Sandra Brewster’s solo exhibition “Sandra Brewster: Blur,” at the Art Gallery of Ontario, continues her engagement with the materiality of storytelling, memory, experience and movement—themes she explores through a photo-based gel-transfer process. A massive image, Untitled (Blur) (2017–19), greets the viewer, marking the start of a personal and multisensory examination of layered selves, motion and the indelible presence of Black people within spaces that often resist their identities. Walk on by (2018), a silent Super 8 video transfer, hauntingly presents the collision of time and technologies, while Untitled (2015–16) offers a series of portraits in profile on wood panels, revealing the artist’s concern for the interior lives of her subjects. All the pieces in the exhibition mash up both the temporal and the spatial, and further Brewster’s interest in the ongoing effects of Caribbean-Canadian migration, intergenerational dialogue and the complexities that come along with laying claim to one place while feeling connected to another.

I spoke with Sandra Brewster about process, the influence of memory and the enduring legacy of presence.

NP: You’ve been creating photo-based gel transfers as part of your practice. Tell me why you’re drawn to this process.

SB: In an early series called Smiths, I created a collection of characters with Afros, drawn and painted in various visual narratives, and included them in grids on large wood panels. The faces of these characters were replaced with areas of the pages of the “Smith” section of the phone directory.

I discovered photo-based gel transfers in various paintings and was interested in collage and mixing media. Initially, I was just cutting out sections of the phone book and gluing them onto the surface, but then I started to transfer the ink to wood. I began to photograph people, enlarge them, print them, and would use gel medium to transfer their image among a grid of Smiths. While the Smiths were created to mock the notion of a monolithic Black community, the larger images of people placed over them was meant to suggest a relationship between realistic representations of people and the monolithic Smiths.

I really liked the result of these transfers. They looked worn and weathered, like posters on the side of buildings. When I started my masters program at the University of Toronto, I decided to concentrate on this process in order to further explore why I was attracted to it. This allowed me to take some time to delve into [various] interpretive possibilities [created by] the results of the transfer.

Black people have a way of holding back, keeping something to ourselves. There is power in that, in being able to conceal parts of who we are.

NP: There’s a real impact that comes out of the transfer process, which opens up a lot of interpretive directions.

SB: Yes, the transfer is about a movement from one place to another. The ink is leaving the surface of the paper and is being transferred to another surface. And because of the limited amount of control I have over the process, the paper I am working with may tear or crease. Sometimes the ink doesn’t adhere completely to the surface. This adds to the quality of the image in the end. A theme attached to my overall practice is the movement of people from the Caribbean to Toronto, and how that change of location and environment affects people’s sense of self, not only for themselves but also their children. So I see this transfer process as being similar to what happens when a person migrates from one place to another. A change occurs.

NP: You’ve titled your exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario “Sandra Brewster: Blur.” “Blur” isn’t always understood as something positive or affirming. How do you define the word in the context of this exhibition?

SB: “Blur” plays with and was inspired by all of the interpretations I mentioned: [how the works] explored movement and referenced migration and how the effects of migration may influence and inspire the formation of one’s identity here—whether the person was born elsewhere or is the child of a person born somewhere else. The intention of the blur is also to represent individuals as layered and complex: to not see people solely in one dimension; [and to be] aware that a person is made up of [both] who they are tangibly, and so many other intangible things, which includes their experiences with time and location—whether they access this on their own or through generational storytelling.

For many in my family who are of my generation or younger, we have been raised learning about Guyana through the older family members. For me specifically, I have visualized memories that are not my own; somehow I have some access to them. I think this is very interesting. This all defines a blur to me: layered, beautiful and affirming—to know that people are made up of so much more than what you see on the outside…than what is presumed. In her book Bread Out of Stone (1994), Dionne Brand wrote: “we come full of ourselves—who we were and are and will become.” This quotation resonates with me because it simply, yet with an ephemeral weight, clarifies the dimensions embodied in one person. I consider this embodiment a legitimate sense of identity.

Sandra Brewster, Untitled (detail), 2016-2018. © Sandra Brewster and Georgia Scherman Projects. Photo: AGO.

Sandra Brewster, Untitled (detail), 2016-2018. © Sandra Brewster and Georgia Scherman Projects. Photo: AGO.

NP: Themes of erasure and absence are prevalent among Black artists working in Canada. And yet in this exhibition you’ve kind of complicated that narrative by doing the obscuring yourself. You’re actually implicated in the process of blurring. How does that relate to conversations about erasure?

SB: It’s like a resistance, isn’t it? Black people have a way of holding back, keeping something to ourselves. There is power in that, in being able to conceal parts of who we are. I hope people will encounter the work and have a certain kind of relationship with it where they just know what I’m doing because they understand where I’m coming from, because they come from a similar cultural background. Like some of the artists you’re referring to, I am, in part, also bringing awareness to a rooted presence here. By obviously obscuring something, one makes it even more apparent. It’s a visual strategy.

NP: The images resist easy or casual scrutiny. The viewer has to work hard to consider them, to understand what they convey. But it seems to me that someone, depending on their own identity or lived experience or their politics, may refuse to do that work. They may have a very different experience and refuse to give the work its due. So I’m curious about the kinds of reactions people have to the work. What have you observed among the audience?

SB: I think in general people have given the work its due. I see different reactions. I see people responding to the whole theme of movement. I’ve observed children shaking their heads at the images [laughs]. There was a particular woman who told me the work reminded her of her own personal experiences of moving from Trinidad to England, and had her reflecting on the impact of that migration, how the change of environment affected her. I’m sincere in making the work. I think movement is really important. I see it as a legitimate identity whereby you are here but you’re always grappling with being connected to somewhere else.

The Blur series began while I was in Southside Chicago during the summer of 2016. While on an internship there I was asked to be in an exhibition at the Franklin, [a gallery in the backyard of the] home of artist Edra Soto. I created three Blur pieces from images I had previously taken in Toronto. During my stay in Chicago there was a constant awareness of the political climate. Black communities were feeling frustrated, ignored and dismissed. We were in the midst of taking in ongoing reports and publicized videos of the violence, the shootings of Black people by police. The Blur series, for those who saw it, expressed this feeling of being erased and ignored. This is how people have expressed the project to me.

From left: Sandra Brewster, Blur 18, 2017; Untitled, 2016-2018 © Sandra Brewster and Georgia Scherman Projects. Photo: AGO.

From left: Sandra Brewster, Blur 21, 2017; Untitled, 2015-2016. © Sandra Brewster and Georgia Scherman Projects. Photo: AGO.

NP: What is it that draws you to the materials you use? How do they relate to your interest in memory and experience?

SB: In my transfers the texture of the paper I work on becomes similar to that of old photographs. I like that relationship. I work on the walls of spaces because I am drawn to the idea of the work being everlasting. Even when it’s covered over by the institution to make way for new work, you cannot deny that it’s still there; there’s a permanence.

NP: Yes, I’m reminded of Katherine McKittrick’s work on Black geographies and their lasting impact on future generations.

SB: Yes, even when the work is being removed, after it has been sanded down then painted over, it’s still there. We may not see it, but there is lasting legacy. In all of the work, although the images are contemporary, they refer to the past through the materiality, the texture. I acknowledge that there is a past that has influenced my creative production and that my choices have been influenced by it.

I touched on this at the opening reception for “Blur.” I shared the identity of the model in the large wall transfer—Tuku Matthews, a singer, musician and performance artist, and a friend of mine. Her mother is jazz musician Salome Bey, and her father was Howard Matthews, co-founder of the restaurant Underground Railroad. Tuku’s sister, SATE, formally known as Saidah Baba Talibah, is a well-known singer here and abroad. I met Tuku and her sister in the 1990s, when they were part of the band called Blaxäm, led by Washington Savage. Shannon Maracle was also a singer in this band.

For me and for many, Blaxäm represented the texture of Toronto. Their music was a fusion of blues, soul, rock…. They were bold and driven and they certainly inspired me and influenced the way I saw the city and saw myself within it. Tuku and her sister are a continuation of their parents’ legacy, and that family means so much for many people in the city. The band, the restaurant, their mother’s music, have all left lasting impressions on communities in Toronto.

The Blur work conveys this. Wall works are interesting in that way. People are always concerned about what happens after the show closes, but hopefully their impression is lasting.

Sandra Brewster, Untitled, 2015-2016. © Sandra Brewster and Georgia Scherman Projects. Photo: AGO.

Sandra Brewster, Untitled, 2015-2016. © Sandra Brewster and Georgia Scherman Projects. Photo: AGO.

NP: I’m struck by how the work openly displays your labour. You can see it in the tears, folds and scratches. It forms a residue of the creative work. Are you becoming more interested in making your practice visible?

SB: That’s a good question, because when I walk up close to the large piece [Untitled (Blur) (2017–19)] at the AGO, I become interested in the interpretative possibilities, in magnifying those details. It makes me think about what is possible in the abstraction and texture of the work. But when I come in at a different proximity, the meanings can shift. I’m very interested in that.

NP: You started your career drawing powerful portraits in charcoal. Do people ask you when you’re going to start drawing again?

SB: I’m finding that when I’m doing these gel transfers, I’m making similar decisions that I would if I was drawing. There is this bridge between the drawing and the transfer. Maybe because the transfer is not a perfect representation of the image and neither are my drawings. It’s always more like an interpretation of what the subject is. Someone told me that she thought the transfers were drawings. I have to correct people all the time. I see the parallels. Another person who is aware of the transfer considers the works drawings, because of how they are produced. I also consider them within [the category of] printmaking.

NP: With the exception of the silent video in this exhibition, it’s not really possible to situate the images in a particular setting. There are not a lot of contextual cues around the images to know where they’re taken. This forced me to think more introspectively, almost psychologically, about the work.

SB: Right. I think this show was more about me and the people I know, more individual and less about setting. In one of the pieces, an image of myself is transferred repeatedly on five wood panels. I don’t refer to it as a self-portrait. But when I shot the initial photograph, I found it interesting because of its pensive, introspective quality, which brings in those psychological aspects that you mentioned. So it’s not about the setting, which might even be distracting to think about.

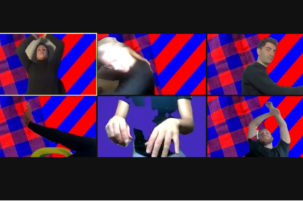

The video Walk on by is a transfer of a Super 8 film. You can tell that the subjects are contemporary figures walking through a city, but I’m hoping the impression is deeper than location. I’m thinking about the people moving through those spaces and at times blending into the landscape.