When I call Zadie Xa, she’s running up the stairs to her studio in London, UK, where the Vancouver-born-and-raised artist has lived for the past seven years. She’s finishing her costumes for the Venice Biennale here, complexly layered patchworks of vibrant textiles and references, including forgotten goddess mythologies, Korean shamanism, marine life and the ’90s hip-hop she grew up with as a diasporic young person in Canada. Her cultural influences between spaces and locations form a strikingly personal material language.

This week, Xa and her collaborators perform at the Biennale for the first time, the largest international platform the artist has had. From May 8 to 12, Xa’s Grandmother Mago debuts on the grounds of the Venice Giardini, a work that follows from her 2016 performance at Serpentine Gallery loosely based on talchum, a Korean mask dance.

Xa’s new work continues her exploration of a fictional grandmother figure, an archetypal strong woman-slash-shaman, to carve out a relationship to her homeland.

She tells me, “Shamans sit between the living and the dead, and I think of it also as a metaphor for people who are circumnavigating the diaspora or living between different cultures or countries. Rather than thinking about the in-between as a space of uncertainty, it’s an actual solid place where new identity narratives are able to form, because we’re giving them validation and agency.”

As we continue to chat, Xa speaks about her work in the context of the Biennale, her fascination with matriarchal orcas, her views on the necessity of self-mythologizing and her favourite music.

Joy Xiang: Can you tell me more about the nature and basis of Grandmother Mago?

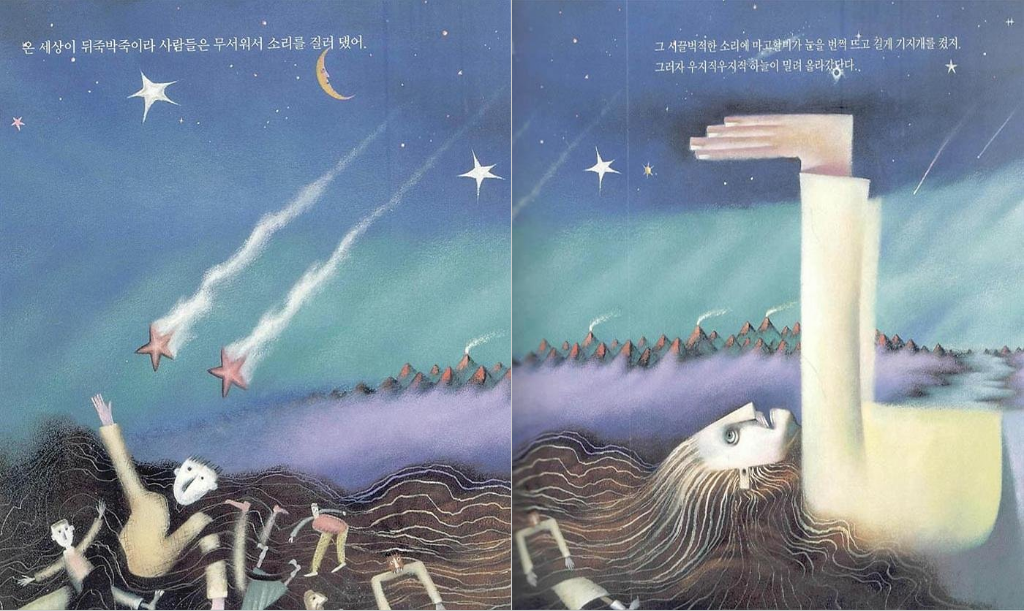

Zadie Xa: I had come across a Korean creation myth circulated through childrens’ folktales. I’m under the understanding that it was lost for a long time, because it was largely passed down orally, and when men decided to write things down, anything to do with women was completely uninteresting [to them].

The story goes that this elderly woman, a gigantic grandmother figure, created the geological formations of Korea with her excrement and urine, and by carrying big boulders to create mountains and cliff faces. It’s unsavoury in some ways if you think of it from a puritanical point of view. A giant woman using her bodily fluids to create the landmass of Korea—I just really like that image. The researcher Helen Hye-Sook Hwang has said that the Grandmother Mago figure was the original progenitor of the world, the main creator. This goddess figure birthed…eight grandchildren of different races and then they populated the world. They were considered the original shamans.

Then there’s a parallel thing I’m looking at: I spent some time in Vancouver over the Christmas holidays and really started thinking about orcas. They have strong social bonds and everything they learn about surviving is through their mom. A couple of years ago, there was an orca named Granny who died and she was the matriarch of a pod of orcas that are indigenous to Puget Sound, near Vancouver.

That’s really interesting to me, the dissemination of ancestral knowledge or survival skills through a matrilineal line. Obviously the way it’s going to translate will be different, but that’s the foundation of what I think about.

Jeong-geun, Magohalmi (children's book excerpt), 2005. Publisher: Borim Press.

Jeong-geun, Magohalmi (children's book excerpt), 2005. Publisher: Borim Press.

JX: I’m attracted to what you’ve said about the diasporic space in-between as the solid destination in itself, as a place rather than no place at all. And I think you make that a physical place, too, through your performances. Your performance at the Serpentine was disruptive, joyfully commanding and roaming. How are you working with the site of the Venice Giardini?

ZX: Venice will be very crazy because it’s the top artists in the world and it’s preview week. In the end, it’s nice because I’m trying something in those spaces without the pressure of all eyes on me—they won’t be, because it will be so hectic.

For me—if we want to put things in categorical boxes—as an Asian woman presenting works that can look ethnographic or traditional/folkloric, I’m very self-conscious about the relationship between audience consumption and performer. I’ve never wanted to put myself in a position where I felt like I would be consumed. I don’t want the performers to ever feel like they’re the hired entertainment. That’s one of the things I thought with the Serpentine: How are we able to gain control of our own agency? Rather than being consumed, how can people engage with that?

We moved around the space because we wanted people to feel like if they wanted to come with us, they needed to move. That’s what we want to do at the Giardini as well.

I’m also cognizant that within a lot of, say, homogenous cultures, traditional folk performances are used to propagate nationalism and tourism. So I’m not trying to explore my Korean background by gentrifying my placement there through essentialist ideas. It’s more about reworking and hybridity.

JX: I go back to what you’ve said in another interview about creating narratives where you’re at the centre of your own experience, and also what Victoria Sin has said about your work, “self-mythologizing as a survival tactic.”

ZX: Yeah, which is so real! Outside the idea of live performance in my work, I feel like performativity is hyper-important. I think that through that act of “lies”-making, there is a sense of dancing with ghosts, and that’s probably why I’m attracted to the idea of shamanism. It’s not, like, flirting, but kind of dancing or being in company with your ancestors through re-enactment.

“How are we able to gain control of our own agency? Rather than being consumed, how can people engage with that?”

Zadie Xa, Grandmother Mago, 2019. “Meetings On Art” public programme, Venice Biennale 2019. Courtesy Delfina Foundation. Photo: Riccardo Banfi.

Zadie Xa, Grandmother Mago, 2019. “Meetings On Art” public programme, Venice Biennale 2019. Courtesy Delfina Foundation. Photo: Riccardo Banfi.

JX: I want to touch on the overall Biennale context. The exhibition theme curated by Ralph Rugoff is “May you live in interesting times,” intended to be a wink to fake news by using a fake Chinese curse that’s been spread by Western politicians to describe a tumultuous time. The exhibition is presented as a counter-offer to that fake news. My first reaction was that this title says more about mistranslation and assumptions across cultures than about fake news, but I realized I was disturbed because—as a Chinese person who came to Canada very young—I couldn’t immediately tell if the phrase was made up.

Obviously there’s a big difference between this mass-media rhetoric that creates alienated bodies out of people and diasporic peoples actively creating their own selfhoods from fractured parts. But they both reference a malleable truth and authenticity. I’m wondering what you think about the placement of those two together and if, thinking optimistically, whether self-representation redeems that fake news aspect? Is it a counter-offer?

ZX: Within the context of the performance programme, and I would say the exhibition programme, it seems like exactly what you said: this idea of the malleability of people reworking their own realities. Like in my work, or Paul Maheke’s, or Victoria Sin’s, folks are redefining ways that specific identity narratives are told and shifted.

JX: Do you see any differences in the reception of your work in Canada and abroad?

ZX: In the London context, I feel like my work has been given a lot of space and I have a solid community. Similarly to Vancouver, there are so many different kinds of narratives around identity happening and evolving. There is some convergence where everything intersects.

One of my other goals is representing aspects of Canada in a subtle way—you know, I’ve been very homesick for the past two or three years. Thinking about orcas, such a symbol of British Columbia to me, and the idea that there’s an aspect of the Pacific Northwest coast moving in and around these Venice spaces is exciting.

JX: You’re influenced by ’90s hip-hop and rap culture, another one of the disparate elements you grew up with. Do you have any favourite music right now?

ZX: One rapper I like is Saweetie, and Megan Thee Stallion.

I still think the music I gravitate to is the music I grew up with. You cling to it because you’re attached to certain memories—Madlib, Quasimoto, A$AP Ferg.

I listen to Drake all the time because he’s also a Scorpio and Canadian. When I feel like I need to be motivated, I listen to him because he’s aggressively arrogant when he needs to be. He’s entertaining and drops all these weird colloquial Canadian things.

Zadie Xa, Grandmother Mago, 2019. “Meetings On Art” public programme, Venice Biennale 2019. Courtesy Delfina Foundation. Photo: Riccardo Banfi.

Zadie Xa, Grandmother Mago, 2019. “Meetings On Art” public programme, Venice Biennale 2019. Courtesy Delfina Foundation. Photo: Riccardo Banfi.

Zadie Xa, Grandmother Mago, 2019. “Meetings On Art” public programme, Venice Biennale 2019. Courtesy Delfina Foundation. Photo: Riccardo Banfi.

Zadie Xa’s performance is part of a series commissioned by Arts Council England. The series is co-devised by Ralph Rugoff, this year’s artistic director of the Venice Biennale, and Aaron Cezar, director of London’s Delfina Foundation.

Xa’s collaborators include Benito Mayor Vallejo, shamanic percussionist Jihye Kim and an intergenerational group of dancers: Iris Chan, Mary Feliciano, Jia-Yu Corti and Yumino Seki. For more information, visit: delfinafoundation.com/whats-on/venice-biennale-performance-programme.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Zadie Xa, Grandmother Mago, 2019. “Meetings On Art” public programme, Venice Biennale 2019. Courtesy Delfina Foundation. Photo: Riccardo Banfi.

Zadie Xa, Grandmother Mago, 2019. “Meetings On Art” public programme, Venice Biennale 2019. Courtesy Delfina Foundation. Photo: Riccardo Banfi.