On the evening of November 6, Brendan Fernandes will premiere a new digital commission for the Art Gallery of Ontario—namely, a dance piece made via Zoom. Here, Fernandes talks about how the COVID-19 Pandemic is impacting his creative practice, and how tools like SMS and Snapchat (as well as home-office chairs) have been applied in some of his recent dance pieces.

Yaniya Lee: In this time of social distancing, what are the challenges of dancing without touching? How do you approach it?

Brendan Fernandes: I’m thinking about the protocols of social distancing—that choreography. How is that part of the rules? We always follow rules in our daily life that are choreographies—now our daily life routine has changed, so I’m taking that on as the new choreography.

Will I be making a lot of works outside? Yes, probably. Will I be making solos? Yes. Will dance for camera be part of my practice? Yes. Am I missing the live? Yes. But I will find ways.

I was thinking about this idea of safe spaces. The work at the AGO was [originally] going to debut a film called Free-Fall, which is a film that looks at Pulse Orlando, POC queer bodies and the ideas of how we’re marginalized, who protects us, who makes us visible, at what being invisible means. Sometimes I talk about invisibility as as a structure or a method or a concept.

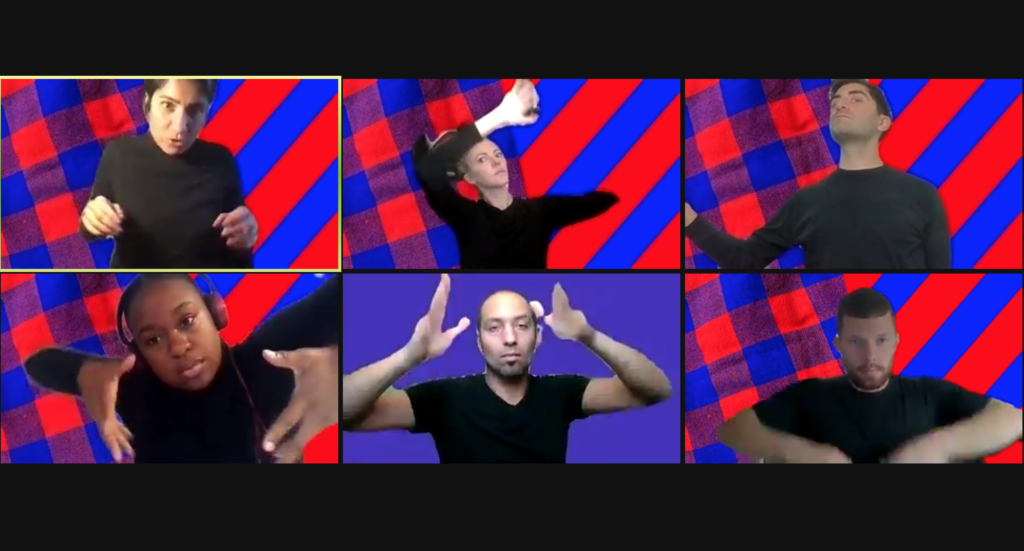

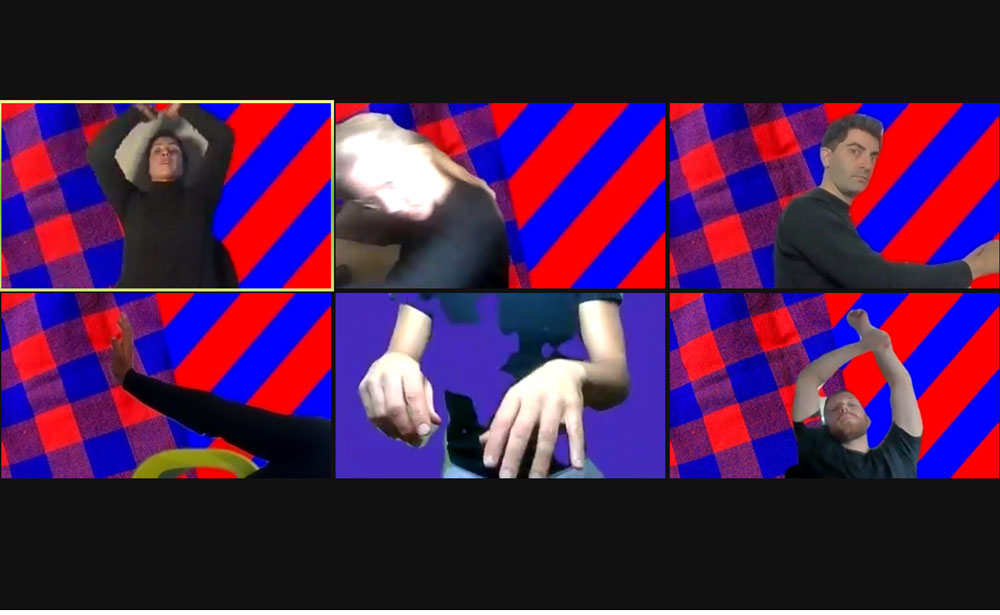

And so the piece [at the AGO] is [now] going to be based on that. Because I’m on Zoom now every day, I had this idea: let’s make a dance on Zoom. I was really curious about filters and that idea of the virtual space. I want to make a dance on Zoom thinking about safe space. The space of intimacy where I’m now here with you, but we’re also separate. It’s a safe space, a virtual space, that brings us together.

My audience is going to see something totally different. It’s going to feel a little bit like being in a club, like a moment of animation almost. There’s so many layers of space: the audience space, the virtual space that everyone’s in. And what I see is different than what you see, or what you’re experiencing—I’m really curious about that as a potential for political futures.

I have six dancers; they are all in this grid formation [on screen], and now they can move and be moments of abstraction this way. I love the idea of the grid. And we’re all dancing with these filters, so that filters bring us into the same space.

Jerome Harris, custom backdrop for Brendan Fernandes’s live Zoom performance The Left Space at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Jerome Harris, custom backdrop for Brendan Fernandes’s live Zoom performance The Left Space at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Jerome Harris, custom backdrop for Brendan Fernandes’s live Zoom performance The Left Space at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Jerome Harris, custom backdrop for Brendan Fernandes’s live Zoom performance The Left Space at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Jerome Harris, custom backdrop for Brendan Fernandes’s live Zoom performance The Left Space at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Jerome Harris, custom backdrop for Brendan Fernandes’s live Zoom performance The Left Space at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

YL: How did you arrive at the filters?

BF: The filters are based on a Maasai warrior print, which is a colonial textile. Plaid is not African, but it’s become indicative of Maasai culture. And the reason why they wear it is because the colours create this visual noise that hurts the eyes of predators, so it becomes a protective mechanism.

I have eight filters. I work with a graphic designer named Jerome Harris, who is a dear friend. I talked to him about this pattern, but also [about] dazzle camouflage, which was the way that ships were painted in World War I so you didn’t know where the ship started or ended. There’s this idea of visibility and invisibility again.

This camouflage is super in your face. So the dancers play in and out of [the filters] using the camera, turning the camera on and off, augmenting the camera. The dance all takes place [in the frame of the camera]. We’re creating this space, this collage, this grid.

YL: You’re playing with Zoom technology in your dance in an innovative way. Is there a history of dance and technology?

BF: I don’t know. When pandemic happened, I had already been thinking a lot about dance and technology. [I did] a piece called I’m Down and also [one called] A Call and Response here at the MCA in Chicago. You would subscribe to a text messaging system, and then I would send you daily texts that would create an ongoing dance score.

And then I’ve been thinking a lot about another piece I did at the MOMA called Art by Snapchat. Bruce Nauman did a piece called Art by Telephone at the MCA Chicago [in 1969]. The telephone would ring in the museum, he would pick it up and people would give him instructions on how to move. What I did was create a dance score based on Snapchat. I have a group of dancers moving throughout the museum. They’ll be dancing; they’ll be moving; they’ll be doing something and then all of a sudden, through my instruction in the form of a buzz, they all [follow an instruction in the Snapchat video].

Rehearsal screenshot for Brendan Fernandes’s live Zoom performance The Left Space at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Rehearsal screenshot for Brendan Fernandes’s live Zoom performance The Left Space at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

YL: So you have already been integrating technology into your dance for a while.

BF: Yes, in these weird analog technologies like Snapchat or texting.

In Hong Kong when the protests were happening the government shut down [information on] the Internet [about the protests] so the protesters couldn’t gather. They couldn’t come together. So what they were using was AirDrop as a way to communicate.

I was really curious about that way of gathering and organizing through AirDrops. What I do now sometimes is I’ll make a good graphic, saying “Vote” or something like that, and if I’m on the train I turn on my phone and whoever’s on AirDrop I just drop the graphic to them. That’s another way that I use technology, but it’s a minor performance. Someone gets it, someone might not accept it, but there’s this way I [can] disseminate work.

Technology and dance has been something I’m really pushing for. Right now it’s a little bit more in my means. I’m a Zoom expert now: I use technologies like Zoom to make dance. You play with the camera by covering the camera or switching the filter. And I put [the dancers] on wheelie chairs so they can pan and move. One of the biggest things right now that I’m trying to get them not to do is to look at the camera. We’re so used to the camera. And I [tell them], “I want you to give me other poses, but make sure you’re not just staring straight.”

Zoom definitely has its challenges and its glitches. Working with the dancers, I’m like: “Listen, OK, we’ve got to figure this out together.” Because dancers are perfectionists. It’s a different process of learning as well. If we try to do something in unison and the computer lags on someone else’s end, they’re a few minutes behind. All the dancers are in Toronto. I’m in Chicago. We get on these [Zoom] rehearsals and someone’s Internet is slow so it’s a little bit challenging.

We’re living right now in the most precarious times. We have to be optimistic. We have to be hopeful. Because if not, how do we move forward? And I love that idea of moving forward because that’s the language of dance.

Rehearsal screenshot for Brendan Fernandes’s live Zoom performance The Left Space at the Art Gallery of Ontario.

Rehearsal screenshot for Brendan Fernandes’s live Zoom performance The Left Space at the Art Gallery of Ontario.