If you look at Amazon, every month there’s a book that comes out with the title Dark Matters. But for me, the title of my book Dark Matters actually came out of some of philosopher Lewis Gordon’s work, where he uses the terms “dark matter” and “white prototypicality.” I went back to thinking about how other people have theorized dark matter or blackness or space and I found that dark matter is a repository for so much of the unknown or that which we can’t put into words. I’m not a physicist or an astrophysicist, but I see how dark matter comes to be this thing that distorts and disrupts all that is around it. (There are so many spaces in which you can think about redaction as dark matter—like what happens when blackness is in the frame, or it’s just redacted entirely.) All of the kinds of things we put onto blackness, and black people, can also be thought of in the ways that we project the unknown, or what is not yet known, into the concept of dark matter as a theoretical concept for thinking through black social life. What happens when we put the conditions of blackness into how we think about surveillance or policing or carceral practices or theorizing surveillance?

In my research I do work on facial recognition technology; many of these technologies are ill-equipped to accurately recognize darker skin tones. There’s something about that unseenness, that obfuscation, that is liberatory. There’s a reason we might want to be unknown or unrecognized by a white supremacist gaze and all of its technologies. That unknowingness, that non-recognition, by certain aspects of power—heteronormativity, white supremacy, capitalism—has some productive possibilities to trouble and maybe change our current condition.

I find that some black creative practices give us a way out. James Baldwin has this short essay, “The Creative Process,” on artists and the creative process, where he writes about the idea of aloneness and being seen. He situates artists as disturbers of the peace—and this deliberate kind of disruption is the role of the artist because the role of the artist is to illuminate the darkness. In my work that illuminating is a really important strategy and method around challenging surveillance, or troubling its methodologies. There have been so many innovations by artists—whether it’s Sadie Barnette or Sable Elyse Smith or Sondra Perry or American Artist or Angela Hennessy, there are just so many I could name!—that have all been looking back, talking back and troubling and illuminating and theorizing surveillance, carceral practices, the state, the FBI or even just work life and culture and the drag that it is to always be under a repressive type of gaze and system. And so for me, I think their work has been a way to show the emancipatory possibilities of art. It’s disruptive. It disturbs. And that’s a good thing. —As told to Yaniya Lee

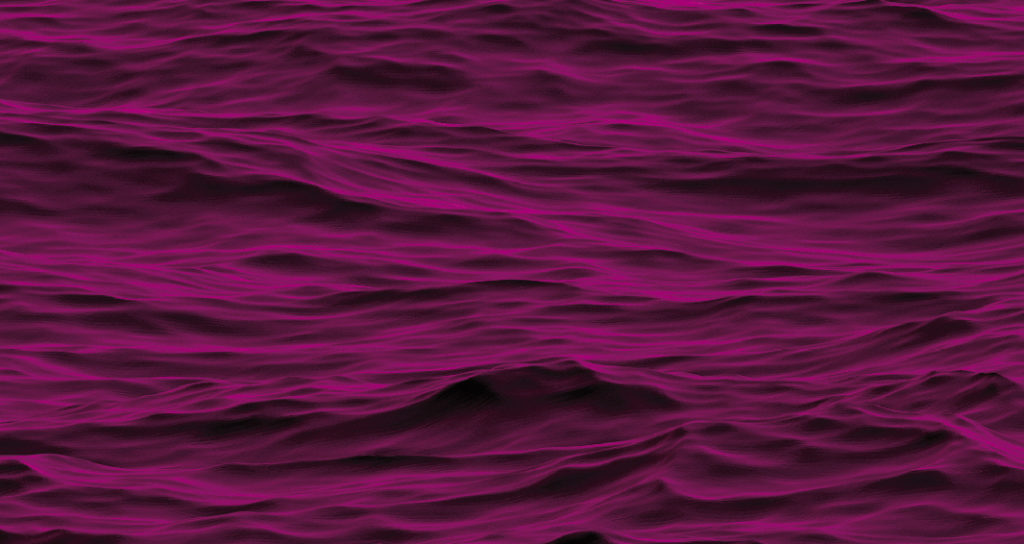

Sondra Perry, Typhoon coming on (still), 2018. Multi-channel seamless video projection with sound. Courtesy Bridget Donahue, New York. © Sondra Perry.

Sondra Perry, Typhoon coming on (still), 2018. Multi-channel seamless video projection with sound. Courtesy Bridget Donahue, New York. © Sondra Perry.