Allen Ginsberg. A train accident. Intergenerational trauma.

Aspects of all of these elements will converge in Geoffrey Farmer’s upcoming project at the Venice Biennale’s Canada Pavilion, according to details recently released to the media.

A major impetus for the project comes from two photographs forwarded to the artist by his sister in April 2016. Farmer states the impact, and consequent trajectory, of these photos as follows:

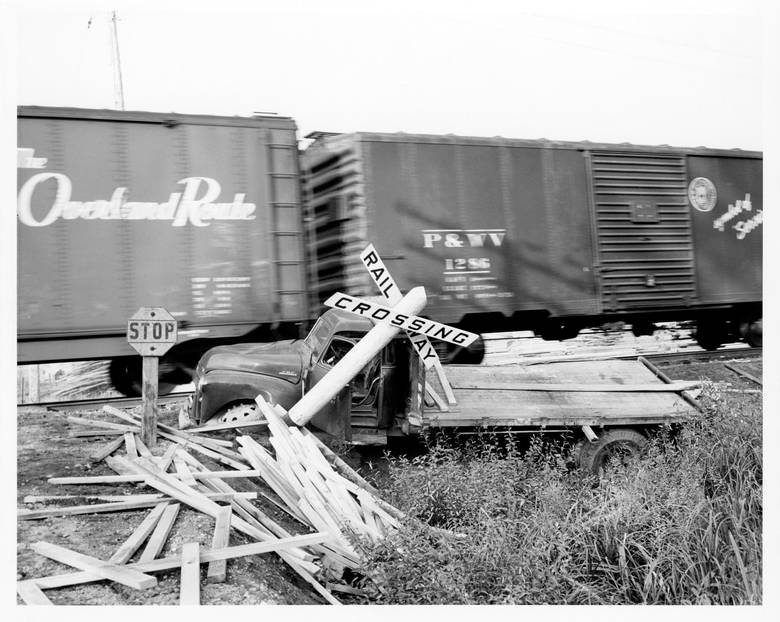

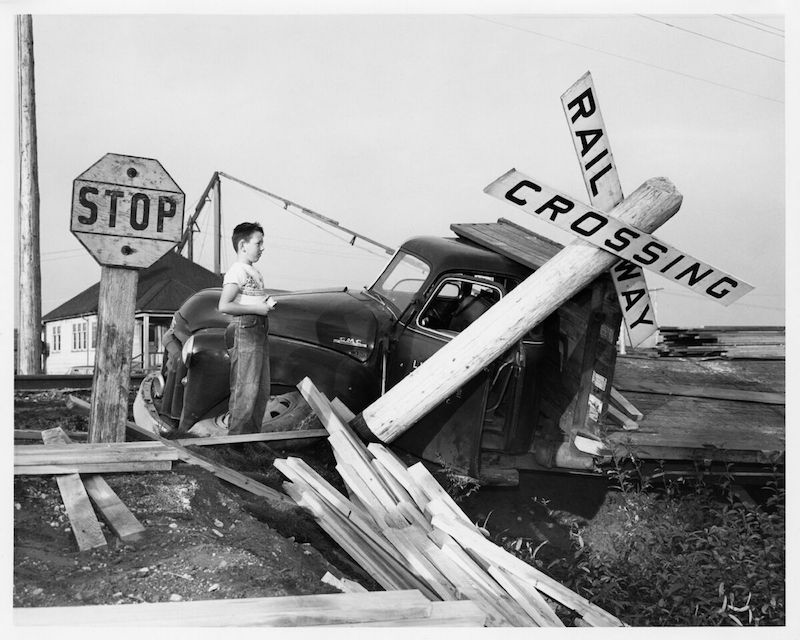

The story of my project for Venice begins with these unpublished press photographs from 1955. They depict a collision between a train and a lumber truck halted by a railway crossing sign. There are planks scattered across the foreground and in one of the images, an unidentified boy poses with a half-eaten apple looking stiffly towards the horizon.

I was holding a copy of Howl, the epic poem by Allen Ginsberg, at the time I received the photographs. I was in my studio reading about the San Francisco Art Institute students who had organized the poem’s first reading on 7 October 1955. I had been an SFAI student myself in 1991. I was 24 years old and I heard Ginsberg sing Father Death Blues, which rattled me. It was also when I first learned about the Venice Biennale. I discovered a copy of a 1970 artscanada magazine about Michael Snow in the school’s library. I somehow thought that if I went back to that moment of discovery I might find something. I found Allen Ginsberg and the memory of a poem he recited.

I mention all of this because the absent figure in the photographs, beside the photographer, is my grandfather Victor, who walked away from the accident only to die a few months later. But I never knew that, or anything about the accident, or anything about him, until these images arrived in my inbox, sent to me by my sister Elizabeth, on 14 April 2016 at 6:24PM.

But this isn’t entirely true. I somehow knew the photographs intimately; the impact of the collision had been passed down through my family without us being aware of it. A shape created by absence, by rage, by unspoken trauma and grief.

They have been waiting patiently for 62 years, for the opportunity to fulfill their destiny, to break a spell, to open a space and to help me find a way out of the mirror.

Unknown photographer (Collision), 1955. Archives of the artist. Courtesy CNW Group/National Gallery of Canada.

Unknown photographer (Collision), 1955. Archives of the artist. Courtesy CNW Group/National Gallery of Canada.

Appropriately, Farmer’s show at the Canada Pavilion in Venice will be titled “A way out of the mirror,” borrowing from Ginsberg’s poem Laughing Gas, which reads, “A way out of the mirror / was found by the image / that realized its existence / was only… / a stranger completely like myself.”

The architecture of the Canada Pavilion will also be impacted by Farmer’s project.

“In his Venice project, Geoffrey once again finds a world enclosed inside an image and an image giving rise to a world,” explained Art Gallery of Ontario curator Kitty Scott, who is curating Farmer’s Venice project. “Personal memory and familial history flow into a broader stream of reflections on inheritance, trauma, and desire. The pavilion itself, colliding with the artwork, is transformed, opening to the outside as its architecture is reimagined in the guise of a fountain.”

Farmer was born in 1967 in Vancouver where he continues to live and work. Since his first show in 1997 and throughout his 20-year career, his work has earned critical acclaim.

Farmer has also produced a special Venice-related artist project for the Spring 2017 issue of Canadian Art. One element, available only to subscribers, is a flexidisc containing a recording produced by Farmer and Toronto duo Life of a Craphead. Another element, available to all readers, is a collage-based foldout and annotated narrative.

Unknown photographer (collision), 1955. Archives of the artist. Courtesy CNW Group/National Gallery of Canada.

Unknown photographer (collision), 1955. Archives of the artist. Courtesy CNW Group/National Gallery of Canada.