Tsēmā Igharas isn’t quick to define Northwest Coast art because she’d rather let Northwest Coast art and artists speak for themselves. The belief that art can speak would likely sound romantic to non-Indigenous audiences. But Igharas—who comes from a background in Indigenous community arts and learned carving before attending art school—knows that art is a relation that Indigenous peoples visit with, not a sterile object decaying in a house of horrors such as a museum of the dead. Northwest Coast art is meant to be used and experienced; it should live and, yes, die. Editor-at-Large Lindsay Nixon interviewed Igharas on site at the Bill Reid gallery about ReMatriate’s exhibition “womxn and waterways,” perhaps the perfect space to have a conversation about where Northwest Coast art has come from, where it is now and how it will evolve. In particular, Igharas discusses the Northwest Coast women who are missing in museums, enlivened art within Indigenous feminist spaces, marginalized lesbian creation stories and ReMatriate’s work compiling an Indigenous feminist digital archive. Igharas’s assertion that any ethical archive, even a living archive, must include ongoing permissions, felt jarring—but also not. Though in some formalist circles it might be taboo to even breath such a dangerous idea in the face of non-Indigenous commercial, museological and anthropological imposition into Northwest Coast cultural lives, Igharas’s relationship to Northwest Coast art supersedes any false colonial authority over her relations, Northwest Coast artists or art.

The artworks in “womxn and waterways” recognize that water connects us all and, in the face of resource extraction that threatens the wellbeing of all life, that Indigenous women are taking up their roles as caretakers of the water. Carrielynn Victor’s installation A woman’s moon, & remembering sacred connections to waterways (2019) reflects on the knowledge that Stó:lō women carry about moon time and its connections to water—both ancestrally and colonially influenced. With her artwork, Veronica Rose Waechter honours that all life comes from women and water, as told in many Indigenous creation stories. Presented in dialogue with the permanent collection of Bill Reid’s contemporary artworks made in traditional Northwest Coast style, ReMatriate’s project contends with the often male-dominated space of carving and challenges the notions of “traditional” and “gendered” art practices by elevating the often marginalized work of women.

Woman became pregnant with Raven when she swallowed spruce needles from the stream. Through her relationship with water, Woman illuminated the world

Tsēmā Igharas: I met Kali Spitzer, who is in the show, through Jeneen Frei Njootli. I also did a Banff residency with Spitzer and got to know her work, and also worked with her. She makes such a good effort to make relationships with the people that she’s photographing; actually, a huge part of her practice is opening that space. We paired her up with the person who we asked to be our waterkeeper, the person who we honour. Her name is Audrey Siegl and she’s a powerful voice in the community. I wasn’t as familiar with her work but I realized that I’d seen her at so many events when I was looking into her work. We had been talking about who we were going to nominate and went out to a Wet’suwet’en support protest, and there was Audrey. I came back to the next meeting being like, Yup, I’m convinced this is who we need to honour. We had connected Kali and Audrey to make this commission for the exhibition. While this happened, we lost Audrey’s sister and we did our best to try to reach out at that time, as well as give space when she needed that. But we thought that it would be really lovely to honour Audrey’s sister Maria somehow in this exhibit, as a part of Spitzer’s work.

The themes that come out in the exhibition usually happened when I was speaking with the work or listening to the artists speak about the work. When we had the opening, Alison Marks was able to join us. She is a well-known Tlingit carver. She’s also the first known Tlingit woman to raise a totem pole, which is super significant. Mother (2019) is scaled down and intricate, and has been curated in dialogue with Bill Reid’s necklace The Milky Way (1969). Bill Reid’s work responds to a Haida story of Raven bringing light to the world. Marks tells a lesser-known story of woman who gave birth to Raven, who then released the sun, moon and stars into the sky. Woman became pregnant with Raven by swallowing a spruce needle from the stream. Through her relationship with water, Woman illuminated the world. Alison Marks is telling the Tlingit story from the perspective of the mother and from Woman’s perspective.

To be totally honest, The Milky Way is amazing but I don’t think that I really looked at it when I visited the gallery a couple of times scouting for this show and for other events. But I just really appreciated the dialogue between the works by Bill Reid and Alison Marks. The Milky Way was created over several years, too. But I also know a little more about this beading, and that Marks’s work is also labour intensive.

Lindsay Nixon: It’s interesting that The Milky Way is gold and diamond. Is that true?

TI: Did you hear about how Bill Reid’s jewellery got stolen from the UBC Museum of Anthropology? They got it back eventually, but it was a huge scandal. So there’s like mega security in place now. I mean obviously, because he’s using real diamonds and gold.

LN: Imagine getting your practice to the point where you could, like, just buy gold and diamond material to start off with.

TI: Yup, for real. So to have two artists who are directly responding to Bill Reid’s work was something that we prompted in our call for submissions. So half of the work is by artists who we knew were working in this practice on the Northwest coast, who self-identified as Indigenous and women. And we also prompted a call for submissions with a bit of our theme, speaking about water and some of the intricacies of water themes such as connection to ceremony, cycles and connection to being water protectors. The response was overwhelming. I’ve never really been a part of that kind of adjudication before. It was amazing to get that many people who identified within our themes and then submitted to the show. It was very difficult selecting pieces from the work submitted, which was fantastic.

There were two women who met by water and saw how bountiful the land of the Tahltan Nation was. They are the mothers of Tahltan Nation.

TI: Right now, we’re walking through the work by Richelle Bear Hat titled Call me home (2019). Bear Hat’s family, when they talk about where they’re from, they talk about the rivers they care for and the rivers that care for them. Bear Hat comes from two different places—her mother is from the Siksika First Nation, and her father is from the Blueberry River First Nation in Northern British Columbia—and also has this aforementioned kind of connection through water systems across borders. So these are the experiences she’s speaking about in the words included in her work:

Blueberry sipiy

The blueberry sipiy has taken care of my family

When I was a child I was trusted to roam along these sipiy banks

Exploring and swimming with my cousins building relationships

I still carry the confidence gifted to me during that time

The blueberry sipiy gave a glimpse into my father’s childhood

And the landscape that shaped him

Bow Niiyitahtyai

The bow niiyitahtyai has taken care of my family

This niiyitahtyai has shaped my mother’s home and shaped me

Taught me to keep myself safe by respecting its current

Provided space to think and retreat when I feel lost

When the bow breaks through the Niiyitahtyai banks and reshapes the prairies

I am reminded that I am not the only force that shapes my home

Look at what Bear Hat’s work contrasts to in the gallery: a historical archway from the 1920s, preserved as a part of the building, featuring mostly men. All the art in this exhibition is a symbol of strength. And Bear Hat’s subtle, beautiful poetry is making this intervention. We’re really excited about Bear Hat’s work being in this space because it’s ephemeral. We talked about how to have an intervention into this space that’s both quiet and powerful.

There’s another link to ceremony, as well, in the two artworks by Dionne Paul and Lindsay Delaronde. Delaronde is a very powerful speaker and has an articulate of speaking about the connection of women and water, especially in ceremony and speaking from the experience of recently having a baby. Paul also is a mother and depicts taking a hold of your own body, the way that water is cleansing and the way that you could be at one point so free and not ashamed of yourself as a body, as a person and in this place. Paul talks about stories of going to wash with the women in her family. They were washed together in the river and it really wasn’t that big of a deal. Then there is a shroud of the shame that comes with colonialism and taking Paul’s experience away—so Paul’s artwork represents her, taking her family’s water ceremony back.

LN: I like that Paul is bridging the space between them that colonialism caused.

Alison Marks, Mother, 2019. Alder, acrylic paint, glass beads, 24k gold plated beads, druzy crystals. Courtesy the Bill Reid Gallery.

Richelle Bear Hat, Call me home, 2019. Tempera wall painting. Courtesy the Bill Reid Gallery.

Veronica Rose Waechter, Reflections, 2019. Alder, red cedar bark, abalone, acrylic. Courtesy the Bill Reid Gallery.

Lindsay Delaronde and Dionne Paul, We Are Enough, 2017. Photo on canvas. Courtesy the Bill Reid Gallery.

Krystle Coughlin, tu dzen elin (Cloudy Water), 2019. Acrylic, beads, thread, canvas. Courtesy the Bill Reid Gallery.

Carrielynn Victor, Qí:w (Keew) A woman's moon, & remembering sacred connections to waterways, 2019. Tin trunk, acrylic paint, paper collage, deer hide, string, cedar, red dye, glass, spray paint, river stones, jade sphere stones, vintage HBC blanket, spun sheep's wool. Courtesy the Bill Reid Gallery.

TI: There’s no mention of how the Tahltan Nation came about because there’s no mention of men in the story. There are the two mothers of Tahltan Nation. When there was nobody left after a big flood, there were two women who met by water and saw how bountiful the land of the Tahltan Nation was, how many fish there were—and they are the mothers of Tahltan Nation.

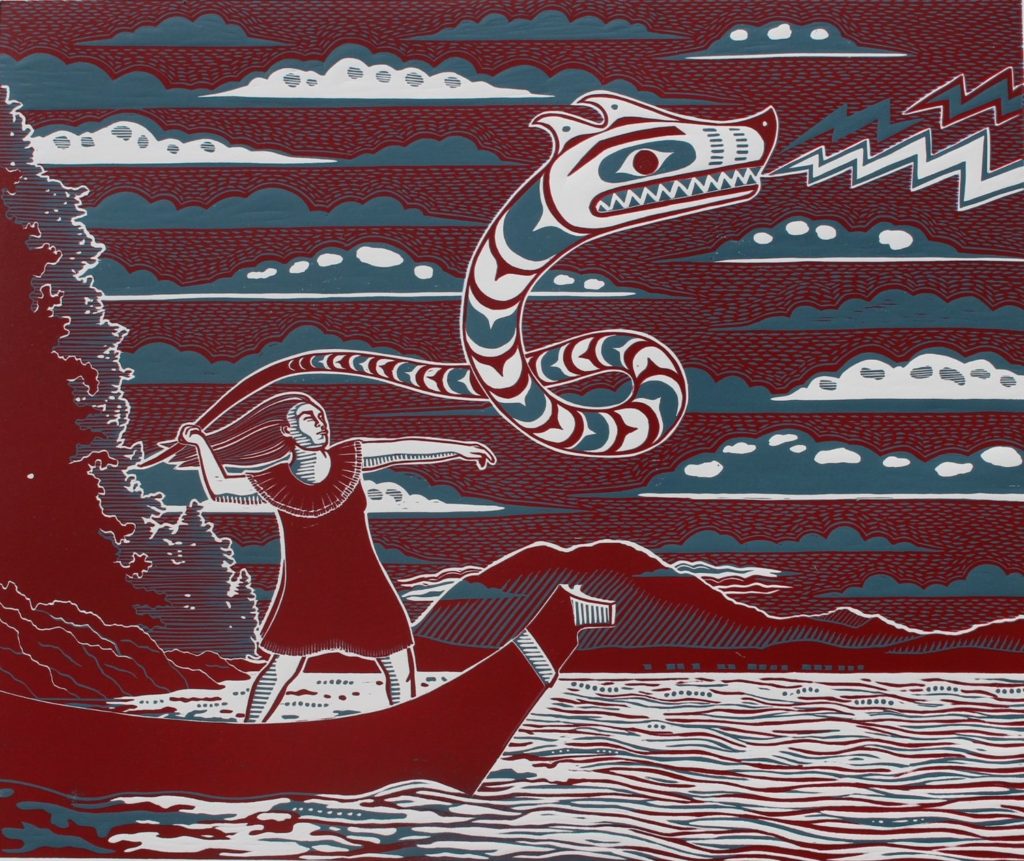

Becoming Worthy (2013) is Marika Echachis Swan’s work. She also comes from a lineage of carvers and her work is also carving. She’s the first person we approached to be in the show. We know that her work is very much in line with the ideals of the show. She’s a printmaker but also, again, carving these layers into her prints: that technique puts her in a carving dialogue. Right now Swan lives in Tofino and does residencies all over the place with master printmakers. She is a master printmaker in my opinion.

LN: ta ts’echo (Big Waves) (2019) by Krystle Coughlin is so interesting. The beading of the water in the work: I like how there are all different colours in it because water reflects so many different colours but people often portray it as just blue. But maybe the colours aren’t a good thing, because it’s cloudy water, so perhaps it’s like polluted water?

TI: I really advocated not to have the artist statements right on the work. It’s very “classic Native art gallery” or even very “public art gallery,” to be like, let’s stand and read the didactic so that we can understand this work. But I reject that because there are so many ways you can enter a work without having to be told what it’s about. And then I also think that it just limits the reading. So it was a conversation we had as curators. Because I come from a Native art background—I went to carving school before I went to Emily Carr—I know the stigmas. I know the way that the West Coast Native artists are represented and definitely want to use that as a platform because I know that it’s really good to get recognized in that field but also kind of launch from there.

LN: When you say “how they’re represented,” do you mean commercially?

TI: Yes.

LN: You have made such a thoughtful curation. I think people—well, I should say a specific commercial audience—would not walk into this gallery expecting to see this kind of work.

TI: The works I think really push the boundaries are actually the artworks integrating text. I think that’s something people would definitely not expect in this gallery. The thing I think about, coming from the Native art background, is that works like this reject the tokenization of Native art—wanting them to be that museum piece to be cherished, preserved and last forever in the Museum of Anthropology, or what have you. But this is actually so much more in line with the way we made our objects to be used, experienced—to have a life and a death.

LN: I also like how you are kind of playing with ideas of the archive, with ReMatriate’s work circulating positive images of Indigenous women of social media too. The photos you circulate exist in some sort of digital archive, and they’ll always exist in that way. The images will probably be destroyed, distributed or whatever afterward, but they still exist somewhere, in a feminist internet archive.

TI: We’re rejecting public domain in our campaigns: permission is not given so that we can then go ahead and do whatever we want with these images once individuals submit them. We have to go and ask contributors individually to make sure that it’s okay if their images are going to be a part of this art show. But it’s the work ReMatriate has set out to do. It’s already a big pillar of what we believe: self-representation, and a protest of misuse of our images and bodies. Art is a good way to speak about those issues.

How often is that talked about in Canadian Art—West Coast art standards? Marks is really an advocate for women carvers and, through studying her language, she’s found that there are these ways you can see the Tlingit worldview, or you can get into a history that’s unknown through this colonial English lens. Where are the records of women carvers, and who talks about that kind of stuff, this kind of segregation, even in our own world? And how is that being influenced and how are these gender politics being worked out? It’s an exciting time to be speaking about these kinds of things in this gallery space.

Marika Echachis Swan, Your Power is Yours, 2019. Limited edition, reduction woodblock print. Courtesy the Bill Reid Gallery.

Marika Echachis Swan, Your Power is Yours, 2019. Limited edition, reduction woodblock print. Courtesy the Bill Reid Gallery.