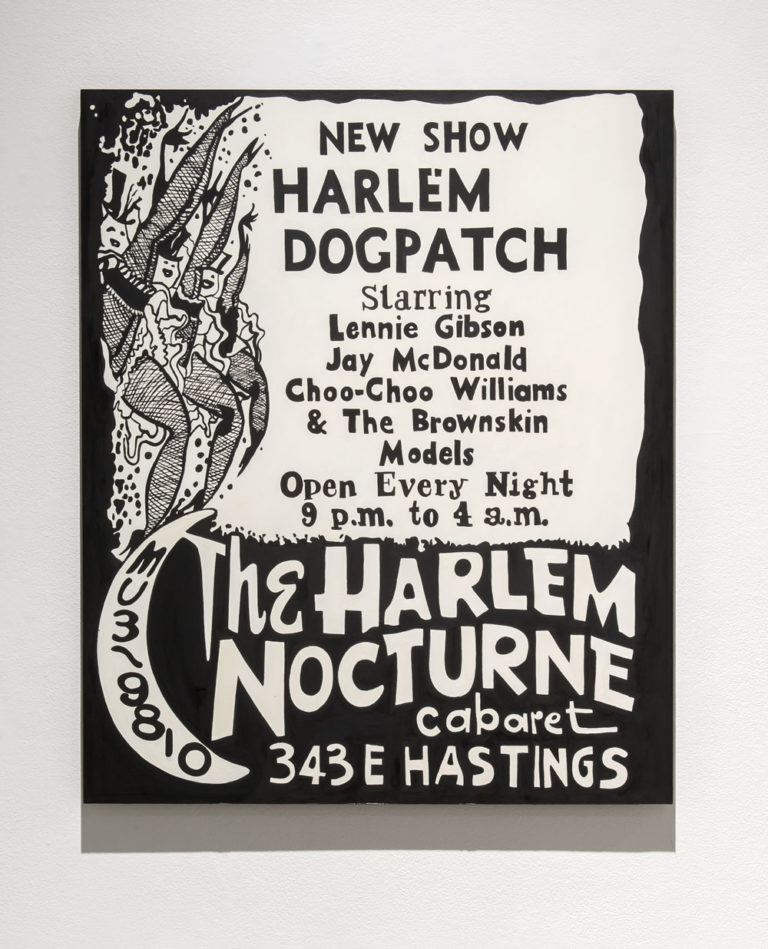

Artifacts of Black Vancouver define much of “A Harlem Nocturne,” Deanna Bowen’s new exhibition at the Contemporary Art Gallery (CAG). A black-and-white poster for “Harlem Dogpatch,” a cabaret show at the Harlem Nocturne, a Black-owned Vancouver bar, hangs on a gallery wall near a projection of a 1978 report on racism against Black Vancouver residents. A once-classified document, framed and time-stamped, details the 1948 Vancouver travels of Katherine Dunham, the leading 20th-century African-American choreographer. Projected on a white wall is black-and-white film footage of Black dancers performing on Vancouver’s 20th-century stages. These artifacts and archives might surprise some, because, as artist Deanna Bowen told me, “the city insisted” there were “no Black people.” In this exhibition, which includes new and older works, Bowen confronts that false narrative.

“We’ve been here a long time and we are still here.”

The confrontation is also deeply personal. Bowen is a Black Canadian artist whose autoethnographic work engages her family history, Canadian history, technology and authorship. In Wake Video, a sheer black veil covers an image of women in Bowen’s family, many of whom worked at the Harlem Nocturne, the bar that inspires the show’s name. Upon closer inspection, this image moves; it is a recorded video of the family portrait. A set of earphones invites viewers to watch the moving image and listen to an interview between Bowen and her mother, in which they talk about life and work in Vancouver.

I spoke with Deanna Bowen about the aesthetics and archives of “A Harlem Nocturne,” her family’s connection to Vancouver’s entertainment sector and what her work means for documenting the absented presence of Black people in Vancouver and Canada.

Jasmine Mahmoud: Tell me about the title. The word “nocturne” brings to mind a composition, or a nighttime scene. It is also in the title of the 1939 song “Harlem Nocturne,” written by Earle Hagen and Dick Rogers, which became a famous jazz standard. What were you aiming to address by calling this show “A Harlem Nocturne”?

Deanna Bowen: It’s a reference to the bar. The Harlem Nocturne was a Black-owned, family-run nightclub in the city. The owner, Ernie King, was married to my grandmother’s niece, who was a “shake dancer” at the club. My mom worked there, my grandmother worked there, my grandfather drank there, Leonard (Lennie) Gibson performed there [and] I suspect my great-uncle Herman Risby did too. It’s a central part of the family narrative.

Deanna Bowen, Harlem Dogpatch,

2019, installation view from “A Harlem

Nocturne,” Contemporary Art Gallery,

Vancouver, April 5–June 16, 2019.

Photo: SITE Photography

Deanna Bowen, Harlem Dogpatch,

2019, installation view from “A Harlem

Nocturne,” Contemporary Art Gallery,

Vancouver, April 5–June 16, 2019.

Photo: SITE Photography

But then you mentioned this other interpretation of nocturne, this nighttime scene or this idea of the night. This community, this collection of family members, are all entertainers, and all would’ve been integral players within Vancouver’s nightlife. So I wanted to bring that forward. It’s a nod to this entertainment community, but it’s also something that I needed to mark, this network of Black bodies that were most visible in the darkness of night. Because, over many decades, there is so much connected to these bodies in the nightlife of the city, and it helps me understand that community.

One of the sadder things about the city I’ve encountered is that there aren’t many descendants memorializing Hogan’s Alley, a central neighborhood community that was in the Main and Hastings area. What becomes the consistent narrative is that there are no Black people in the city. I hope that the show presents enough material to [challenge] the insistence that we aren’t here. It’s a shame that we continue to tell ourselves that and to perpetuate this sad, insidious indoctrination, because the community is right in front of us. [Somehow] we’ve come to digest and believe the lie that we’re not here. I hope the show gives enough concrete evidence to speak to a long-lasting presence.

JM: “A Harlem Nocturne” mines repertoires of your family’s histories through a variety of sources: interviews you conducted, music scores, archival maps, videos and images. How are you thinking about the repertoires of these histories as they dialogue with the sensorial orientation of the archives in the gallery space?

DB: The process of creating the show is about witnessing Black bodies, and also witnessing other people witness Black bodies—there’s something important about bringing all those things to the forefront. The few archives I could find around blackness in this country, in this city, are largely created by white organizations, [and] are more often than not quite scant and poorly organized. So some of this work is an effort to salvage an archive and bring forward what is known.

But then if we’re talking about Vancouver, it’s so important to bring all this material forward, because it’s a city that actively insists there is no Black community, that it was eradicated in the 1950s and early 1960s with the creation of the Georgia Viaduct. Bringing all this material forward is a testament to the fact that there’s a history that long precedes that moment in Vancouver history. We’ve been here a long time, and we are still here.

“Halifax, Africville, North Buxton, Dresden and all of these other Black places across the nation are read as exceptional defunct communities, but they are actually all part of a bigger discussion about Black migration and historical erasure.”

JM: From the artifact with Katherine Dunham’s name, to the video of choreography, to the score, to the maps, to—very differently—the video ON TRIAL The Long Doorway, this exhibition traces the past presence of Black entertainment workers, especially those in Vancouver. How were you thinking about what those archives look like and mean for those entertainers?

DB: [I consider] the way that Vancouver speaks to this absence of blackness, this very present absence of blackness. I’m thinking about how rich these communities of entertainers were. It wasn’t only entertainers. These communities were quite strong: they created spaces for themselves and the Harlem Nocturne—a Black-owned bar—was an example of that.

But also, [I considered] the tendency for Black and Asian entertainers to perform together in Hogan’s Alley, also known as Black Strathcona or, at one time, Nigger Heaven. There was this really rich, flowing engagement between Black and Asian performers that is a part of the broader foundation of the history that surrounds the viaduct. For example, Lennie Gibson and Denise Quan danced together in numerous CBC productions in the 1950s. As far as aesthetics go, their pairing on broadcast television sparks other conversations about permissible interracial pairings.

Deanna Bowen, Katherine Dunham in Tropical Revue, 2019. Installation view from “A Harlem Nocturne,” Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, April 5–June 16, 2019. Photo: SITE Photography

Deanna Bowen, Katherine Dunham in Tropical Revue, 2019. Installation view from “A Harlem Nocturne,” Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, April 5–June 16, 2019. Photo: SITE Photography

The Dunham piece [Katherine Dunham in Tropical Revue] is important for a whole bunch of reasons. She is the person who picked up Lennie Gibson, a family member [of mine], as a dancer for a show in Vancouver, and who trained him in the Dunham Technique. So I’m also looking at that: Dunham’s travels through here, and the awareness that there was very forward-thinking contemporary dance flowing through the city as early as 1942. The artifact I recreate for Dunham is a God-awful, kewpie doll–like statuette of Katherine Dunham, a contest entry created in 1947 by a hobby artist at the Pacific National Exhibition. The sculpture this person created carries all the stereotypes that we know of Black Sambo, or Black mammy caricatures of that particular era of representations of blackness.

There’s a black-and-white photograph of the statuette tucked into the city’s archive, and I thought it was super important to remake it—to enlarge it and bring it back into the space, manifest it as it would’ve looked in the time it was made. Because again, the city insisted that aside from no Black people, it also had no racism. It’s important to bring forward these artifacts that very pointedly speak to ignorance and a lack of tolerance in the city. Dunham was also a civil rights activist, and I thought it was important to highlight the presence of Black resistance that flowed through the local Black community.

JM: I appreciated how the four screens showing ON TRIAL The Long Doorway turned on and off in a way that directed my viewership and awareness of what I could and could not see. What was your intent with using the four screens to animate the video and the script?

DB: Some of it’s a reference to the original live performance. The footage comes from a show the CAG had supported at Mercer Union in Toronto, also called “ON TRIAL The Long Doorway.” The show was based on a CBC Toronto live-to-broadcast teledrama, and we had a three-camera setup that recorded it all over a series of weekends. Audience members and gallery-goers were allowed to come and watch, but only if they sat within the set. We didn’t give them seats to passively watch—the notion was that these audience members were implicated in the performance of the re-staging. A lot of that is coming out of an understanding that Mercer Union, like the CAG and many other Canadian galleries, has a predominately white audience. I didn’t want to create work that made for a passive viewing experience for a white audience, who would go away and say, “Wow. I’ve been educated.” I definitely didn’t want to do that. And because we re-staged the footage at the CAG without the set, I wanted to at least maintain some of that wide-focus viewership, where a predominately white audience is witnessed as they view a conversation or a performance that speaks to blackness. This circle is set up so that as an audience, you’re obliged to walk into the centre of the four inward-facing monitors, and in doing so, anybody else who comes into the space watches you watch it as well.

I was also thinking about the original three-camera shoot and how that provides three different perspectives on every aspect of the performance. I cut the raw footage into four channels and gave it a visual rhythm. It’s a three-hour-long piece, so I knew I needed to figure out a way to keep people in the work. It’s already difficult, race-based material, so I needed to give some visual cues—which is something I do a lot. Given my mostly white audience, I know that there has to be some sort of device or cultural connection to keep them in the story, keep them hooked. Sometimes it’s about giving the viewer some space, some breathing room to negotiate the story. That’s where the roving black channel of the piece comes in as a space of visual and narrative rest. A place outside of the story. So yeah, I’m thinking very much about the different perspectives, and then how that flows into a discussion about different ways of understanding blackness, Black Canadian identity and all of the related things that come into that equation.

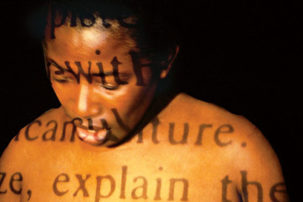

Deanna Bowen, installation view from “A Harlem Nocturne,” Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, April 5–June 16, 2019. Photo: SITE Photography

Deanna Bowen, Gibson Notations 1, 2 and 3, 2019. Installation view from “A Harlem Nocturne,” Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, April 5–June 16, 2019. Photo: SITE Photography

Deanna Bowen, ‘Theatre Under the Stars’ cast photo from Finian’s Rainbow, Circa 1953, 2019. Installation view from “A Harlem Nocturne,” Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, April 5–June 16, 2019. Photo: SITE Photography

Deanna Bowen, The Promised Land, 2019. Installation view from “A Harlem Nocturne,” Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, April 5–June 16, 2019. Photo: SITE Photography

JM: The show arranges archives from Canada and the United States, archives of Black people who have been moved by racism, and who have nevertheless shown resilience. What does this show mean, geographically and racially, for Vancouver, Canada, the United States and North America?

DB: As it relates to Vancouver, it’s important to have established that there is a Black history that has long been here. My family actually migrated from the [US] South through Vancouver in the 1910s. We’re talking more than 100 years of Black presence. So there’s that. But, there’s also this part about Vancouver being a stopping point for the Risby family—at least on my grandfather’s side of the family. This is the mapping of a migration from Kentucky to Yellowknife: a migration from Kentucky to Kansas, Kansas to British Columbia, and then ultimately to Yellowknife—and all of it spurred by white supremacist violence.

In an American context, this community of Black people answers a lot of questions about what happens to the descendants of all-Black towns in Oklahoma and Kansas. My grandfather’s side comes from Nicodemus, which still exists, and my grandmother’s is from Clearview, in Oklahoma. This is an extension of that American historical query about what happens next. Because this is the answer. We came here.

Within a Canadian narrative, all of my work has been about tracing my way back home. I left here in ’94. I ran from here. It was just too much to handle this family history. So I went to Toronto, and all of my work has been a means to backtrack and understand this community. And so in many ways, by doing that over 20 years, I’m doing the work of mapping out blackness across the country.

Again, we have been here for a long time. My family’s narrative is speaking to more than 100 years of Black presence that has everything to do with a migration to and from the United States and Canada. It’s a step in the direction to making connections between Halifax and Africville, [North] Buxton, Dresden and all of these other Black places across the nation that are read as exceptional defunct communities, but could all actually be part of a bigger discussion about Black migration and historical erasure. Because I’ve gotten so much insight with the community, as old as it is, I feel I have a responsibility to do the work. This work is about writing history through artmaking.

JM: Do you have any other closing thoughts?

DB: Oh. I just hope I’ve left enough clues for the next generation of researchers. I hope I’ve placed and re-placed this Black community, given it some glory and put it back on the map.

Deanna Bowen, Rupert Lanes (after Wall), 2019. Installation view from “A Harlem Nocturne,“ Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, April 5–June 16, 2019. Photo: SITE Photography

Deanna Bowen, Rupert Lanes (after Wall), 2019. Installation view from “A Harlem Nocturne,“ Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, April 5–June 16, 2019. Photo: SITE Photography