Last year, when Thelma Pepper turned 100, she learned Saskatoon’s Remai Modern would feature her work in a major retrospective.

The Remai announcement about the show promised to highlight Pepper’s depictions of elderly women, women in small town and rural life, and a selection of audio interviews she recorded. The announcement also promised additional images by Rosalie Favell, Mattie Gunterman, Dorothea Lange, Frances Robson and Sandra Semchuck—works that offer what the museum called “intimate and critical insights” into Pepper’s work.

This big museum show has been a long time coming—but so had Pepper’s practice overall.

Pepper, like some other women artists of her generation, only began her own photographic practice after her four children were grown—for her, when she was 60 years of age.

Likewise, Pepper’s first solo show, “A Visual Heritage, Images of the Past, 1900–1930,” took place in 1983, in her early sixties. It was followed by the national touring show “Decades of Voices,” which launched in 1990 when she was 70, and that looked at residents of a seniors’ home a block away from her own house on Temperance Street in Saskatoon. For these shows and others, she spent hours printing the photos in her small family darkroom at home.

After that, Pepper published four photo books, with a particular interest in portraiture and older women’s lives in the province. In 2014, she received the Saskatchewan Arts Board Lifetime Achievement Award, and in 2018 she received the Saskatchewan Order of Merit.

Sadly, Pepper was not able to see the achievement of her Remai Modern show “Thelma Pepper: Ordinary Women. A Retrospective” when it opened last week on February 13.

She died on December 1, 2020, at the age of 100.

But in October 2020, just a few months before she passed, Pepper got on the phone with artist and writer Sarah Sarofim. Part of their conversation made it into the Preview section of our Winter 2021 print issue, Tangents. In this expanded version of the interview, approved by Pepper’s estate, the artist speaks about her earliest memories of photography, as well as the power of storytelling and voice.

Thelma Pepper, Evangeline’s Mother, 1993. Gelatin silver print, 38.5 x 38.5 cm. The Mendel Art Gallery Collection at Remai Modern. Gift of the artist, 2001.

Thelma Pepper, Evangeline’s Mother, 1993. Gelatin silver print, 38.5 x 38.5 cm. The Mendel Art Gallery Collection at Remai Modern. Gift of the artist, 2001.

Sarah Sarofim: What first drew you to photography? Were you always interested in documentary approaches to that work?

Thelma Pepper: I’m always interested in documentation. I am generally interested in history, especially the history of Saskatchewan and the West. I originally came from the Annapolis Valley in Nova Scotia.

SS: When did you move to Saskatoon from Nova Scotia?

TP: 1947. I just had my 100th birthday in July, so I’ve been here a long time.

SS: Happy belated birthday!

TP: Thank you. We had baked beans, Nova Scotia baked beans and bread. That was our menu.

SS: That sounds delicious.

TP: It was.

SS: So did your interest in photography and documentation start back in Nova Scotia?

TP: Well, my father and grandfather [in Nova Scotia] were both amateur photographers—but they were serious ones. They had a lumbering business and my grandfather was one of these people that had to have “the first” car and “the first” camera.

Among my first memories of my dad was him warning us all that he was going to be printing photographs, so anybody that wanted to use the bathroom must do it immediately—because the bathtub was the darkroom.

Later, I spent hundreds of hours in the darkroom with my dad as a teenager. And as I grew older I inherited many of his old negatives.

One more thing about my dad: He wasn’t accepted in the First World War because of his nervousness. But when he had a camera in his hand, he was a different person—he found his passion at an early age.

Also, during the Second World War, there was a huge air base established just a mile from my hometown. And my dad liked nothing better than photographing some of the airmen and sending the photos to their homes. He’d send photos to their moms and dads all over the Commonwealth, really. They were only 16, 17, 18, and to get a photograph—that was exciting for them.

Thelma Pepper, Aline of Tway, 1993. Gelatin silver print, 38.1 x 38.4 cm. The Mendel Art Gallery Collection at Remai Modern. Gift of the artist, 2001.

Thelma Pepper, Aline of Tway, 1993. Gelatin silver print, 38.1 x 38.4 cm. The Mendel Art Gallery Collection at Remai Modern. Gift of the artist, 2001.

SS: It seems as though, through your dad, you were immersed in the world of printing and photography. How did that evolve into your own practice?

TP: Yes. You can imagine the fun I had printing those negatives. Well, that’s why I still feel today, after so many years, I still have confidence in being able to print a good negative. And I’m not happy until I produce the best I can. When I was an adult myself, my husband would be in bed calling me: “When are you coming to bed?” And I’d still be in the darkroom: like, “Oh, that is the better print.”

SS: How do you go about composing or framing your photographs?

TP: I don’t direct people much—I don’t tell them to hold their hand “here” or “there.” One Sunday afternoon, I saw a woman who was quilting and I asked her if I could photograph her. After 15 or 20 minutes, she said, “Will you let me know when you’re gonna photograph?” And I had already taken twelve images on the roll.

Usually though, I get to know someone pretty well before I would ever ask if I could photograph them, so they would be comfortable.

When I started, I could only take head-and-shoulders images. I was so wrapped up in the facial expression that it was sort of scary for me to capture what’s beyond it. But once I got to know people and got to see where they homesteaded, it was much easier for me to take larger images, to include the environment.

Thelma Pepper, Thankfulness, 1985. Silver gelatin on paper, 33.8 x 33.8 cm. Collection of the University of Saskatchewan. Gift of the artist, 1996.

Thelma Pepper, Thankfulness, 1985. Silver gelatin on paper, 33.8 x 33.8 cm. Collection of the University of Saskatchewan. Gift of the artist, 1996.

SS: There’s intimacy in that process—when you get to know the person before you photograph them—and I think it shows in your photographs. This particular show coming up at the Remai called “Ordinary Women” focuses on photographs of older women. How did you start taking those photos?

TP: The connection began through reading, actually.

I had absolutely loved reading to my four children, even when they could read themselves. We always had long reading-aloud periods. So when they left home, I needed something to do, and there was a long-term care home just two blocks from where we lived. So I went there twice a week, reading pioneer stories of Saskatchewan. But within two weeks, I wasn’t reading to them. They were just pouring out their stories to me, fascinating stories about the prairie. And I was so excited. I found the stories so historical, that before long, I had to get my tape recorder out—then photographing them, eventually.

I strongly believe that reading and being read to was key to people thinking, reflecting and knowing more about their real selves. I believe that through this process, they were identifying the things that would make them confident and happy. They loved to talk about their lives, their challenges and passions.

SS: We often think of history as something that’s big and faraway. And we forget that people that you meet everyday, ordinary people, are history too.

TP: Yes. I get what you mean. After that project with the seniors at the home, I was photographing a lot. I was 10 years photographing women, and then 10 years photographing little disappearing Saskatchewan towns.

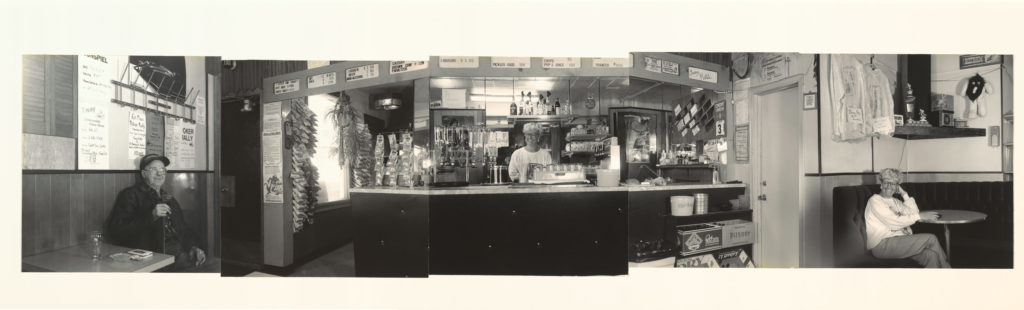

And there are different social histories I documented during those years. In one little town I found a woman who had bought a hotel and bar with her husband. At first she had said, “Oh, it’s dirty, this place, I don’t want anything to do with it.” And then, after a few years, she said, “I don’t think I would have sold this place for any amount of money.” She enjoyed meeting the people. She says, “I am supposed to know where everybody’s at and what they’re doing.”

There are other histories reflected in photos too. One of my favourite photographs is a large panorama of Fish Creek, Saskatchewan. That’s where the Métis successfully battled the Canadian forces during the 1885 North West Rebellion. Some people say that was the second most important battle in Canadian history after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Quebec City in 1759.

Thelma Pepper, Lidia’s Country Bar, Tway, 1993. Gelatin silver print, 19.2 x 86.6 cm. The Mendel Art Gallery Collection at Remai Modern. Gift of the artist, 2001.

Thelma Pepper, Lidia’s Country Bar, Tway, 1993. Gelatin silver print, 19.2 x 86.6 cm. The Mendel Art Gallery Collection at Remai Modern. Gift of the artist, 2001.

SS: Are you still taking photographs today?

TP: I still have my Rolleiflex camera that I bought on a trip back to Nova Scotia. I can’t use it much now. But the thing I still do enjoy doing, and that was a big part of my photography process, is just asking people about themselves. I am just full of questions. When people get a chance to tell their life story, or talk about significant parts of their lives, I think they come away feeling good about themselves.

SS: Telling a life story can make the teller feel differently about themselves, then—that’s something you’ve learned.

TP: Certainly there was a lot to hear from a number of the women I photographed. They were all over 85 years of age—decades of voices. Everybody has a story.

SS: And how do you feel about your upcoming Remai Modern retrospective?

TP: I guess photography, again, it’s been my medium, hasn’t it, for the history that I love. I have my own sort of joy from doing what I do and I still believe in the power of creativity. Along the way, I learned about how important it is to stick to one thing and do it well rather than go from one little thing to another. And I learned about insight and intuition.

I also just want to say it’s important that I didn’t start out to be a photographer—all these projects came as a result of reading to people. They all came out of the power of voice.

Other voices have helped me too.

In some ways I want to credit my son, who is a filmmaker. He was the one that saw something in these portraits when I started out, when I said, “I’m just having fun.” He saw something in them before I did and encouraged me to go on.

And I often think of a grandmother that I never met; she died at 32. She apparently was a beautiful reader. But since she was very Irish and Catholic, and the church near her was Protestant, she couldn’t read aloud in church; she had to read from outside. Her memory, passed down to me, reminds me of the power of voice, too.

“Thelma Pepper: Ordinary Women. A Retrospective” runs until August 15 at the Remai Modern in Saskatoon.

Thelma Pepper, Where Grace Found Freedom, 1989. Gelatin silver print, 39.3 x 109.4 cm. The Mendel Art Gallery Collection at Remai Modern. Photographers Gallery Collection. Gift of PAVED Arts, 2011.

Thelma Pepper, Where Grace Found Freedom, 1989. Gelatin silver print, 39.3 x 109.4 cm. The Mendel Art Gallery Collection at Remai Modern. Photographers Gallery Collection. Gift of PAVED Arts, 2011.