When researcher Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández released a report last week showing that students entering Grade 9 at Toronto’s arts high schools are more than twice as likely to be white—and nearly twice as likely to come from a wealthy family—than students at other Toronto public schools, he hoped the findings would spark interest.

But even he and study co-author Gillian Parekh didn’t realize just how much conversation would flow from these findings.

News stories in Metro, the Toronto Star and NOW were shared widely on social media. And it was less than a day before Toronto District School Board trustee Parthi Kandavel demanded that the board review its admissions policies for its specialized arts high schools.

For all the immediate impact of his findings around privilege and arts education, however, Gaztambide-Fernández says the really big challenge on his mind right now is how to keep this conversation going in the days, weeks and months ahead.

“I think that engaging in the conversation is really important, and making sure the conversation doesn’t go away,” Gaztambide-Fernández tells Canadian Art in a phone interview from his office at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, where is he acting head for the Centre for Urban Schooling. “I know that I’m even surprised by the amount of reaction this has caused—but it’s something that can fizzle just as fast.”

And this conversation around racial and class privilege in early arts education—like the problem it addresses—shouldn’t just be restricted to Toronto, he says.

“I think these findings are really consistent with what we are finding in other Canadian cities,” Gaztambide-Fernández states.

There are myriad implications of Gaztambide-Fernández’s findings that members of the arts community might not consider at first glance. For instance, the results put the lie to the notion that publicly funded arts high schools are actually serving the whole city. They also suggest that “these programs are used by parents who have a lot of privilege to create a kind of self-segregated space for families with privilege.”

“Students [in the specialized arts high schools] come from so few middle schools,” says Gaztambide-Fernández. “We had a hunch that people weren’t coming from all over the city. But we didn’t think the schools they were coming from would be so similar in terms of race and class, which suggests a process of streaming that starts much earlier in the school process.”

Part of the result is that “we need to have a very serious discussion about how we want to spend our resources,” says Gaztambide-Fernández. “Do we want to spend them to enhance the education of a very few people? Or to ensure that more people have access?”

Another implication of the study is that we need to discuss what types of art forms are currently designated as worthy of study in Canada’s public schools—and whether these forms actually reflect the diversity of Canada’s cities.

“Do we still want to insist students be playing tuba and violin” for music, or “learning painting” for visual art, for instance? Or should public schools be open to “teaching how to DJ and how to make music on computers? Should we be teaching graphic design? Should we be teaching students about dance traditions that are not ballet-focused?”

Some arts high schools in the US, Gaztambide-Fernández notes, have had success when they broadened the types of art forms they were willing to teach or encourage, and made explicit efforts to recruit from “majority minority” middle schools.

But in Toronto and many other parts of Canada, those efforts are still nascent at best.

In some US arts high schools, for example, students can have graffiti in their application portfolio, and pursue it in their coursework. But “that is unlikely to happen in Toronto” at the moment, says Gaztambide-Fernández.

Ultimately, says Gaztambide-Fernández, we need to keep asking questions about “what kind of arts education is happening in local schools that are not arts high schools, and why there is not more opportunity for students who don’t have that kind of access.”

He also wants to squarely refute the claims some online and offline commenters have made—namely, that the cause for this racial and class disparity is “maybe parents of colour and immigrants just don’t value the arts.”

“I say, go to a powwow and tell me the people there don’t care about the value of cultural traditions. Go to the Chinese New Year celebrations in Markham and tell me those people don’t care about the arts. Or go to the Latin festivals [like Inti Raymi] in Christie Pits and tell me those people don’t care about culture,” Gaztambide-Fernández argues. “They care about cultural life, and they would very much like their families to be part of it.”

Yet “if we don’t talk about it,” Gaztambide-Fernández reminds, “these things will go unrecognized.”

The full text of the study, titled “Market ‘Choices’ or Structured Pathways? How Specialized Arts Education Contributes to the Reproduction of Inequality” is available on the website of Education Policy Analysis Archives.

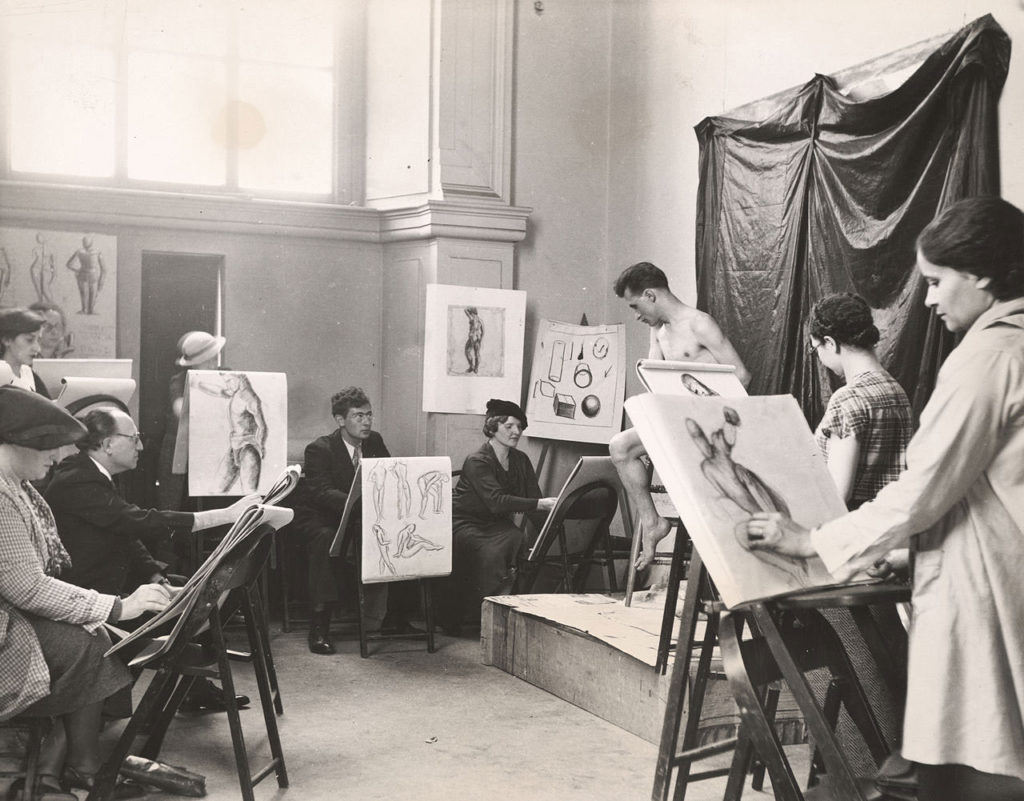

Classical ideals have long been at the core of North American arts education, as demonstrated by this photo of a life drawing class at the Brooklyn Museum in 1935. Now, a Toronto-based researcher is asking whether an emphasis such forms really reflects the diversity needed of arts education today. Photo: Archives of American Art via

Classical ideals have long been at the core of North American arts education, as demonstrated by this photo of a life drawing class at the Brooklyn Museum in 1935. Now, a Toronto-based researcher is asking whether an emphasis such forms really reflects the diversity needed of arts education today. Photo: Archives of American Art via