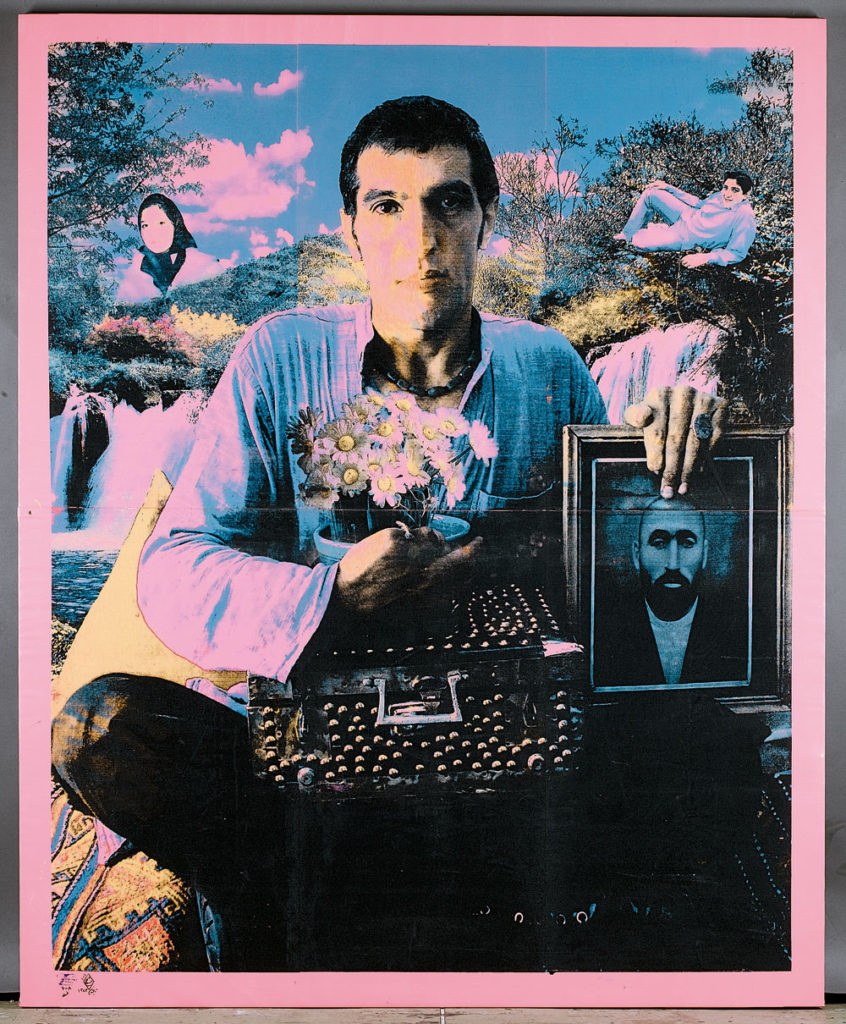

At the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, there is a newly installed, wall-sized canvas of a man rendered in pretty shades of pink and blue. The man holds a bouquet of flowers in one hand, while in the other, he holds a photograph of his father, whose visage is dignified and solemn. In the background, there are trees and clouds, a lake and a waterfall, a sanguine son and an elegant daughter.

Attached to this man’s portrait is a large paper tag. It reads, in black and white, TERRORIST.

This self-portrait, created by Iranian artist Khosrow Hassanzadeh, was actually made 13 years ago, in 2004.

But like many of the other works in “Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet,” a rare survey of contemporary Iranian art debuting this weekend at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, Terrorist: Khosrow speaks with renewed power in the context of the current US ban on travellers from seven Muslim-majority countries—Iran included.

“Hostility from the West has been ongoing,” says exhibition curator Fereshteh Daftari, but “sometimes it is highlighted, and in some ways, it makes the works come alive.”

Collector Mohammed Afkhami, whose “mini-archive of Iranian art” (it’s actually 300-plus works accrued over 12 years so far) serves as the well from which the 23 works in the show were drawn, agrees that the current political conditions may “reinvigorate” the way these artworks may be received.

“What happens is if there is another period where relations become increasingly adversarial between the West and Iran…the work becomes more charged, more meaningful, more thoughtful,” Afkhami says.

Ali Banisadr’s large oil painting We Haven’t Landed on Earth Yet (2012) is influenced by the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch and Persian manuscript paintings alike. The imagery is also impacted by Banisadr’s childhood memories of the Iran-Iraq War. © Ali Banisadr. Courtesy Mohammed Afkhami Foundation.

Ali Banisadr’s large oil painting We Haven’t Landed on Earth Yet (2012) is influenced by the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch and Persian manuscript paintings alike. The imagery is also impacted by Banisadr’s childhood memories of the Iran-Iraq War. © Ali Banisadr. Courtesy Mohammed Afkhami Foundation.

But there are many downsides of the US travel ban, of course, ones that both Afkhami and Daftari understand intimately.

The Art Newspaper has reported that least two of the artists slated to attend the opening of “Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet” have cancelled travel to Toronto. They are Iranian artists currently based in the US, and are scared to leave for fear of not being able to get back in.

“I am stuck here,” artist Shahpour Pouyan told the New York Times in an email. “I can’t leave the country and as an artist it means I can’t make shows and present my works internationally…. This is such a mess.”

It is also uncertain how the US travel ban may impact the movement of Afkhami and Daftari as they continue their own work—which includes trying to finalize a tour of “Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet” to art institutions in Texas and the East Coast.

Daftari, formerly a curator at New York’s MoMA, has worked in the US “continuously since 1988,” and prior to that, she was studying art history there.

“I’ve lived in the States more than I’ve lived in any other country,” Daftari says.

Afkhami, who works in finance, studied at the University of Pennsylvania (where he has endowed a scholarship) and is based in Dubai. He planned to return to the States next week, and he has received advice that he should be able to enter given that he is a British national with a US visa on that passport.

But, Afkhami says, “the proof will be in the pudding when you try to enter.”

Shirin Aliabadi’s Miss Hybrid 3 (2008) plays on the ways that some Iranian women push boundaries of expected appearance by dying hair blonde, wearing blue contacts and getting nose jobs. © Shirin Aliabadi. Courtesy Mohammed Afkhami Foundation.

Shirin Aliabadi’s Miss Hybrid 3 (2008) plays on the ways that some Iranian women push boundaries of expected appearance by dying hair blonde, wearing blue contacts and getting nose jobs. © Shirin Aliabadi. Courtesy Mohammed Afkhami Foundation.

The fact is, Iranian artists, curators and collectors have had to navigate and subvert restrictions, borders and conflict (armed and otherwise) at home and abroad for many years. (Many Iranians prefer to call themselves Persian, for instance, a fact recognized in the subtitle of this Aga Khan Museum exhibition—“Contemporary Persians.”)

So it is not surprising, perhaps, that two works expressing intimate knowledge of war, camouflage and propaganda are placed prominently at the entrance of “Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet.”

Shiva Ahmadi’s Oil Barrel #13 (2010) appears at first to be a life-sized oil barrel intricately decorated with classical Persian motifs. Only when one looks closely can one see that some of the designs appear to be gaping wounds, while others resemble decapitated animals. It’s imagery influenced by Ahmadi’s 1980s childhood memories of visiting Iran-Iraq War victims alongside her medic mother.

Mahmoud Bakhshi’s Tulips Rise from the Blood of the Nation’s Youth (2008) is a bright-red neon piece that plays on the emblem of Iran—a tulip shape that evokes the flower’s status as symbol for martyrdom.

While to some, Bakhshi’s red, glowing tulips—they can spin at different speeds, if desired—might recall a shop sign, or a discotheque, they can evoke something else entirely.

“In Iran in the 1980s during the Iran-Iraq War, it was basically the bloodiest war since the Second World War—about a million and a half deaths,” Mohammed Afkhami says. “The whole rallying cry to the country was about revering the martyrs, the people who lost their lives—and if you went to public fountains all over Iran, they tinted the water red.”

Mahmoud Bakhshi’s Tulips Rise from the Blood of the Nation’s Youth (2008) at the Aga Khan Museum. The tin-and-neon work, drawn from the collection of Mohammed Afkhami, can be read in several ways relating to Iran’s history. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Mahmoud Bakhshi’s Tulips Rise from the Blood of the Nation’s Youth (2008) at the Aga Khan Museum. The tin-and-neon work, drawn from the collection of Mohammed Afkhami, can be read in several ways relating to Iran’s history. Photo: Leah Sandals.

Ultimately, the US travel ban is bad not only for Iranian artists, but the public at large in the United States and elsewhere, Afkhami says.

The ban comes on the heels of few recent years of increasing connections between Iranian artists in US audiences. The year of 2015 was a particular high point given Monir Farmanfarmaian’s Guggenheim retrospective, Shirin Neshat’s Hirschhorn survey and Parviz Tanavoli’s first major US retrospective at the Davis Museum. (Works by all three of these artists are in the Aga Khan show, with Farmanfarmaian’s dazzling, and unexpectedly figurative, mirror work a particular standout.)

“If anything, these artists serve as a very important bridge to create some commonality, some understanding,” Afkhami argues.

This message of commonality is echoed by the final piece in the show—Morteza Ahmadvand’s Becoming (2015), which shows a Christian cross, a Jewish Star of David and an Islamic Kabba morphing into three perfect spheres.

“We are all one planet,” curator Feresh Daftari observes. “There should be unity, and not divisiveness.”

In Morteza Ahmadvand’s video installation and sculpture Becoming (2015), a Jewish Star of David, Christian cross and Islamic Kabba morph into a perfect sphere. © Morteza Ahmadvand. Photo: Mehdi Zahmatkesh. Courtesy Mohammed Afkhami Foundation.

In Morteza Ahmadvand’s video installation and sculpture Becoming (2015), a Jewish Star of David, Christian cross and Islamic Kabba morph into a perfect sphere. © Morteza Ahmadvand. Photo: Mehdi Zahmatkesh. Courtesy Mohammed Afkhami Foundation.

But can art really move the needle on the political front? Afkhami says yes—with conditions.

“It’s not going to directly shape or impact politicians, especially in this era, where things are going to extremes everywhere,” Afkhami says. “However, where the narrative does change is that extremism is fuelled by people.”

If people can look at an artwork from a country “that is supposedly bad, where the people are ‘nothing like us’ and say, ‘Oh, I relate to this work,’ it narrows that divide,” Afkhami hopes.

“All you are trying to do is soften people’s preconditioned views—that’s a win today,” Afkhami says. “So the bar is set low. I think that’s the realistic objective.”

“Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet: Contemporary Persians” will be on exhibit at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto from February 4 until June 4.

Khosrow Hassanzadeh,

Terrorist: Khosrow,

2004. Acrylic and silkscreen ink on canvas. © Khosrow Hassanzadeh. Courtesy: Mohammed Afkhami Foundation.

Khosrow Hassanzadeh,

Terrorist: Khosrow,

2004. Acrylic and silkscreen ink on canvas. © Khosrow Hassanzadeh. Courtesy: Mohammed Afkhami Foundation.