Recent controversies over public art in Calgary have led to a funding rollback by the City, as well as other changes to its public-art process.

On May 26, City Council voted to approve multiple changes to Calgary’s public art program.

Notably, Calgary’s “1% for art” guideline—a common practice in many North American cities that advocates allocation of 1 per cent of certain kinds of civic spending to public art—was changed.

Now, in Calgary, the 1 per cent target will remain in place for all capital projects worth up to $50 million. Above $50 million, 0.5 per cent will be dedicated to public art, with a cap imposed at $4 million for public art related to any given capital project.

Councillor Brian Pincott—one of the few who voted against the funding reduction and cap—says it’s a disappointing decision for public art in Calgary, and that it makes little sense given the city’s renewed focus on culture.

“We just developed a new citywide arts strategy called Living A Creative Life,” Pincott says. “We have this policy that council supported unanimously, and then we come along and we pull public art out of it….we have to be able to follow through with these bold policy statements with actually being committed on the ground.”

Pincott—who prior to his career in politics worked as a lighting designer in the arts sector—also says the council’s decision sends a bad message about support for the arts in the city in general.

“This doesn’t directly put any funding to arts and culture organizations in jeopardy,” Pincott admits, “But it is a softening of commitment to the arts and culture in our city.”

Yet advocates for the changes say their concern wasn’t necessarily art, just financial efficacy.

“I don’t want to kill the [public art] program; I just want to ensure we get value for money,” says Councillor Shane Keating, who pushed for a review of the city’s public art policies and voted for the changes.

“I think we had a system which I wouldn’t say was flawed, but it lacked some general public oversight,” Keating says. “And therefore we had an outcry from the taxpayers—‘How are you using our money?’”

Key “Blue Ring” Controversy Took Hold During Election

The council’s May vote was based on a public-art policy review requested after multiple public-art controversies of late in the Alberta city.

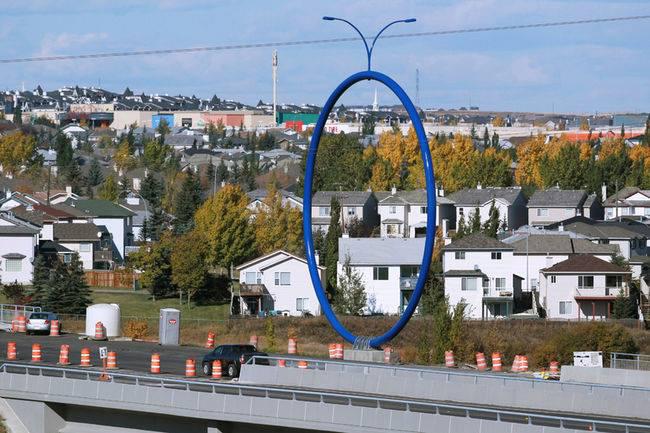

Most notable of these controversies was the public outcry around Travelling Light, a large blue ring created by European collective Inges Idee that was unveiled in October 2013.

Even Mayor Naheed Nenshi called Travelling Light and its $470,000 price tag “awful.” The controversy also gained traction on social media, with a spoof Twitter account springing up on behalf of the artwork itself.

Councillor Pincott attributes much of the outcry around Travelling Light to timing.

Many public artworks have generated negative feedback, Pincott admits, but “the difference here is hue and cry—[it] was installed during an election campaign and so it became a lightning rod for public art and waste of public dollars.”

“If you look at public art in a whole bunch of cities, some of the most controversial installations have turned into iconic installations for those cities,” Pincott also argues.

As an example, Pincott points to Family of Man, a group of tall, elongated, naked figures that generated outrage when it was installed in 1967. Since then, Mario Armengol’s statues have become a Calgary landmark, with their silhouette adopted as the logo of the Calgary Board of Education.

Yet Travelling Light wasn’t the only factor at hand in Calgary’s recent policy decisions.

Also key was the revelation that the $1.4-billion West LRT—the largest infrastructure endeavour ever undertaken by the City of Calgary—failed to include public art in its budget. Under the prior guidelines, the LRT project should have allocated roughly $8 million to public art, and when the error was discovered in 2012, councillors did find $3.5 million for public art, but no more—it already seemed a challenge to find that funding given the LRT’s other multi-million-dollar cost overruns. Under the new guidelines voted in in May, the West LRT’s public art allocation is capped at $4 million.

Councillor Shane Keating says he has also heard concerns from residents about Beverly Pepper’s Hawk Hill Calgary Sentinels in Ralph Klein Park, a set of landscaped pyramids and monoliths with a cost of $1.57 million.

More Public Feedback Required Moving Forward

Calgary’s new guidelines also require the public art process to integrate more feedback from the public.

In the past, public art decisions in Calgary were made by a 5-person jury consisting of 3 people involved in the arts, 1 person from the business unit of the capital project involved, and 1 community member—a process considered best practice in many other cities.

Moving forward, public-art decisions will be made by a 7-person jury—3 people involved in the arts, 1 from the business unit, and 3 community members.

Not everyone agrees with the changes.

“Leave the decisions to the experts, in my mind,” says Ken Heinbecker, VP of marketing at Heavy Industries. Heavy Industries is a Calgary company which often helps with fabrication on local, national and international public art projects—including on the much-critiqued Travelling Light.

But Sarah Iley, manager of culture at the City of Calgary, says people feel differently about art in the public realm than they do about art in publicly funded galleries, and it’s good that the change in guidelines reflects that.

“I think when you are talking about using dollars in the public realm, there is a different lens than if you were an acquisition committee for an art gallery—even if you were an acquisition committee for a public art gallery.” Iley says. “Because the sense is, ‘That’s my park—I walk through there all the time.’ There’s a very different sense of ownership in public space.”

Under the new guidelines, artists will also be requested to provide information on public engagement in their proposals, while more public feedback is to be solicited online and in person in regard to upcoming projects.

Iley says that if there is one thing she has learned from recent events, it is that increased communication with the public is key.

“I think the most important thing [that came out of this] is that it’s hugely important to communicate with the public on an ongoing basis about what we’re trying to accomplish with public art,” Iley says. “And I think that the more engaged people are, the more informed they are.”

Pooling of Funds Another New Measure

Another new change under Calgary’s public art guidelines is the opportunity to pool funds from different capital projects into art projects elsewhere in the community.

Previously, public art funded by a given capital project had to be installed quite close to that capital project—whether that was a remote sewage plant or a suburban highway.

This measure “enables us to pool multiples of those $4 millions [(the capped public-art amount per project)] if we wanted to invest in a really, really major piece,” Iley says. “The one that people used as the example [during the policy review] was Cloud Gate in Chicago, which I think was about $23 million.”

Councillor Pincott agrees that the possibility to pool funds for works in more highly trafficked public locations is a good move—but “the value of pooling has just been taken away by the cap and the reduced percentage. Those two things [run] just totally counter to creating the value in other communities. I find that really frustrating as well.”

Wider Impact Up for Debate

Meanwhile, the impact on Calgary consultants and fabricators who work in the public art industry is yet to be seen.

“We do business all over the world, so the policy of one city—even if it is our own home city—is not the sum of our business,” Heinbecker of Heavy Industries notes.

Yet, Heinbecker says, “we are obviously disappointed [about the recent council decision] because it kind of speaks to the general consensus of the population, where people care less about art and living in a creative and dynamic city.”

However, Iley—whose division manages public art, among other cultural components of civic life—says Calgary’s cultural future is far from being in jeopardy.

“One of the things that perhaps people across the country are not aware of is that we spent $5 million on public art last year,” Iley says. “We had 25 different projects… Calgary’s doing a lot in this area.”

“Public art in Calgary is very much alive and well,” Iley contends, “And I think the fact that people want us to engage them more in its development is a positive thing. So that is the direction we are intending to go.”

A view of Travelling Light by Inges Idee—the piece of Calgary art that sparked public outcry, and then a review of public art policy in the city. Photo: via Facebook.

A view of Travelling Light by Inges Idee—the piece of Calgary art that sparked public outcry, and then a review of public art policy in the city. Photo: via Facebook.