Asinnajaq, also known as Isabella Rose Weetaluktuk, is a visual artist, filmmaker and writer. She also curated a program celebrating 30 years of Inuit film at the most recent edition of ImagineNATIVE.

Asinnajaq, also known as Isabella Rose Weetaluktuk, is a visual artist, filmmaker and writer. She also curated a program celebrating 30 years of Inuit film at the most recent edition of ImagineNATIVE.

A qulliq is lit slowly. This lamp provides light and warmth, can be used for cooking and has been integral to survival for Inuit. Its bowl is filled with fat while arctic cotton is placed alongside as the wick. Though it is lit slowly, it burns for a long time.

The image of a qulliq was also at the centre the film that flickered the Channel 51 Igloolik screening to life at the latest edition of ImagineNATIVE. This celebration of 30 years of Inuit film was curated by Inuk filmmaker Asinnajaq (Isabella Rose Weetaluktuk), who is from Inukjuaq and Montreal and who has also curated other Channel 51 Igloolik programs for 2018, like the ones opened this week at Humber Galleries.

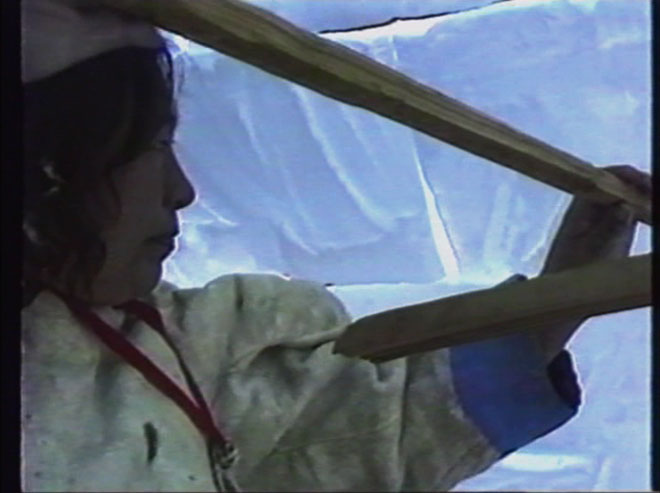

In that opening film at ImagineNATIVE, Qulliq (1993), the only sound is of two women who sing and talk as one of them prepares the lamp. Not only did this intimate, beautiful film begin the Channel 51 screening; it also showed the warmth of relationships and care in simple acts of singing and lighting a fire.

Qulliq (1993), a short Arnait film by Susan Avingaq, Madeline Ivalu and Marie-Hélène Cousineau, shows the warmth of relationships and care in Inuit culture.

Qulliq (1993), a short Arnait film by Susan Avingaq, Madeline Ivalu and Marie-Hélène Cousineau, shows the warmth of relationships and care in Inuit culture.

Qulliq, created by Susan Avingaq, Madeline Ivalu and Marie-Hélène Cousineau, was also the earliest film in the Channel 51 screening, a gesture which pointed to the long legacy of filmmaking by Inuit collectives Isuma, Arnait and Artcirq. The other films in the program were Aqtuqsi (1996), Unikausiq (1996), Issautuq (2007) and Bowhead Whale Hunting With My Ancestors (2017).

At the Inuit Art Foundation, where I work as programs coordinator, we were excited to sponsor the Channel 51 Igloolik screening and reception. Supporting Inuit artists is what we do, and this series of events was an exciting moment for Inuit art, an art that reaches beyond drawings, prints and sculptures to performances and moving images—with this moving-image art to finally be highlighted at the 2019 Venice Biennale, too.

As I watched the five films chosen for Channel 51 Igloolik—which were presented chronologically, with each one encompassing Inuit ways of life—I felt my friend Asinnajaq’s love intertwined throughout her careful, intentional curation.

Every film in the screening was chosen for us viewers in this moment, yes, but also for Inuit past, present and future. Unfolding through the program was a story of 30 years of film creation. Over this time, Isuma, Arnait and Artcirq collectives have worked to make Inuit ways of life visible and accessible for all.

One of the two women in Qulliq (1993).

One of the two women in Qulliq (1993).

Isuma was the first Inuit independent film production company in Canada whose focus was, and still is, to highlight and capture Inuit culture. Arnait has worked to create a specific platform for the voices of Inuit women through film. And Artcirq was developed in response to the enormity of suicide by Inuit youth; it is an Inuit performing arts and new media collective that works primarily with younger people.

In speaking about how she began thinking through how the films would sit together, Asinnajaq reflected: “When I started working on the retrospective, I watched almost everything that they [Isuma, Arnait and Artcirq] made. It’s all very beautiful and interesting and relevant, especially because what I want to do every day is try to learn about Inuit—both contemporary and historical.”

As she watched these films, Asinnajaq took notes on what the greater body of cinema showed. “There are some recurring themes: there is a lot of hunting; there are a lot of things about animals and environment and cultural heritage.”

But there was room for “only a few short films” in the Studio 51 Igloolik program. Qulliq stood out because “it’s beautiful, it has strong women and you learn through something beautiful.” It shows us care and love through simple moments of creating warmth.

Carol Kunnuk and Zacharias Kunuk’s Bowhead Whale Hunting With My Ancestors (2017) sheds light on the rich history and culture of Inuit whale hunting. Photo: Copyright Jan Kraus.

Carol Kunnuk and Zacharias Kunuk’s Bowhead Whale Hunting With My Ancestors (2017) sheds light on the rich history and culture of Inuit whale hunting. Photo: Copyright Jan Kraus.

Aqtuqsi (1996), or “my nightmare,” an animation directed by Mary Kunuk, shows a nightmare that is more sinister than a bad dream. Kunuk’s nightmare is a force that paralyzes you when you sleep. Unikausiq (1996), meaning “stories,” is also directed by Mary Kunuk, and it allows viewers to see and hear stories and songs from her memory.

Bruce Haulli’s Issautuq (2007), or “waterproof,” recounts the story a young Inuk man who becomes violent to himself and others after losing someone he loves. As a result, he is exiled from his town to a small camp where only three other people are living together in one small house. This man’s struggles and loss are confronted as he learns about another kind of love: love of family and of Inuit ways of being. In understanding the struggle and survival of his own family, he sees where he could go.

The final film in the Channel 51 Igloolik program was the world premiere of Carol Kunnuk and Zacharias Kunuk’s Bowhead Whale Hunting With My Ancestors (2017). In 2016, Igloolik was given the opportunity to hunt a bowhead, and these filmmakers highlighted the entire process, from the dry signing of legal papers to the joyous success of having harvested the whale. There were moments when the screening audience, too, laughed, became frustrated, and celebrated. I loved that the program ended with this film; it was funny at times, serious at times and it pointed to how far so many have to go to today do something that ancestors have always done.

A scene from Carol Kunnuk and Zacharias Kunuk’s Bowhead Whale Hunting With My Ancestors (2017), an Isuma production.

A scene from Carol Kunnuk and Zacharias Kunuk’s Bowhead Whale Hunting With My Ancestors (2017), an Isuma production.

In discussing why she included Bowhead Whale Hunting With My Ancestors in the program, Asinnajaq explained that it was an important addition, telling a story of bringing people together, but also “because [the screening] was considered a retrospective, but Isuma, Arnait and Art Cirq are still active, it made more sense as a program to end with the most contemporary thing.”

The reception for this screening was held at Trinity Square Video, where Asinnajaq had curated a related exhibition titled “Channel 51 Igloolik – The Filmmaking Process.” This exhibition brought together objects and props used in Isuma, Arnait and Artcirq productions through the decades, and as such, it was a room filled with items and images that had told integral parts of captivating filmic stories over 30 years.

In Igloolik, “they have a big crate or shipping container that has all of the costumes [and props] in it,” Asinnajaq explained. “I made a list of all the things that I would like … two jackets, tools or beading, et cetera. I asked while thinking that I might not get it all, or thinking, ‘What will happen, will happen.’”

Once all the objects came together in Toronto, they brought decades of creativity and innovation back into one small space.

The prop feet used in the film Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001), for instance, sat alongside sealskin outfits and accessories in the exhibition. When we see these objects in conversation with a long history of film, it is interesting to think about the role that these objects and their creation have contributed to the telling of stories. I know that when I was watching Atanarjuat running across the ice onscreen years ago, I thought a lot about his feet. So, upon noticing the feet casts at Trinity Square Video, I knew what they were immediately. These casts were used in that same iconic scene.

The front wall of the exhibition had a row of photographs lined up across it. “The photographs on the wall,” Asinnajaq said, “began with Lucy Tulugarjuk with her hands up”—an image chosen for its beauty and also because “she directed the last film for Arnait, which is in production right now.”

I often think about the process in which brilliant filmic moments begin; sometimes a process is simple, and we roll with what comes; sometimes it is careful and deliberate. In the Studio 51 Igloolik screening and exhibition, Asinnajaq pointed to Inuit filmmaking as a precise and contemporary practice that is moving forward.

And Asinnajaq, too, is part of that moving forward of Inuit film. At ImagineNATIVE, her film Three Thousand (2017) won the Kent Monkman Award for Best Experimental Work. In this film, Asinnajaq laces together archival footage, sound and animation. The film is an envisioning of the year 3000, and in that year, Inuit are building sustainable and thriving communities. (Asinnajaq is also part of the curatorial team working towards the opening of the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s Inuit Art Centre in coming years.)

As Asinnajaq suggests in her essay for the Channel 51 exhibition, lives, once captured on film, can still carry on as they had before that moment. Inuit are capturing their ways of life in interesting, beautiful and challenging ways, and as Asinnajaq’s film Three Thousand shows, into a very distant future.

A new Channel 51 Igloolik project curated by Asinnajaq runs from January 22 to April 14 at Humber Galleries L Space and March 5 to April 12 at Humber Galleries North Space in Toronto.

Camille Georgeson-Usher is a Coast Salish/Sahtu Dene/Scottish artist, scholar and writer from Galiano Island, of the Penelakut Nation. In addition to being programs coordinator at the Inuit Art Foundation, she is currently a PhD candidate in cultural studies at Queen’s University, where she will be telling a story of Indigenous arts collectives activating public spaces through gestures both little and big.

Asinnajaq, also known as Isabella Rose Weetaluktuk, is a visual artist, filmmaker and writer. She also curated a program celebrating 30 years of Inuit film at the most recent edition of ImagineNATIVE.

Asinnajaq, also known as Isabella Rose Weetaluktuk, is a visual artist, filmmaker and writer. She also curated a program celebrating 30 years of Inuit film at the most recent edition of ImagineNATIVE.