$34,820. That’s a figure that wasn’t trumpeted much in Canada’s fall auction roundups last week. But it’s an important number to April Britski, executive director of CARFAC National in Ottawa, as she reflects on those auction results.

Why? Because $34,820 is how much revered Inuit artist Kenojuak Ashevak, and her estate, would have received from auction sales had the Artist Resale Right been implemented back in 2012, the last time such legislation was possible. Already effective in more than 90 nations worldwide, the Artist Resale Right gives artists, or their estates, a small percentage of secondary market sales. But Canada doesn’t yet have it, and artists are continuing to lose out.

“We see several artists coming to auction again and again,” says Britski in an email. “Sometimes even the same artwork gets resold numerous times, with the value continuing to grow.” Britski points out that last week, one of Ashevak’s Enchanted Owl prints went for a record price of four times more than similar prints had gone for before—and more than any other Canadian print had ever gone for before at auction.

“Many people profit from [Ashevak]’s work,” Britski argues. “What we’re asking for is a small fraction of what everyone else gets paid from the work she created. Since 2012, when the ARR could have been implemented, 180 of her works have sold through 13 auction houses in Canada and abroad, totalling $696,405. More than half her works sell for $1,000 to $2,000 each, while others sell for much more. Had ARR been legislated in 2012, she and her estate would have received $34,820 in royalties. This is minimal compared to what the seller and auction house were paid on those sales, and it does not even include sales through commercial galleries.”

Artist Mary Pratt, who passed away in August of this year, also had a painting go for a record price at last week’s auctions. Her estate received nothing from the sale, even though she had been an advocate of the ARR in Canada during her lifetime. Britski notes, “Mary Pratt especially…[was] disappointed to know it was unlikely to be legislated in her lifetime.”

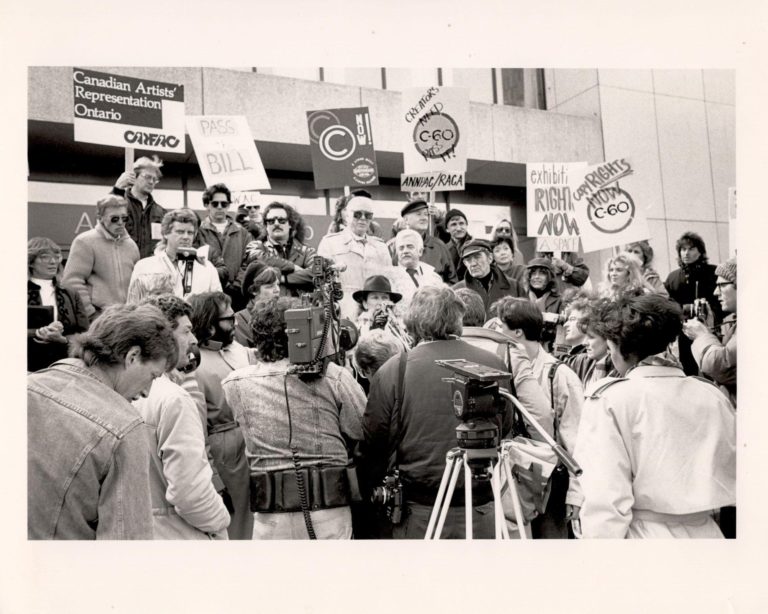

CARFAC has been advocating for improved artist compensation for decades. Here, a CARFAC protest on copyright fees and exhibition fees outside the Art Gallery of Ontario in 1988. Photo: Facebook / CARFAC.

CARFAC has been advocating for improved artist compensation for decades. Here, a CARFAC protest on copyright fees and exhibition fees outside the Art Gallery of Ontario in 1988. Photo: Facebook / CARFAC.

The late Kenojuak Ashevak was so revered that a Heritage Minute was made about her. This is a still from that film. But CARFAC remains concerned that her estate still receives no resale right from increasing secondary market sales of her art. Image: Historica Canada.

The late Kenojuak Ashevak was so revered that a Heritage Minute was made about her. This is a still from that film. But CARFAC remains concerned that her estate still receives no resale right from increasing secondary market sales of her art. Image: Historica Canada.

Britki’s reflections on Artist Resale Right losses are just one way that some people in Canada’s art scene have been parsing fall auction results—beyond the big-sales highlights—in recent days. Indeed, while some lament the lack of artist compensation, others observe how a few less-than-ideal sale prices could indicate some slowdown of market momentum this fall.

Montreal artist and art consultant Courtney Clinton, for one, believes that some works by Lawren Harris, A.J. Casson and Arthur Lismer—particularly those that veered away from classic forested landscapes—performed worse than expected at Canada’s fall auctions. She points out that Lismer’s Tugs and Troop Carrier, Halifax Harbour (1921), which was on the cover of the Heffel Canadian Impressionist and Modern Art catalogue, was hammered down slightly below its low estimate. A.J. Casson’s The Village Mill (1937) was also hammered down for just above its low estimate. And while a few of Harris’s popular mountain scenes did well, his Water Tower (1919) went on the low end of estimate at Waddington’s.

“I’m not saying these artists aren’t doing well,” says Clinton, “but I think there was a hope [their markets] could branch out beyond landscapes and it just didn’t perform that way.”

Toronto curator, art consultant and private dealer Chris Varley also had concerns about some of what he saw in last week’s auctions—particularly around certain works coming to auction again after a few years.

“A number of auction retreads popped up at Heffel, especially Group of Seven,” said Varley. In Varley’s opinion, returns on those retreads were generally weak. For instance, A.J. Casson’s 1955 Village Church at Barry’s Bay was sold by Heffel back in 2000. Last week, it was hammered down below its low estimate. J.E.H. MacDonald’s The Swamp, Algonquin Park (1951) had previously been sold by Heffel in 2000 and 2013. Last week, it was also hammered down around its low estimate.

Varley also had a concern that the most exciting highs at auction last week did not indicate sustainable trends. The biggest story was that the 1925 Frederick Banting painting The Lab went for ten times its low estimate at Heffel, “but that painting will never appear again,” said Varley, and much of its value was tied up in the fact that it was a painting of the very lab where Banting co-discovered insulin. (Banting’s other paintings tend to focus on other subject matter, and given that he was also a scientist, he produced fewer canvases than professional artists of the period.)

Both Varley and Clinton were also watching to see whether the current interest around Peter Clapham Sheppard, subject of a new book by Tom Smart and PR push by collector Peter Gagliardi this fall, will be continue through the 2019 auction seasons and beyond. Sheppard’s Elizabeth Street (ca. 1930s) went for four times its estimate, setting a world record at Waddington’s last week.

Clinton reflects that “the biggest trend I see right now is looking around the Group of Seven era to find other actors that could be interesting,” Sheppard included. Varley believes “there are a lot of other artists who deserve the same attention [as Sheppard], but they haven’t had it yet.”

But just how those artists or their estates might benefit from such attention continues to define, at least for April Britski and CARFAC, conversations around secondary market sales in Canada. Market trends aside, artists themselves largely remain excluded from auction-world exchanges in Canada.

So will next year’s auctions offer a resale right opportunity at last? How will such legislation bear on secondary market prices? It’s hard to tell. The House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage is currently studying renumeration models for artists and creative industries, and is expected to issue recommendations in coming months, possibly including implementation of the ARR in Canada.

“The Finance Committee recommended in 2017 that the Copyright Act include it too,” says Britski of the Artist Resale Right. “The question is: What can be accomplished before the federal election?”

The sale of Frederick Banting’s The Lab at more than ten times its low estimate at Heffel was one of the biggest stories at Canada's fall 2018 auctions. But some observers wonder if those high numbers are trend that can truly be sustained. Photo: Heffel.

The sale of Frederick Banting’s The Lab at more than ten times its low estimate at Heffel was one of the biggest stories at Canada's fall 2018 auctions. But some observers wonder if those high numbers are trend that can truly be sustained. Photo: Heffel.