artist and Luis De Jesus Los Angeles.

This aesthetic project spans time—metaphorically and in the act of making. Adams sees the ancient pyramid as an essential feature that informs his language, one that he plugs in and scales up and down, back and forth, shifting perspective and the sense of permanence we often attach to cosmologies. He explores his relationship to categorization through the Minor Sun paintings, dislocating our common marginalization of other suns as mere stars by expanding the boundaries of the canvas. Drawing on ancient Egyptian and Greek gods, Adams aligns his imagery with original influences of pantheons where the gods faced adversities. And there is no better visual of overcoming struggle than the contemporary Black man.

In my view, Adams’s oeuvre is a documentation of his journey as it unfolds. Every painting is a step into memory, cellular and otherwise, the preservation of progress, the cartography of personal expression and experience. No one should get to consume Adams’s work without having literacy in the paths he has taken to make it.

Jim Adams’s “Eternal Witness” is on view at Luis De Jesus Los Angeles until February 27, 2021. An online viewing room accompanies the exhibition.