There is something otherworldly to Ursula Johnson’s baskets. Her woven forms creep arachnoidally, split in half, protrude, confine and intertwine, all the while maintaining the distinctive decorative curl, pattern and underlying structure of Mi’kmaw basketry.

Johnson’s practice often occupies itself with transformation—a process which follows the harvesting of a tree, through its processing into splints and the final completion of a basket. Formally, too, her baskets and performances turn toward the transformation of the self. In a set of works which began while she was an undergraduate at NSCAD, Johnson cocoons herself inside a basket, a process which has since recurred in her work, alone and with other performers. But for Johnson, transformation also describes the shifting cultural significance of the basket form—from traditional craft, to collector’s commodity, to museum artifact, to archival remnant. A skilled researcher as well as a multi-disciplinary artist, she seamlessly interweaves narratives of colonization, tourism, language, memory and ancestry.

On June 6, Saint Mary’s University Art Gallery in Halifax opens Johnson’s latest exhibition, “Mi’kwite’tmn,” and on June 20, she will enact a performance as part of “Making Otherwise” at the Carleton University Art Gallery in Ottawa. In this advance phone chat, Johnson—who was also longlisted for this year’s Sobey Art Award—discusses museum authority, the competing languages of basketry, and the dynamics of performing craft.

Alison Cooley: I’m wondering if you could begin by describing your upcoming exhibition at SMU.

Ursula Johnson: The whole exhibition is titled “Mi’kwite’tmn,” which is a Mi’kmaw term which can be used in two different ways. It can be used as a question—“Do you remember?”—or it can be a statement saying “You do remember.” And the exhibition is about memory around language and history and artifacts.

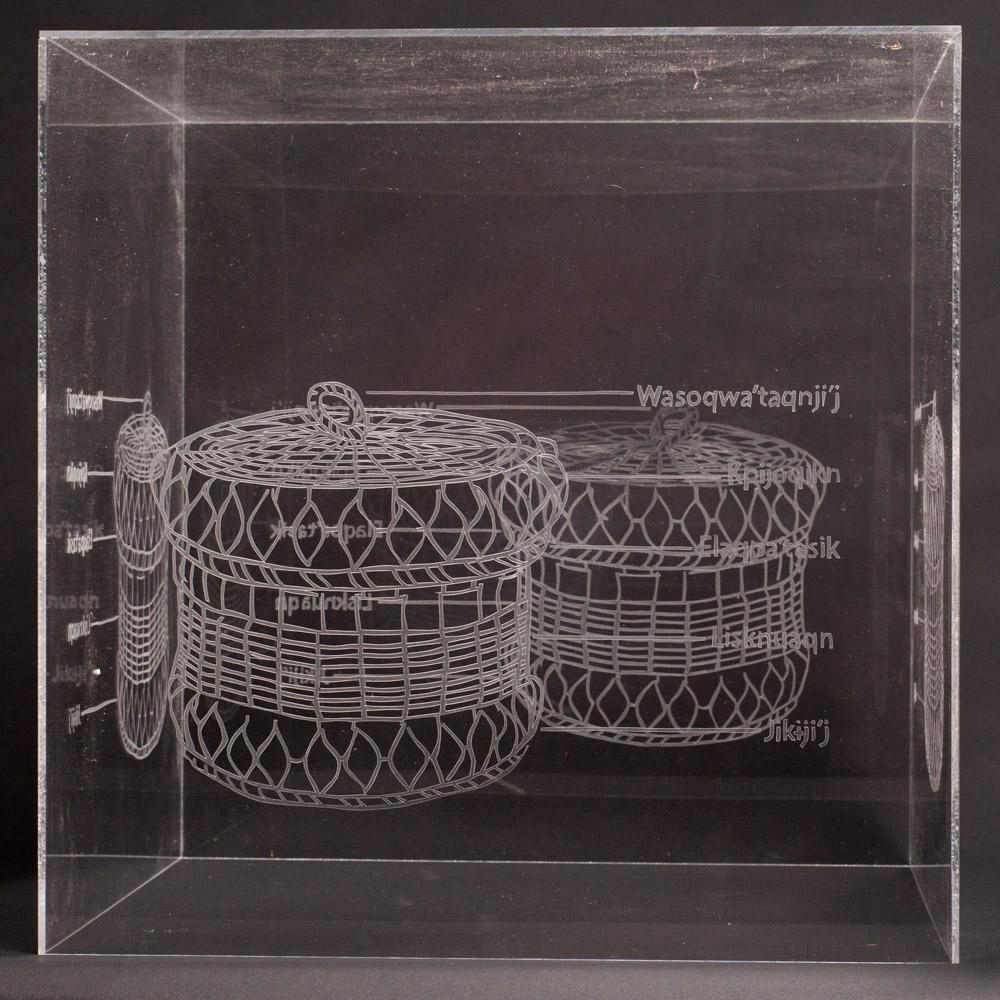

The main space in the exhibition consists of a dozen museum-type vitrines, which are Plexiglas cases. Usually when you walk into a museum setting, you anticipate that you’ll see an artifact under this case, which has been protected and preserved in some way, because it’s something that is historically significant, usually within an anthropological or ethno-cultural context. For these vitrines, as you approach them, you realize that there is nothing in the case, and that they’re actually empty. But the vitrines are the work itself: there are sandblasted images that have been cut into the Plexiglas, and then there’s a long, arduous process that leads to creating the image on the plastic. The images are all simplified images of my great-grandmother’s baskets, which have been dissected in that Western, diagrammatic sense where there are parts that tell you what each component is.

This work came out of an initial conversation with my great-grandmother where we talked about the different parts of the basket, when I was learning from her. She was talking about how each of the terms that describes each part of the basket is very specific to the way that that material has been manipulated. She said that when the art dies, the language will die with it, because that language is not used for anything else except manipulating the materials to create the object. Essentially, these cases are housing the language that’s in there, quite literally, but also symbolically, because the case is empty and the language is dying along with the traditional art form of Mi’kmaw basketry.

AC: A large part of the SMU exhibition is themed around memory, and also the kind of authority that language provides—and alongside English and Mi’kmaw, there is also the language of museological display. How does that play out throughout the rest of the exhibition?

UJ: I wanted to speak about how indigenous cultural objects come to the museum. Often they have been confiscated, or maybe even illegally purchased or bought, or handed down from someone’s collection who may have historically purchased an item in a trade commodity context in the 1800s or something. Every time you walk into a museum, you expect to see objects that have some sort of historical or cultural value. They’re no longer considered living objects, because they have been archived in this space.

Off the main space at SMU, there will be an “archive room” that houses 21st-century basket forms which I had created initially in 2010. They’re all non-functional forms, but they give reference to functional forms. I’m trying to play a little bit on the idea of speculation in regards to how these objects come into the museum: they’re studied, catalogued, categorized, and then kind of put away into wherever it’s speculated that they belong.

There’s an interactive component, as well. In the archive room, there will be shelves all around the perimeter with these 21st-century baskets. There’s going to be a station with a computer terminals and a barcode scanner, so you can go into the space and put on white gloves as you would in a museum archive to get the object off the shelf, put it at the station, and scan the barcode that’s on the tag. That retrieves the information about the materials, the date that it’s speculated to have been created, what its intended function would have been, its dimensions—all of the information that you would expect to find in an archive, except that because these objects are new, there’s really no historical context in which they exist.

There’s a really small basket that’s in the style of a traditional hamper basket that you would see at somebody’s home for their clothes, and the description may say that historically, these types of baskets were created for the small people in the community, whose clothes weren’t that big, and that somebody with small, nimble hands would have created only these types of baskets, because nobody else could make them. But it’s all farce.

There’s going to be another media component where there are surveillance cameras that are in the space that follow the viewer as they enter the space. I’ve been interested in a number of different ideas around indigeneity and surveillance, and how I could best help the viewer to understand that feeling of being surveyed.

AC: What is it about the feeling surveillance that you’re hoping to provoke?

UJ: If non-indigenous viewers come into the space, I need to create a way of feeling that they’re being watched. Because it’s very different when your cultural context comes into play…. For many of us who exist within marginalized groups in society, if someone is standing in the corner of the room, then you’re being watched. But somebody else might be thinking, “Oh, this person [in the corner] is here to help me! They’re not here to keep an eye on me and make sure I don’t do anything wrong.” So I wanted to create that feeling of being watched and not being trusted by using digital media by having these surveillance cameras in the space.

The third component of the exhibition is going to be a performative space where I have a number of family artifacts that have been handed down to me that are used specifically to process a log to create materials for basket weaving. In 2008, a couple of years after I graduated, I received a research grant from Canada Council to research netukulimk—a Mi’kmaw term that loosely translates into “self-sustainability.” I wanted to research how self-sustainability applies to the history of Mi’kmaw basketry.

One of the things that I learned from that research is netukulimk is really about the land around you, and having a mutually beneficial and respectful relationship. One of the interviews that I did for the project was with my great-grandmother, where she had said, “Well, I don’t think there’s any hope for Mi’kmaw basketry, because these kids don’t know anything about the forest. They can’t go into the forest and tell you the difference between a red maple and a striped maple, let alone how to harvest it, or when to harvest it and when to process it.”

I realized during that conversation that I was one of these kids who didn’t know. So I took it upon myself to go to the elders in the communities and to learn how to properly re-acquaint myself with the land, and the materials that I was going to be engaging with, because I felt it would be very disrespectful for me to just start using these materials that have been used by my family and my community for such a long period of time and to not know what I’m doing.

During the performance [at SMU], I’m actually going to be sacrificing a tree. I’m going to get the log and process it in the space, but I’m only going to do the first four steps of processing, instead of the whole twelve steps. I want to create this really dynamic, hasty energy in the space, where I look like I’m fumbling over my tools and I don’t know what I’m doing, like I’m essentially just killing this tree instead of actually creating something out of it that could be later used as materials.

I’m essentially going to obliterate the tree in the [performative] space. And that’s to talk about this disconnect between people from my generation in regards to our relationship to the natural world.

AC: I saw a bit of documentation of a work called L’nuwelti’k—a performance where you covered peoples’ faces with basketry. This metaphor of cocooning occurs again and again in your work. Is there an element of that in this exhibition?

UJ: The whole idea of the cocoon in my previous works has to do with this idea of metamorphosis that comes out of protecting something, or describing some type of change that’s going to happen.

With the museum vitrines, it’s all about trying to protect the language, or the history, of this traditional aboriginal art form, and the language associated with it. But it’s also about that fear that nothing is going to come out of it. You know, like my great-grandmother said, that “there’s no hope for the art form to exist.”

But I strongly do believe that there is hope for the art form to exist. The only thing that I can perceive is that it’s going to change. Because when we have any type of art form—like if you look at traditional craft like carpentry or weaving, tapestries or anything like that—they always change as time progresses. There’s always going to be a way for it to manifest itself in a different context. I think that those cases preserve that memory—but then, in the adjacent room, that memory is brought back to life, but in a different context, so it’s shifted into something else.

AC: I think basket-weaving is often thought of as a sort of domestic, feminized sort of craft, but in fact there’s a huge component of physical labour in it, in order to acquire the materials. So it strikes me that that’s an important way to draw attention to the fact that the practice is so bodily and involved, as well. How are you thinking about performing that labour?

UJ: It’s funny, because I was talking to Robin Metcalfe, the curator at SMU, recently. I want to start the performance well in advance of the opening, so that by the time the doors open, I’m already drenched in sweat and exhausted. And then I’ll continue for the next hour, and then can mingle for the next 45 minutes.

I’m a bit of a performance junkie. I want to already be in that physical, visceral zone that I enjoy being in: in performance. But I also want people to see that it’s not that the doors open and then I go over and start doing something—I will have already been in progress.

AC: Your family and your ancestry are to be quite present in this exhibition. How do you negotiate the relationship between these fictitious baskets and the baskets that are real items that were produced by your own family members or your own ancestors?

UJ: There’s always a struggle that happens in my mind in regards to the authentic versus the inauthentic. That’s also because I’m a bit of a research junkie, so whenever I research something, especially within my own practice, I always look at the question, “What is the definition of authenticity, and who determines if something is authentic or not?”

That’s something that I like to play with in my practice. I have a performance that I’ve done quite a number of times called The Indian Truckhouse of High Art, where I take on the character of this street pedlar who has all these objects—but they’re all mass-produced, appropriated objects that I found in dollar stores that are considered to be “Indian-looking,” or stereotypically kind of Indian. I have a hand-dyed piece of yarn that’s attached to each object, with a tag that says “This object is 100% authentic Indian high art,” and on the backside is a price tag. But the object that the tags are actually referring to is the hand-dyed yarn, not the object that I’ve bought from the dollar store. The prices on the back of them all range from $17.20 to $17.90, which reflect the consecutive dates of treaties between the Mi’kmaw and the crown, from 1720 to 1790.

This character sits on the street, and all of these people come by, and she doesn’t speak very much English—she can say, like, “money,” “sale,” Halifax,” “buy,” but then the rest of it is in Mi’kmaw, and it kind of plays on this idea of the exoticized tourism object. It’s really funny when I do it on the streets of Halifax in the summertime, and it’s like, “Oh,wow! Look at this beautiful dreamcatcher! Oh, this one here has a wolf on it!” And everyone’s so excited—but it’s all come from the dollar store, and nobody cares about the tag, or the interaction. They don’t think about what is being presented to them as an authentic artifact, or a tourism commodity, or whatever. I like playing with those ideas of authenticity or inauthenticity.

In regards to my family, they get a big kick out of that trickster mentality, like, “Are you really going to make a basket around yourself and be inside?” And I’m like, “Yes!”

I come home and my grandmother’s like, “Did you do that thing again?” I say, “What thing?” She says, “Where you were inside the basket?” And I say, “I’ve done it three times so far!” And she says, “Are you going to do it again? ‘Cause I want to see you next time. I think it’s so crazy and so funny, but I’d love to see it!”

So my family gets a kick out of this strange sense of humour that I have in regards to the materials, and some of them get the idea that I’m playing with notions of authenticity in regards to indigeneity and that I’m critiquing the institutions that are presenting this notion of authenticity. Other people may not necessarily get it, but they think that it’s funny anyway.

Ursula Johnson’s exhibition at the Saint Mary’s University Art Gallery in Halifax opens at 6 p.m. on June 6, and runs until August 3. Her performance for the Carleton University Art Gallery in Ottawa will take place June 20 on campus between 11 a.m. and 3 p.m., and she will give an artist talk that evening at 6 p.m. at CUAG, with her work being exhibited there as part of a group show until September 14.

This interview has been edited and condensed.