An Ontario Court of Appeal decision, released September 3, ruled that Maslak-McLeod Gallery of Toronto had breached a contract with art collector Kevin Hearn when it sold him a Norval Morrisseau painting with unreliable—and likely false—provenance documents.

Though the decision did not say the painting Hearn purchased was an outright forgery or fake, the appeal judges did say it mattered that the provenance was false. In this, they differed from a trial judge last year who had decided in the art dealer’s favour.

“The trial judge erred in failing to find that the Gallery’s provision of a valid provenance statement was a term of the purchase and a warranty, not mere puffery,” the new appeal decision states.

“Mr. McLeod’s assertion that the painting was genuine was only matched by his elusiveness in demonstrating that fact, which can only be explained as deliberate,” said the appeal panel. “With respect to the provenance statement, Mr. McLeod made a false representation, either knowing that it was false and without an honest belief in its truth, or he made the statement recklessly without caring whether it was true or false, with the intent that Mr. Hearn would rely upon it, which he did, to his personal loss.”

Though gallery owner Joseph McLeod is no longer alive, McLeod’s estate has been ordered to pay Hearn $50,000 for breach of contract and breach of the Sale of Goods Act, plus punitive damages of $10,000.

Hearn, who is also a musician with the band the Barenaked Ladies, said the whole experience has made him much more cautious about purchasing art, or even visiting art galleries.

“I thought the music business was corrupt,” Hearn tells Canadian Art. “But it’s got nothing on the art world.”

Implications for Art Dealers—and Buyers

“I would describe this decision as a big warning to art dealers,” says Jonathan Sommer, the lawyer who represented Hearn in court at the initial trial. (Matt Fleming and Chloe Snider of Dentons LLP represented Hearn during the appeal.) “What the court of appeal has said is that accurate provenance is one of those things that for the art world is extremely important.”

To be clear, Sommer adds, “If the potential purchaser of a painting comes in and asks for provenance,” Sommer adds, “you better make sure it’s right or you could end up like McLeod did here, being liable for civil fraud—which will not only cost you your money but cost you your reputation too.”

Alternatively, if complete provenance or guarantees of authenticity are not available, art dealers must be clear about that, using language such as “attributed to” and also being willing to reduce prices significantly.

At the same time, Sommer is clear about art buyers’ need to be vigilant about what’s on offer: “I will always advise people to get dealers to put their money where their mouth is, with full provenance statements and guarantees of authenticity—or no sale.”

Hearn, for his part, allows that he has met reputable and trustworthy art dealers before—but McLeod was not one of them, a fact he became aware off all too late.

“Joe really seemed like a nice guy when I met him,” Hearn says. “But he fooled me.”

Judges Are Not Art Experts, Appeal Notes

The Court of Appeal panel also found that the judge in the original decision erred, in part, by trying to become an art expert himself. And he especially erred in not presenting his own art-theory and art-historical research as part of evidence, or permitting expert witnesses to respond to his critiques.

Art historian Carmen Robertson, who has studied Morrisseau’s works, had testified in the original trial that the signature on the back of the work Hearn purchased is “not representative of the works that I have observed in art museums from Canada, in important private collections” related to Morrisseau. Robertson also testified that based on her analysis of the painting, it was not a genuine Morrisseau.

“The trial judge rejected Professor Robertson’s expert evidence on a contrary theory that was not put to her and on which she was not cross-examined,” wrote the appeal court judges in their decision. They added: “The trial judge stepped out of the impartiality of his position as trial judge and descended into the arena, effectively becoming an art expert posed against Professor Robertson…. This was not appropriate.”

Asked about this judge’s error, Sommer says that people do sometimes underestimate the expertise required to evaluate an artwork.

“Connoisseurship is something that, like many forms of expertise, is not appreciated by those who are not connoisseurs,” says Sommer. “Because you can’t see what you don’t know. It becomes an unknown unknown to a lot of people.

“I think that a lot of people—and judges are people too—may sometimes think that they are as in as good a position as someone who has studied a particular artist or art form to judge it, because it’s just this ‘thing’ in front of you on a piece of canvas. And yet the more you know about art, the more you know that it’s an incredibly complex thing.”

Ontario Case Bound to Resonate Nationally

François Le Moine is a Montreal lawyer who specializes in art and cultural heritage matters. He also teaches graduate courses about art law, and he says that this case decision is one that he will be adding to his teaching resources as soon as possible.

“Definitely it is quite a significant decision,” says Le Moine, because in it, “the court clearly says that the provenance that is provided to a buyer is a term of the contract.” The implications are “in no uncertain terms that …. if an [art] buyer receives a provenance that is not accurate, they will be able to obtain a legal remedy,” Le Moine explains. That was not always the case in the past.

Even though this case was decided in a provincial court, its implications are bound to resonate across the country, Le Moine believes.

“This means a lot when said by the highest court of Ontario,” says Le Moine. “This is something that could help to get different actors of the art market to be more responsible and transparent.”

There are also links to consumer protection and the health of the art market in general, Le Moine suggests.

“When you walk into a gallery you don’t always know what you are getting yourself into,” Le Moine says. “It’s important that the law is there to protect buyers, so that we can encourage the public to buy more works by Canadian artists.”

Reclaiming a Legacy

Another way the case may resonate nationally is that it, and a related documentary out this year called There Are No Fakes, has the potential to bring forward other legal cases related to Morrisseau forgeries in particular: “That wouldn’t surprise me at all,” Sommer says. “I think public awareness of this issue is at an all-time high and I have a feeling there are people who will revisit their collections and hopefully ask questions.”

Hearn hopes that the appeal’s critiques and judgments—as well as the original trial judge’s admission that there is evidence of a fraud ring and forgeries in distribution around Morrisseau’s work—help reclaim a significant artist’s legacy.

“I think Kevin went into that courtroom with me to reveal an injustice and reveal something that was an insult to Norval Morrisseau’s legacy,” Sommer says.

“At the root of [this fraud case] is a disrespect to a great artist,” Hearn confirms. “Norval Morrisseau was a great artist, and he deserves better.”

A correction was made to this article on September 5, 2019. The original copy failed to state clearly that Matt Fleming and Chloe Snider of Dentons LLP represented Kevin Hearn at the appeal. The original copy had stated that lawyer Jonathan Sommer represented Hearn “in court,” by which was meant, but not clearly stated, that Sommer represented Hearn in court at the initial trial only. This error was solely Canadian Art’s, and we regret any confusion it may have caused.

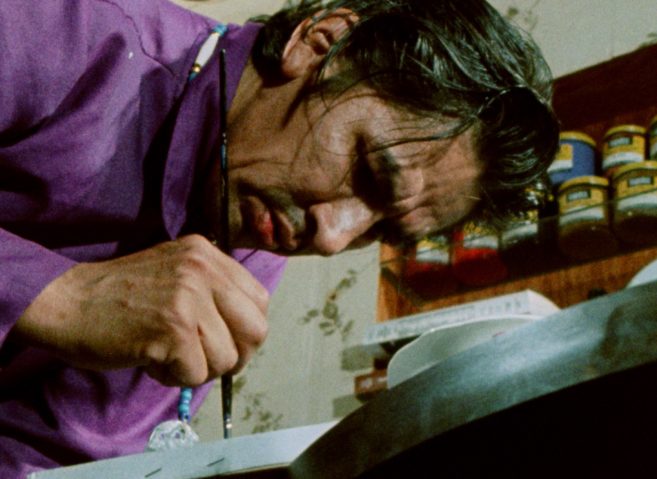

Art dealer Donald Robinson of Kinsman Robinson galleries examines the painting at the centre of a Norval Morrisseau forgeries case in a scene from the new documentary There Are No Fakes.

Art dealer Donald Robinson of Kinsman Robinson galleries examines the painting at the centre of a Norval Morrisseau forgeries case in a scene from the new documentary There Are No Fakes.