In Canada, Chinese cultural clusters and spaces are often labelled as “culturally diverse” as part of a multicultural agenda. The frequent comparisons between “the East” and “the West” has us [Canadians of Chinese descent] living with the consequences of these generalizations and the subsequent construction of so-called Chinese culture. So, what does “Chinese” actually mean for people entangled in a Chinese identity? Montreal-based artist Karen Tam and Toronto-based artist Morris Lum both investigate the role Chinese spaces serve in the Chinese community and what they signify more broadly within a culturally Euro-Canadian society.

Tam’s research focuses on the various forms of constructing and imagining cultures and communities through installation work in which she recreates Chinese restaurants, karaoke lounges, opium dens, curio shops and other sites of cultural encounter, while Lum explores the hybrid, and spatialized, nature of the Chinese Canadian community through photography, installation and documentary practice. Lum links the formation of Chinese Canadian identity with the development of geographies that contribute to Chinese Canadian histories, whereas Tam questions the authenticity of “Chineseness” in spaces like Chinatowns where inhabitants are entrusted to perform a certain notion of Chineseness to outsiders. Here, we discuss what “Chinese” and Chinese Canadian experiences mean in relation to their works and in the context of current political dynamics, immigration, gentrification and the cultural shifts happening in Chinese Canadian spaces.

Henry Heng Lu: I am very interested in the relationship between China—as a country, a concept or the culture it points to—and your works. Having that in mind, what does community mean to you? Specifically, what is the “Chinese Canadian community” to you?

Karen Tam: I’ve always been interested in the idea of China and what that can mean in North America and Europe—how some of those ideas and images of China, its community and its culture, are propagated through popular culture and stereotypes, through different interactions. For example: the Silk Road exchanges, the Opium Wars, the literature that came out of that and the travel journals of European explorers. They informed, or misinformed, many populations about another culture and they bring up their own biases and opinions, which can be right or can be wrong. In my work, (particularly the installations where I create interiors of Chinese Canadian restaurants) I am looking at how Chinese restaurateurs play up certain images or stereotypes. So, you find the colour red, lanterns, images of dragons in these spaces…they’ve performed, perhaps, a self-exoticism as a way of economic survival. That also happens in spaces like Chinatown curio shops. Everything within these types of businesses becomes a visual clue in this imaginary “China” for people who are not part of the Chinese community.

Morris Lum: I am thinking about my personal relationship with China. I am from the Caribbean. My grandma was born in Trinidad. My dad was born in Trinidad. My grandpa was born in China and moved to Trinidad. My mother is from Hong Kong. So, there is a push-and-pull relationship with the motherland that signals this idea of displacement, of being removed from the mainland. Growing up in Canada, I kind of fell into that exoticism when exploring the notion of China. It’s seeing it from afar.

The history of Chinese settlers in Canada took shape when a lot of the villagers from China came together to build the Chinatowns, and created smaller communities within them. In most cases, a lot of different villagers pooled their money together and formed associations, so often you’ll see different families in one association. For example, the Gee How Oak Tin Association is a bunch of different families but they came together, in Vancouver, Winnipeg, Calgary. This coming together as one signals the notion of being Chinese Canadian—the idea of being “Chinese” is combined into one identity, versus having more intricate identities from different regions of China. When you move to a different country, you need to survive in a certain way and that was their method of doing so. It’s complex, trying to unpack this question of what Chinese Canadian identity is, and it depends on who is speaking, and on whom you’re speaking to. Are you speaking with someone in the West, from China, from Hong Kong, or from a different generation?

Morris Lum, Calgary Chinese Cultural Centre, Calgary, 2015. Archival pigment print, 101 cm x 1.27 m. Courtesy the artist.

Morris Lum, Golden Happiness Plaza, Calgary, 2015. Archival pigment print, 101 cm x 1.27 m. Courtesy the artist.

Morris Lum, Jinli BBQ, Edmonton, 2015. Archival pigment print, 101 cm x 1.27 m. Courtesy the artist.

Morris Lum, Kwong Wong Kee BBQ Wonton House, 2016. Archival pigment print, 101 cm x 1.27 m. Courtesy the artist.

Morris Lum, Kyu Shon Hong Co Ltd, Toronto, 2017. Archival pigment print, 101 cm x 1.27 m. Courtesy the artist.

Morris Lum, Chinese Freemasons of Toronto, Toronto, 2017. Archival pigment print, 101 cm x 1.27 m. Courtesy the artist.

Morris Lum, Yee Fung Toy Society of Vancouver, Vancouver, 2014. Archival pigment print, 101 cm x 1.27 m. Courtesy the artist.

Morris Lum, Gold Stone Noodle Restaurant, Toronto, 2012. Archival pigment print, 101 cm x 1.27 m. Courtesy the artist.

HHL: Both of your works address diasporic Chinese communities. Morris, could you tell us a bit about the Chinese spaces and structures you’ve been documenting, some of which are being, or on the verge of being, demolished, particularly given the Mainland Chinese influences that seem to be prevailing, for example the bubble tea shops, hotpot restaurants, etc.?

ML: My project “Tong Yan Gaai” (meaning “Chinatown” in Cantonese) comprises images that are visual records of cityscapes in which I highlight historical and contemporary cultural fixtures, such as small mom-and-pop shops, Chinese restaurants and community organizations. I created “Tong Yan Gaai” as a reaction to the immigration wave of the last 30 years, and the disappearance of the original Chinatowns caused by the takeover of suburban Chinatowns, which are centralized by novelty food plazas and shopping malls. Suburban Chinatowns are more affluent and more popular; the downtown Chinatowns are not as busy as they used to be. Throughout Canada, the original Chinatowns are facing similar issues and are now trying to figure out whom they’re catering to: Hong Kong Chinese or Mainland Chinese? The variety of Chinese communities is even more evident in the suburbs. With “Tong Yan Gaai” I am addressing the disappearance of the original Chinatowns by asking: Who is in Chinatown right now? How are they affected by gentrification? And what can be done about the disappearance of Chinatowns?

HHL: There is also an obvious difference in class between the old and new Chinatowns.

ML: Yeah, there is definitely a difference in social class. Most of the immigrants in the more recent wave of immigration, after the 1970s, come from a middle-class background and are able to buy large houses in sprawling suburbs. As a result, [downtown] Chinatown is not the desired destination it used to be. The first wave of Chinese immigrants endured, and overcame, the struggles of racial discrimination and laid the foundation for future generations. “Tong Yan Gaai” also references Cantonese, the early, widely spoken language of the Chinese diaspora, and it mainly focuses on communities from Toisan, Hoiping…

HHL: …the Sze Yap—the four counties of Southern China from which most diasporic Chinese populations originated in the late 19th and early 20th century.

ML: Yes. It’s interesting how nowadays you’re probably not sure which language to speak to the waiters in restaurants in Chinatowns: Mandarin or Cantonese? On a larger scale, what does that mean for the Cantonese language? Is it being removed from the cultural dialogue? When the first generation of [Cantonese-speaking] Chinese Canadians dies off, what will happen to the language?

HHL: How do you navigate through those narratives with your work, Karen?

KT: Well, my work has always been about looking at the older community of Chinese Canadians, like what Morris has just mentioned, and the history of the earlier waves of Chinese immigration to Canada. I’m interested in their experiences because I think it hasn’t really been talked about in the visual arts, or in the history of Chinese Canadian art production. In a way, it’s representing a community that I feel very much part of. One of my exhibitions, “With wings like clouds hung from the sky,” (which will be presented at the Richmond Art Gallery in May 2019) reimagines the studio of Lee Nam, a Chinese immigrant artist who was friends with Emily Carr in the 1930s, in Victoria’s Chinatown. We only know of his existence through Carr’s journals; the installations and works in the show are my gestures to bring out his presence, and they question the absence of artists such as Lee in Canadian and Chinese art histories.

HHL: You recently showed a work in Shenzhen, China, that was completely “made in China.” How was the reception? How did you feel about showing work about the Chinese diaspora in China?

KT: I was invited to be in a group exhibition at the He Xiangning Art Museum in Shenzhen this past fall. It was a survey of Chinese artists living overseas, artists from the Netherlands, UK, USA, Germany, Norway, France, Australia, Malaysia and Canada. I presented an installation called Kiosk for the Silent Traveller (2018); it was the first time I had exhibited in China and I was curious how it would be perceived. It was looking at Chinese spaces and material culture, with references to the Chinese kiosks at World Expositions in the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as the Chinoiserie follies built in Europe and America since the 17th century. As an architectural structure, it’s also about how Europeans interpreted Chinese architecture.

To prepare, I sent the museum a wish list—a plan for building the structure and a list of furniture items with images as examples. I was actually surprised at how the museum had trouble sourcing some of the items. They said the items were not popular in China so they couldn’t find them in the local markets. They even thought about ordering from a US seller and getting them shipped over! It was a work that was almost completely made in China. I did bring one or two items—my fake Chinese antiques. In terms of the reception, it was really positive. There is a curiosity in China for works by Chinese artists from overseas and how they view or represent Chinese culture—or not.

HHL: How do you address and tackle the stereotypical portrayal of people of Chinese descent and the ongoing essentialization of Chinese culture in your practices?

ML: I’m interested in the Chinese Canadian experience versus the exoticism of Chineseness. I try to make connections between being Chinese and being Canadian and how that works together from a Chinese Canadian perspective. When I am photographing Chinatowns I am very particular about the way I am looking at spaces and how my audience will look at them. In some of the interior spaces, there are subtle things, such as a flag of China, Taiwan or Canada. I sometimes ask people to keep things unkempt, so that you see, for example, Tim Hortons cups left on the table. I keep that in the shot to help contextualize how the place [is being used], how it should be seen and identified, without being exoticized.

KT: I use a lot of humour in my work to talk about stereotypes, racism and representation because I find that with humour everyone has the ability to laugh at themselves. It opens up conversations. When I’m viewing artworks, I find that if I feel I’m being attacked, I’m already on the defensive and probably not going to engage in the work. I try to make my work seductive enough that it draws people in. That’s one way to start engaging people about the essentialization of Chinese culture or their own biases—and my own as well.

HHL: Let’s look a bit more closely at an issue that has put increasing pressure on Chinese spaces these days. I wonder how you, as artists, situate the issues of gentrification affecting Chinese Canadians? Further, how do you take on the urgency of addressing the rapid spatial changes in the community?

ML: My work speaks to the notion of loss and of losing your own history. I try to record spaces and places before they disappear. Factors like gentrification play a role in the loss of Chinese spaces. My method raises the question: How do I, as a Chinese Canadian, deal with gentrification in the neighbourhoods I’ve known for a long time? As an artist, my reaction is to record and to try to keep the stories alive through photographs in order to solidify their importance in history.

KT: By recreating Chinese spaces and collecting Chinese objects, in a way it’s related to what Morris just described—I also document what is disappearing. Gentrification is going to happen, no matter what but I am concerned about the changes in Chinese spaces. I guess I can only speak about Montreal’s Chinatown since I am most familiar with it. For example, the Chinese Cultural Centre: it took the longest time, decades, to get it off the ground, to open, and now—not to get into the whole messy story behind it—it’s closed. I heard that the building had been acquired by a French businessman to open a music school. He had no idea about the history behind this building and he probably wasn’t at all aware that it’s in Chinatown. [In Montreal] we are losing more Chinese spaces, which are already confined due to city by-laws and annexation by governments at all levels. Chinatown cannot expand to the north, south, west or east.

HHL: I like how building archives is one of your ways to respond to gentrification, and further, to preserve memories.

ML: Yeah, speaking to Karen’s restaurant installations, they are records of the small-town Chinese restaurants that are slowly dwindling and becoming somewhat extinct because they represent the specialized taste of North Americans. But the palate of North Americans has expanded and more specialized Chinese cuisines, for example Northern-style or Sichuan, are now more accessible and accepted in small towns. Chinese restaurants first popped up in small towns after the gold rush in the Fraser Valley and, after the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway, the first Chinese settlers opened restaurants and expanded outside of BC to Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario…Karen’s work has been recording that history.

Karen Tam, Jardin Chow Chow Garden: A Division of Gold Mountain Restaurant, 2007. Installation with video, various décor, furniture, objects, fabricated, collected, and rented from prop warehouses, local community and businesses to recreate a chop suey house of the 1960s. As installed at Expression, Centre d'exposition de Saint-Hyacinthe's ORANGE event (Saint-Hyacinthe, Canada)

15 x 8.5 x 4.3 m. Courtesy the artist.

Karen Tam, Jardin Chow Chow Garden: A Division of Gold Mountain Restaurant, 2007. Installation with video, various décor, furniture, objects, fabricated, collected, and rented from prop warehouses, local community and businesses to recreate a chop suey house of the 1960s. As installed at Expression, Centre d'exposition de Saint-Hyacinthe's ORANGE event (Saint-Hyacinthe, Canada)

15 x 8.5 x 4.3 m. Courtesy the artist.

HHL: Moving forward, how do we take up (more) spaces as artistic and cultural practitioners?

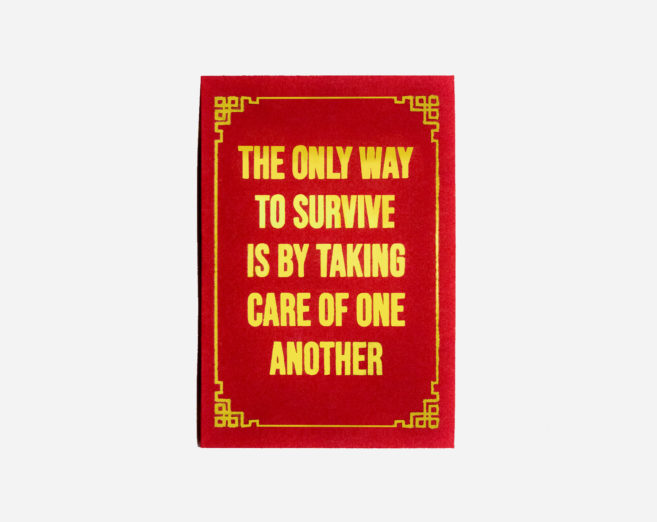

KT: One important thing is to support one another, as well as to share and to create your own opportunities. Like, for example, what you and Winnie Wu are doing through your curatorial collective Call Again: sharing works of other Chinese Canadian artists. One of the other concrete ways is to join boards, to be on juries, to be in leadership roles, etc.—to join and be part of the decision-making processes. Being in those types of positions is important and will make a difference.

ML: It’s also about spreading the word, to get the history out there. The canonization of art history and Canadian history needs to be disrupted; [we need to be] acknowledging that there are other histories. We need to be out there. In doing that, we also need to speak to the next generation and newer Chinese immigrants. They shouldn’t take what their predecessors have built for granted. They need to know the history and then learn how to keep things going.

Morris Lum, Wong Kung Har Wun Jun Association, Toronto, 2016. Archival pigment print, 101 cm x 1.27 m. Courtesy the artist.

Morris Lum, Wong Kung Har Wun Jun Association, Toronto, 2016. Archival pigment print, 101 cm x 1.27 m. Courtesy the artist.