In her 2006 series of photographic self-portraits Roaming Carrie Mae Weems stands in the midst of the monumental structures and landscapes of Rome, Italy. Positioning her body within and against these looming backdrops, she shows how such architectures not only exert, but reinforce power. This theme resonates throughout her longstanding practice in relation to history, to work, to family and to how we relate to one another.

The West coast native moved to New York in the 1970s, where she took a class at the Studio Museum in Harlem with Dawoud Bey and met a community of like-minded artists. Since the early 1980s, and her first monograph “Family Pictures and Stories,” Weems has expanded these same themes of power and relationality in texts, videos, installations and theatre. Her most notable works include The Kitchen Table Series (1980) and From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried (1995–96).

This year, Weems is the featured artist at the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival in Toronto and will present an exhibition in five parts: “Heave” at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto, “Blending the Blues” at the CONTACT Gallery, and the public installations “Scenes & Take,” “Anointed” and “Slow Fade to Black” across the city. Weems will also present an artist talk on Saturday, May 4, at the University of Toronto’s Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design.

Yaniya Lee: Your projects are often in conversation with and influenced by other people’s work. Do you get strength from other artists?

Carrie Mae Weems: I think that all artists are influenced by other artists, and I’m no different. I try to spend time with other artists, with their work, with their books, with their images, with their music, with their dance. And just looking. One of the lectures I’ve been giving over the last year has been on the essay of influence, thinking about the way in which artists are constantly borrowing from one another, looking at one another. In some cases it might be a Lorna Simpson work that’s based on a Duchamp piece from the 1930s, or it might be Aretha Franklin borrowing from Frank Sinatra. Or Frank Sinatra borrowing from Nina Simone! I’m interested in the way we impact one another and we influence one another. We learn from one another, and we are always in constant dialogue with the art of the past as we attempt to inscribe our own nuance and our own meaning on a project.

YL: You describe the early years of your practice, when you would go to the studio every day no matter how frustrating it was. I get the sense that you were working all the time, and still are, from the moment you wake up until you go to sleep. I’m curious to know what you do when you’re not working. Do you have a practice of repair?

Most people are interested in beautiful things that don’t necessarily cause them to think very deeply.

CMW: The reality is [that] working and teasing out this moment—these moments—that I’m alive is the most exciting thing that I do every day. Coming from my studio, working out social problems and working it through the visual, or through language or through photographs or through videos or through our concerts, I get a chance to do all the stuff—what a lucky girl!

Every once in a while, I’ll get my nails done, and occasionally—in the midst of working—I’ll try to have a dinner party. I do know how to relax, but my primary mode of operation is being in my studio working, and that brings me the greatest joy.

YL: I think it’s wonderful, that means you’re happy all the time.

CMW: Yes, even when I’m exhausted. I’ve been on tour with my performance project Past Tense for the last three or four months. This really square guy came up to me at the end of the evening the other night—Saturday night, after our last performance—and he said, “I have to say, one of the things you manage to do, which I find remarkable, is you really engage and deploy aspects of empathy, and so I am walking away from this project feeling as though the last two hours just made me a better man.”

And I thought, What a remarkable accomplishment! Some wealthy guy can come in and watch the project that’s about the history of violence and the impact of state police violence on Black men, and say “I see this. I understand this,” and “I am better person because I’ve engaged this work.” I thought, Well if I’ve done that, I’ve done my job.

YL: It seems to me that there’s an enclave within the market for Black art, and artists always have to think about this question of “authenticity.” Have you felt that imposed on you? If the art market wants Black artists to be a certain way, is there a right and a wrong way to make Black art?

CMW: I don’t make work for the market. I create out of necessity, and so in one strange way, if we were to look at how my work might be received at Sotheby’s or at Christies when it goes up to auction, there’s frankly very little interest in my work. It has been historically undervalued. I think that most people are interested in beautiful things that don’t necessarily cause them to think very deeply about any one thing. And since my work hasn’t really fit within those parameters, it’s not received well within the marketplace. That market is what it is: they’re looking for whatever they’re looking for and I don’t quite fit into the model. But I’ve grown to accept that.

Carrie Mae Weems, Heave: Part I – A Case Study (A Quiet Place), installation view at Cornell University, Fall 2018. Courtesy the artist/Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Carrie Mae Weems, Heave: Part I – A Case Study (A Quiet Place), installation view at Cornell University, Fall 2018. Courtesy the artist/Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

If you look at auction records, they tell a great story about what’s important to contemporary museums.

YL: You’ve talked about how The Kitchen Table Series you made in 1990 was before its time, that critics didn’t quite know how or have the discourse to address that work when it came out. What is the importance of contextualizing and historicizing works of art?

CMW: Often artists are really ahead of the curve. I have said for a very long time that if institutions wanted to be relevant to the future, then they would need to have a broader representation of artists within their collections. But for the most part, that wasn’t what museums were thinking about. They were thinking about their donors, their funders—you know, the “traditional.”

I made the Museums series, for instance, in 2006. It’s only now that people are even interested in that work and starting to request it. We’re grappling with really complicated and deep and complex issues, and it takes a while for the general public to catch up.

There is a disconnect between what I think is so significant about what Black artists are doing and where the critics are contemporarily. They’re definitely behind as the artists continue to push for new ideas. For instance, there hasn’t been a great deal of discussion around African American artistic practice, or Black practice, in relation to notions of modernism. Art critics and art historians have been slow to understand the expansion and the innovation that has happened in the field, because [those artists] have been thought of only as “Black people dealing with struggle.”

One of the things I’ve always thought would be important is that there be a young group of art historians, critics and writers about the arts who would be able to assist in situating the work critically. They’re not necessarily speaking to the artists, they’re speaking to the market, and they’re speaking to the general public. And that’s really their role, to the extent that if they’re behind, then everybody else is behind.

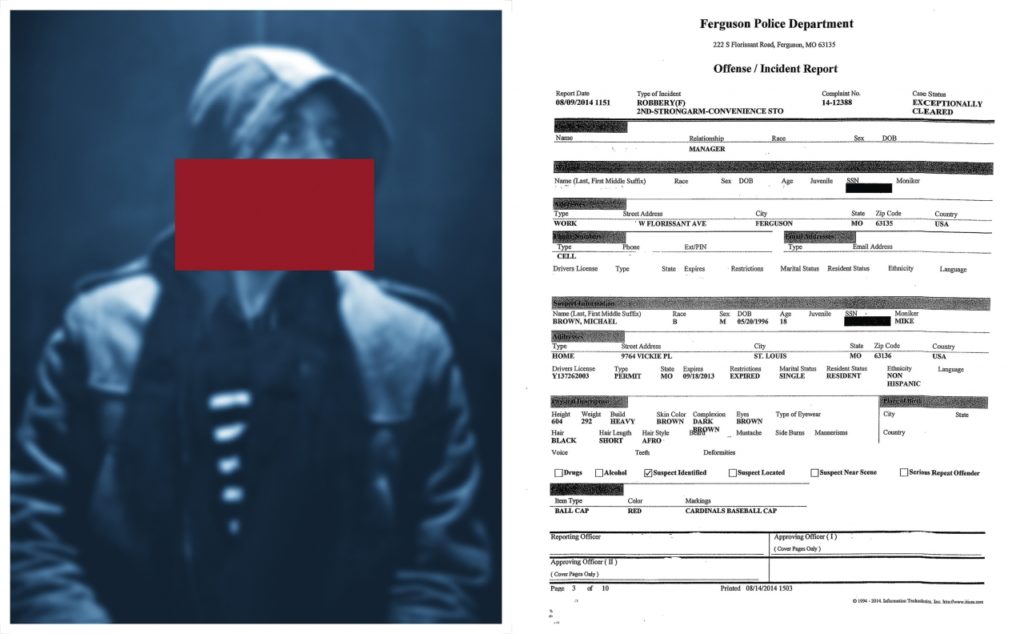

Carrie Mae Weems, All the Boys (Blocked 3), 2016. Courtesy the artist/Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Carrie Mae Weems, All the Boys (Blocked 3), 2016. Courtesy the artist/Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

YL: What you’re saying makes me think of Sylvia Wynter or Fred Moten, and all of these people doing that work in Black Studies. Even within the academy, this critical research still hasn’t totally reached art history departments yet, let alone the museum. There’s such a resistance to the idea of trying to think about modernity and blackness.

CMW: Well, you know, we exist on the edge of that. We’re not centred, and we have not been central to academic thinking. So a young person comes along and they’re made to believe that they need to do yet one more dissertation on Monet, one more dissertation on Picasso, or one more dissertation on Duchamp. But not, apparently, on Kehinde Wiley, not necessarily on Kara Walker and not necessarily on LaToya Ruby Frazier. And so to that extent the work has not really been theorized properly. It hasn’t been engaged properly. It’s still situated on the margin.

Some of us make brilliant work that’s truly inventive, and it moves not just Black society forward, but [also] the societies in which we live.

If you look at auction records, they tell a great story—a great narrative—about what’s important to contemporary museums. And that is still, for the most part, white men and what they do, because they command the greatest value. Most museums represent white people; they don’t necessarily represent brown people. They don’t represent the breadth of the society in which they’re situated. But the gig is up, and many of [those museums] interested in maintaining a kind of relevance to contemporary society are now thinking, “Oh, wow, we are behind, and how do we catch up?” So it’s an interesting, dynamic time.

YL: Yes, I think it’s really exciting. But I am wary about how they try to catch up. There’s this very short-sighted will to overcorrect, and that means they’re just grabbing anybody who looks the profile, and it’s dangerous.

CMW: That’s right. I completely understand that.

YL: You have travelled extensively and, I’m sure, encountered different Black diasporas in their own political and historical contexts. You grew up Black American, which is such a monolithic culture and influences perceptions of Black cultures all over the world, but yet it’s still different than these special localized contexts of blackness.

CMW: Every place you go in the world, Black people have been thought of in very particular derogatory ways, and we’ve been stereotyped in very specific ways. Always, of course, as “less than.” Whether you are in Africa or the United States or Canada or Latin America, it’s the same. That impulse to denigrate blackness and the Black body is universal. And our response to that denigration has also been universal. Who are we in these countries? These colonial empires brought us here only as servants to their needs, yet what we managed to build out of that has been remarkable.

Carrie Mae Weems, Slow Fade to Black (Dinah Washington), 2010. Courtesy the artist/Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Carrie Mae Weems, Slow Fade to Black (Dinah Washington), 2010. Courtesy the artist/Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

One of the things I started to realize is that historically, when people have been squeezed, when they’ve been seriously squeezed with the assumption that you could destroy them, what comes out of that threat of destruction has been an extraordinary level of creativity in the act of living. Some of the most important music made in the world has come out of this pressure of survival. It is, in other words, that brilliance of the act of living when somebody is attempting to destroy you, that we find a way and a means to articulate the breadth of our humanity regardless of the forces that are pressing on us. It’s remarkable that even as we search for our identity [we are able] to gift and to bring forth something that is truly innovative.

And then you think about people like Fred Moten and Claudia Rankine using the master’s language to subvert the master in brilliant ways, [it’s] almost unprecedented. So we continue and we make great work and important work and vital work. And some of us make brilliant work that’s truly inventive, and it moves not just Black society forward, but [also] the societies in which we live.

Carrie Mae Weems, Anointed, 2017. Courtesy the artist/Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Carrie Mae Weems, Anointed, 2017. Courtesy the artist/Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.