Preview week at the Venice Biennale is a moment when big money and VIP access is prized, and exclusivity is the ticket.

Artnews’ Yacht Watch has already begun. The Art Newspaper has polled a luxury hotel concierge on where to eat. And Artnet News just posted “A Buyer’s Guide to the Venice Biennale: What Collectors Need to Know About the (Technically) Noncommercial Event.”

But the members of Isuma artist collective—the first Inuit makers to be featured at the Canada Pavilion in Venice—have decided to do things differently.

First, all the films and livestreams Isuma is screening in the Canada Pavilion—including the new Inuktitut-language feature One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk—are also available online at isuma.tv or Isuma’s iTunes. So is The Isuma Book. That way, viewers in Inuit Nunangat and beyond can access the art too, in a parallel way.

Second, rather than focusing solely on their own productions about Inuit life, Isuma, during this International Year of Indigenous Languages, is shining a light on more than 7,800 Indigenous community videos in 70 languages. On Isuma.tv, there are two videos in Maori, 13 in Sami, two in Yindjibarndi, and one in Tzeltal, just to name a few examples.

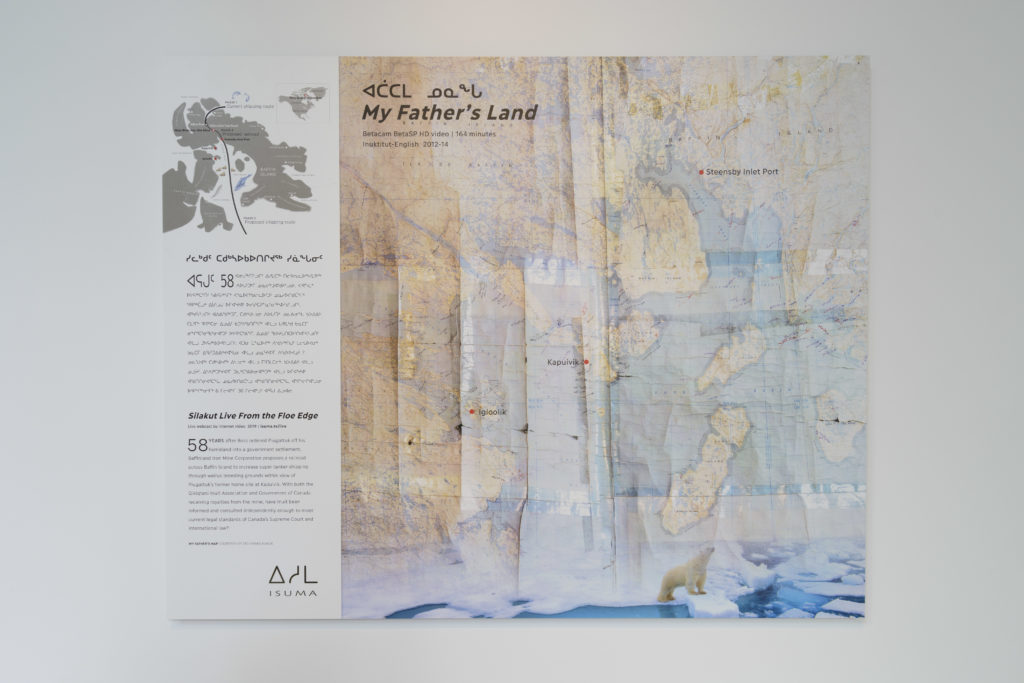

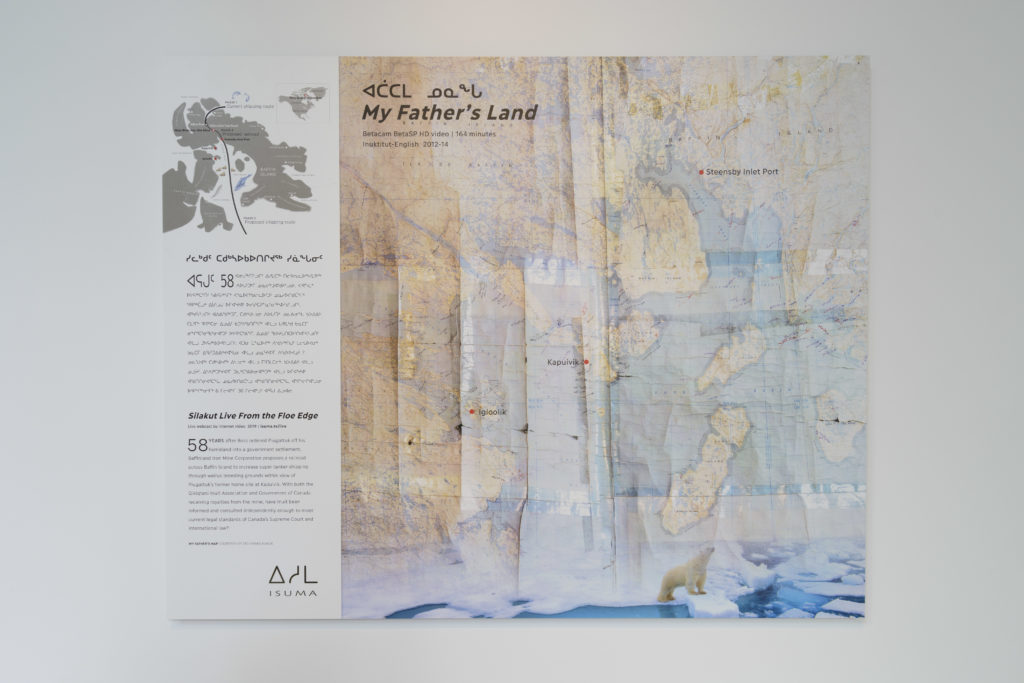

Third, though the Venice Biennale is often treated as a centre from which culture is broadcast to the world, Isuma is treating Inuit Nunangat as that centre. For the project Silakut Live from the Floe Edge, Isuma co-founder Zacharias Kunuk will be directing live broadcasts from northern Baffin Island that will be viewable in the Canada Pavilion and at isuma.tv, as well as at Canadian venues like the Art Gallery of Alberta in Edmonton and the Cinéma Moderne in Montreal.

“Silakut means ‘through the air,’” Zacharias Kunuk tells Canadian Art from Igloolik. “We plan to film live at our floe edge, from the ice and the sea, where hunters hunt seals, and broadcast halfway around the world to Venice.” (He adds: “We already did a test with Venice last week…And it worked, even though we were in a blizzard.”)

Zacharias Kunuk during the production of One Day in the Life of Noa Piugattuk. Copyright Isuma Distribution International, 2019. Photo: Levi Uttak.

Zacharias Kunuk during the production of One Day in the Life of Noa Piugattuk. Copyright Isuma Distribution International, 2019. Photo: Levi Uttak.

One Day in the Life of Noa Piugattuk on display as part of Isuma, 2019, at the Canada Pavilion for the 58th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, May 2019. Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Canada and Isuma Distribution International. Photo: Francesco Barasciutti.

One Day in the Life of Noa Piugattuk on display as part of Isuma, 2019, at the Canada Pavilion for the 58th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, May 2019. Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Canada and Isuma Distribution International. Photo: Francesco Barasciutti.

One of the main things Kunuk wants to address in Silakut is the impact of iron-ore mining in the Baffin Island region.

“We are one of several communities impacted by mining, and nobody really talks about it, especially here in Igloolik,” Kunuk says. “We thought, why don’t we talk about it, so that people are informed?”

The Mary River Mine near Igloolik, operated by Baffinland, only came into production in 2015, and it is already shipping more than 5 million tonnes of iron ore a year despite environmental concerns. Over 70 ships hauled ore out of Milne Inlet in 2018. With production and export planned to double and triple in coming years, the need for conversation is becoming more urgent.

“In 2025, just six years from now, they plan to have super freighters coming through to load up iron ore, like two or three ships a day,” says Kunuk. “Imagine these ships waiting around our area—our hunting areas—and we are not talking about it.”

Shipping routes for the ore in Nunavut are being widened by climate change. And climate change, especially the way it affects Inuit, is another subject Kunuk hopes to expose and address in Silakut.

“The land is melting, and we want to show that this summer,” says Kunuk. “We want to be in the traditional land where Inuit used to harvest—and it’s now covered with moss. We want to talk with elders about what they think will happen in the future. I want to talk to young people: how do you approach climate change?”

Apayata Kotierk as Noah Piugattuk and Kim Bodnia as Boss in a scene from One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk (2019). Copyright Isuma Distribution International. Photo: Levi Uttak.

Apayata Kotierk as Noah Piugattuk and Kim Bodnia as Boss in a scene from One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk (2019). Copyright Isuma Distribution International. Photo: Levi Uttak.

The new feature Kunuk has directed, One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk, raises many important questions, too.

Shot on location on Baffin Island, based on actual events in the 1950s and 1960s, and filmed mostly in the Inuktitut language, One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk captures a key moment of colonization in action—a centuries-old web of oppression, and resistance, in one interaction.

The new film, written by Isuma co-founder Norman Cohn, centres on a conversation between the titular Inuit hunter and a white man called the Boss. This government agent tells Noah Piugattuk that he must move to a settlement and start his children in school—that it’s the law, and that he will not receive a family allowance from the government unless he does so.

“I wanted to look at the moment that they [Inuit] were told to move,” says Kunuk. “They were saying, ‘We don’t want to go anywhere. We don’t want to move.’ But they were told they had to. So that’s what we’re looking at.”

In the film, Piugattuk tells the white man who’s pushing for forced migration that “it’s not going to happen.” But the sad fact is that for many Inuit, it did end up happening. And that includes Zacharias Kunuk himself.

“I was just starting to learn from my father how to drive a dog team,” Kunuk recalls. “And I thought, pretty soon, I’m going to have my own dog team. But then, at nine years old, I was sent to school.”

Some of Isuma’s other films have had expansive timelines, but the tight focus on one telling day, or one telling moment, around forced migration seemed right for 2019. The Boss’ presence and authority is tied up with the church as well, a matter of some discussion among Piugattuk and his friends in the film.

“We have made films about Inuit a thousand years before contact with Christianity, like Atanarjuat The Fast Runner,” says Kunuk. “And we have made films about the introduction of Christianity to Inuit, like The Journals of Knud Rasmussen. We thought it was a good time to do this.”

Isuma, 2019. Installation view at the Canada Pavilion for the 58th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, May 2019. Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Canada and Isuma Distribution International. Photo: Francesco Barasciutti.

Isuma, 2019. Installation view at the Canada Pavilion for the 58th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, May 2019. Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Canada and Isuma Distribution International. Photo: Francesco Barasciutti.

Isuma, 2019. Installation view at the Canada Pavilion for the 58th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, May 2019. Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Canada and Isuma Distribution International. Photo: Francesco Barasciutti.

Isuma, 2019. Installation view at the Canada Pavilion for the 58th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, May 2019. Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Canada and Isuma Distribution International. Photo: Francesco Barasciutti.

The new feature film also includes an archival video clip of the real-life Noah Piugattuk, who lived from 1900 to 1996 and witnessed many changes and pressures put on his people. Kunuk hopes the film serves an homage to Piugattuk, as well as an contemporary call to action and reflection.

“He was unique man who lived all his life on the land,” says Kunuk of Noah Piugattuk. “He ran on the bouncing ice. He was the walrus hunter. He saw the hunting of whales for fat so that they could light up the streets of London, which killed most of the whales, and then us Inuit were forbidden to hunt them. Then he ordered a bowhead to be harvested before he died, and there was a big controversy with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans—but he got his wish. He was a very important man for us.”

Noah Piugattuk’s strong stand for Inuit ways of life may also be echoed in the final Silakut Live from the Floe Edge broadcasts in late September.

That’s when Kunuk hopes to bring Isuma’s video cameras to Nunavut Impact Review Board hearings about a Phase 2 expansion of the Baffinland iron ore mine. Already, marine biologists have raised concerns about the existing mine’s impact on narwhal—and, in turn, upon narwhal predators. As both those animal populations shift, so does Inuit life and food supply.

Kunuk hopes to speak to interveners at the hearing, and webcast the proceedings that have so much at stake for Inuit.

As he puts it, “There are a lot of questions that I want to ask.”

Isuma, 2019. Installation view at the Canada Pavilion for the 58th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, May 2019. Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Canada and Isuma Distribution International. Photo: Francesco Barasciutti.

Isuma, 2019. Installation view at the Canada Pavilion for the 58th International Art Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, May 2019. Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Canada and Isuma Distribution International. Photo: Francesco Barasciutti.

Previews at the Canada Pavilion in Venice take place May 8, 9 and 10, with the Venice Biennale opening to the public May 11 to November 24. The parallel online version of the Isuma’s Venice exhibition is available now at isuma.tv, with Silakut broadcasts also streaming there daily May 8 to 11 from 9 a.m. to 12 p.m. EST and 4 p.m. to 8 p.m. EST. More information about future broadcasts will soon be available.

Mallik (Jacky Qrunnut) and Japati (Gouchrard Uttak) see a dogteam coming in a scene from One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk (2019) Copyright Isuma Distribution International. Photo: Levi Uttak.

Mallik (Jacky Qrunnut) and Japati (Gouchrard Uttak) see a dogteam coming in a scene from One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk (2019) Copyright Isuma Distribution International. Photo: Levi Uttak.