YL: The exhibition is divided into sections, there are historical photographs and contemporary photographs. Can you talk about the relationship between them?

SC: If we look at the series by Lebohang Kganye, a very successful South African photographer, what I thought was really interesting is that it has some continuity with the history of African photography. In these images, we see Kganye wearing the clothes of her deceased mother, [an image which is then digitally] juxtaposed on the original picture of her mother.

When we look at the studio photographs by Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, there are what I call the twinning images: these women coming dressed the same as the photographer to commemorate this sort of bond. You know the expression “cut from the same cloth?” It’s something that’s been traditionally done: creating and wearing a similar dress to express some kind of solidarity, or bonds of friendship or family. And what I thought was really interesting is that Kganye is following this tradition in a new way.

You have a strong connection in African photography between textile and photography. In the 19th-century room, in one of the windows, is a book with photographs by an African photographer, and you can see how [the subjects] sit with legs wide apart is so that the textile is visible. Very often the pattern on textile had meaning; it conveyed social status, among other things. What’s fascinating with photography is that for a very long time people thought it was a machine, that it was mechanic, and that it was always being used in the same mechanical way. This example of textiles in the image shows how photography has been culturally appropriated in different ways.

YL: Attention to African photography is changing. The history of African photography is largely unknown in the West. How do you think it is changing, and why? Maybe a biennale is one way, or an archive.

SC: One thing that was recently “discovered”—and I’m very carefully using this word “discover,” because in the West we consider that we’ve discovered something even when it has been there for a long time, so we could say instead that it has been popularized recently—is the life of midcentury studio-portrait photographer Felicia Abban. She’s still alive; she had her own studio in Ghana in the 1950s. And so that’s something completely new. We always assumed that there were only male practitioners in these studios, and now that’s completely shifting. We are telling the history of photography in the continent because we know now that there were female photographers practicing and having their own studios.

It’s true that the concentration of images in the exhibition are from South Africa, West Africa (Mali, Nigeria) and then East Africa, especially in the historical room. The research about African photography is still a very young discipline, it’s barely 30 years old. It’s still something we are unravelling. There is tons [more] that needs to be done. I’ve done my own research about [photographic histories] in Central Africa, and in the Congo; I was the first researcher to do that.

So there are tons of things we don’t know yet, which is exciting, but at the same time daunting. I think in the coming years we will understand more and more about how photography has been used in particular cultural ways in Africa.

![A. C. Gomes & Sons, <em>Natives [sic] Hair Dressing, Zanzibar, Tanzania</em>, late 19th century. Collodion printed-out print. Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg.](https://canadianart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/1-web-768x1087.jpg) A. C. Gomes & Sons, Natives [sic] Hair Dressing, Zanzibar, Tanzania, late 19th century. Collodion printed-out print. Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg.

A. C. Gomes & Sons, Natives [sic] Hair Dressing, Zanzibar, Tanzania, late 19th century. Collodion printed-out print. Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg.

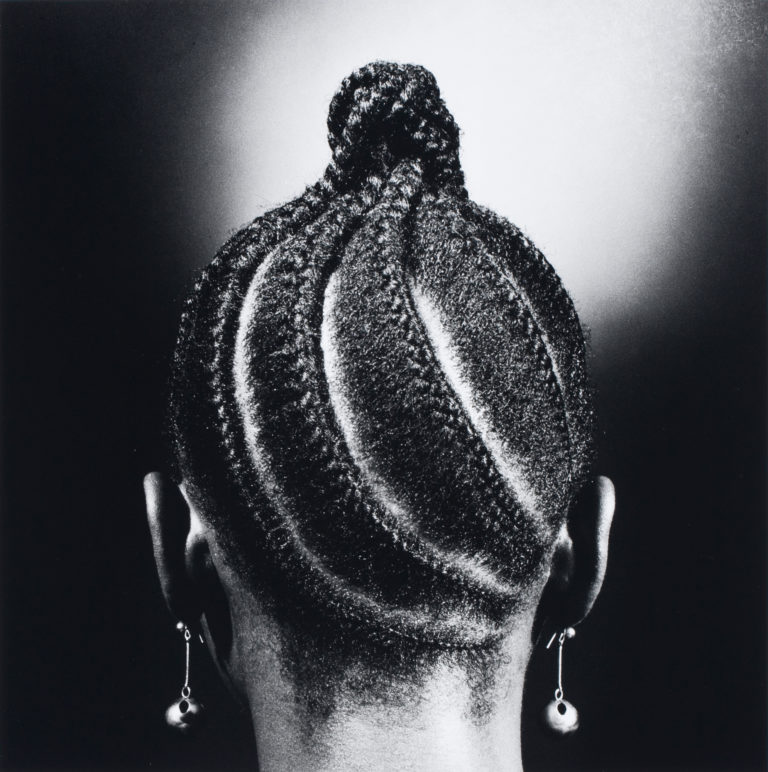

J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, Untitled (Suku Banana Onididi), from the series Hairstyles, 1974 (printed 2009). Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Galerie Magnin-A, Paris. © The artist.

J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere, Untitled (Suku Banana Onididi), from the series Hairstyles, 1974 (printed 2009). Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of The Walther Collection and Galerie Magnin-A, Paris. © The artist.