Access-to-information requests aren’t usually in the typical materials list for an artist. But they are for Montreal sculptor Sheena Hoszko.

That’s because Hoszko likes to investigate and (to a certain extent) reconstruct spaces that most Canadians never get to see—namely, the insides and outsides of Canada’s prisons and detention centres.

For her ongoing series 35 Prisons in Quebec, Hoszko is taking graphite rubbings of the ground around all of the federal and provincial prisons in Quebec. Last year, for her Central East Correctional Centre piece at Peterborough’s Artspace, Hoszko amassed security fencing equal to the perimeter of a nearby Canadian Border Services Agency detention centre, stacking the fencing in the gallery so it made two large masses. In 2015, Hoszko used drywall to rebuild a Laval prison’s segregation unit at Axené07 in Gatineau.

And right now in Calgary, at the New Gallery, Hoszko is using rented drape and pipe to reconstruct the minimum spatial requirements for mental healthcare waiting rooms and treatment rooms in Canadian prisons. It’s based on information she has gleaned from Correctional Service Canada’s Federal Correctional Facilities Accommodation Guidelines, a 700-page document she received via an access-to-information request.

Hoszko’s ultimate goal with all this artwork? To prompt viewers to consider what it might be like to abolish all prisons. Here, in an edited phone interview, Hosko talks about the origins of her work, its connections to science fiction, the activist organizations she admires and more.

Sheena Hoszko, Toronto Immigration Holding Centre (total perimeter: 1164 feet), 2015. Rented security fencing and postcard writing station. Perimeter of the Canada Border Services Agency detention centre in Toronto. Measurements obtained by walking the perimeter. Installed at Toronto’s A Space Gallery. Image courtesy the artist.

Sheena Hoszko, Toronto Immigration Holding Centre (total perimeter: 1164 feet), 2015. Rented security fencing and postcard writing station. Perimeter of the Canada Border Services Agency detention centre in Toronto. Measurements obtained by walking the perimeter. Installed at Toronto’s A Space Gallery. Image courtesy the artist.

Leah Sandals: What drives your interest in prisons and other spaces of incarceration?

Sheena Hoszko: There is an interest from a personal perspective—there are people in my family who have experienced some incarceration, and also people in my family who participate in the spaces of incarceration. So that is something that has always been present in my life.

As a sculptor, I work with space, and prison and incarceration is almost the endpoint of power and space. So I think, as a sculptor, that is my investment in it.

And then, from an organizing perspective, I see incarceration, specifically in Canada, as an underrepresented issue.

I’m a white, female-bodied artist, and I do have a lot of mobility, and I do have a lot of privilege—and I think it’s important for me to highlight things that I think are underrepresented in an art context.

So I have worked around themes of incarceration for a while, and I plan to keep doing on doing that.

Sheena Hoszko, Segregation Unit 01, 2015. Drywall, wood, paint, dimensions of a solitary confinement unit in Laval, Quebec, based on word-of-mouth testimonial. Accompanied by info flyer about solitary confinement in Quebec. Installed at Axeneo7, Gatineau. Image courtesy the artist.

Sheena Hoszko, Segregation Unit 01, 2015. Drywall, wood, paint, dimensions of a solitary confinement unit in Laval, Quebec, based on word-of-mouth testimonial. Accompanied by info flyer about solitary confinement in Quebec. Installed at Axeneo7, Gatineau. Image courtesy the artist.

LS: In a recent article you wrote for MICE magazine about the late prisoner-artist Peter Collins, you observed that art made by prisoners is not nearly as widely exhibited as art about prisons that is made by people who have never experienced prison. Why do you think this is? What needs to happen to change that?

SH: I think a lot of the things I think about in terms of incarceration and representation of the folks who are on the inside, currently, is just how there is extremely limited representation. Like, full stop.

Especially in the Canadian context—be it in media, be it in writing, be it in the arts—there are just restrictions as to how that information circulates.

I think there is also an overarching tendency, when folks are on the inside, to devalue their perspectives. There is an unwillingness to hear people and where they are at. I also see it as a lack of care for the folks on the inside.

That doesn’t mean there aren’t ways to see the multitude of work coming out of prisons. But that work doesn’t participate same art economy—and I think that, for me, it’s important to try and make spaces for people to see that work.

Sheena Hoszko, Central East Correctional Centre, 2016. Rented security fencing, letter writing and postcard writing station. Fencing equals perimeter of the Canadian Border Services Agency detention centre in Lindsay, Ontario. Includes printed testimonial and drawings from those detained inside sent specifically to be seen in the gallery. Installed at Peterborough’s Artspace Gallery. Image courtesy the artist.

Sheena Hoszko, Central East Correctional Centre, 2016. Rented security fencing, letter writing and postcard writing station. Fencing equals perimeter of the Canadian Border Services Agency detention centre in Lindsay, Ontario. Includes printed testimonial and drawings from those detained inside sent specifically to be seen in the gallery. Installed at Peterborough’s Artspace Gallery. Image courtesy the artist.

LS: Your show at Artspace in Peterborough last year did include text-works written by some of the people imprisoned at a Canada Border Services Agency facility less than an hour’s drive away. Is that one way you are trying to continue to put prisoner perspectives into a wider public awareness? By integrating prisoner-made artworks into into your exhibitions?

SH: That was the first time I did that, and I actually I think that particular project went well—but I’m very hesitant now to make work that includes voices from the inside that, at the end of the day, is ultimately under my name.

So I actually won’t be doing that again. I think the people who did it really enjoyed it, but I was uncomfortable with the ethics of that.

And I think I would like to put my energy towards amplifying first-person voices in a different way. Taking a step back, I can do that work not under the header of “an artist,” but through collective organizing.

Collective organizing is a big part of my life, too; I like the anonymity of it, and I think the anonymity is really important and key to its success—as opposed to that of an art practice.

I’m very critical of relational aesthetics or artwork as social practice. I see my art practice as sculpture. And then, from an organizing perspective, I would rather help amplify peoples’ voices on their own terms.

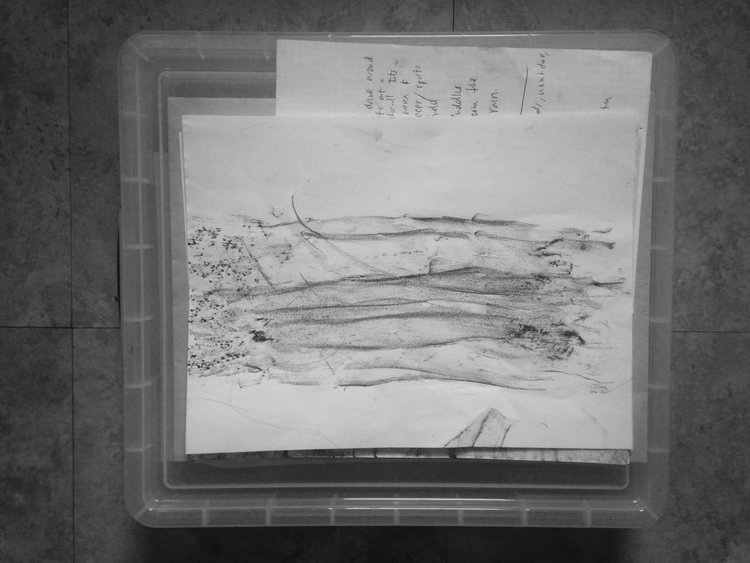

Sheena Hoszko, 35 Prisons in Quebec, 2016–2017 (work in progress). Visiting, documenting & archiving all 35 federal & provincial prisons in Quebec via ground rubbings. Image courtesy the artist.

Sheena Hoszko, 35 Prisons in Quebec, 2016–2017 (work in progress). Visiting, documenting & archiving all 35 federal & provincial prisons in Quebec via ground rubbings. Image courtesy the artist.

LS: So what do you mean by collective organizing? And how can it amplify those first-person prisoner voices to the public?

SH: There are a number of groups out there doing work that I admire.

Regarding groups in Canada, Demand Prisons Change is a letter outlining issues facing lifers on the inside. The Prisoner Correspondence Project is a solidarity project for queer people, and they have an amazing newsletter with art.

Everyday Abolition is a rad site to learn about more about those doing prison abolition work. End Immigration Detention works to end CBSA holds. And PASAN works with health as it relates to folks who are currently incarcerated.

Tings Chak and Sheena Hoszko, Artesia – Lines, 2016. Snap line chalk, graphite, tempera paint. Site specific installation linking spaces of detention in the Southwest USA to MARFA Texas. Installed at the Santa Fe Art Institute.

Tings Chak and Sheena Hoszko, Artesia – Lines, 2016. Snap line chalk, graphite, tempera paint. Site specific installation linking spaces of detention in the Southwest USA to MARFA Texas. Installed at the Santa Fe Art Institute.

LS: In a text related to your Calgary show, writer and curator Nasrin Himada writes that one can understand occupation and colonization as design projects. What have you gleaned from this understanding?

SH: I fully agree with Nasrin’s point in the text she wrote. The incarceration stats are quite shocking for Indigenous people and people of colour in Canada.

I was reading a stat here that there are 216 prisons in Canada as of 2013, and there are more than 40,000 people on the inside—while the official capacity is 38,700.

So there’s an irony: there are so many prison spaces in Canada, but they are actually so unseen. And also so hard to find: they are often hidden in the landscape; they are not on GPS; they are outside of city centres, making it really hard for family to visit .

And in terms of occupation and colonization, it is something that is kind of hiding in plain sight. Especially with the overrepresentation of Indigenous and black people on the inside.

There is a good film out right now called The Prison in 12 Landscapes. It is about the US system, but it looks at all the ways the prison exists outside the prison walls, something I’m thinking about a lot these days, too. Because the physical prison itself is almost a starting point. Then you have the police state, you have poverty, you have systemic racism—and all that is an extension of the prison system.

There’s a quote from Angela Davis’s book Are Prisons Obsolete? that I think about a lot:

“The prison…functions ideologically as an abstract site into which undesirables are deposited, relieving us of the responsibility of thinking about the real issues afflicting those communities from which prisoners are drawn in such disproportionate numbers. This is the ideological work that the prison performs—it relieves us of the responsibility of seriously engaging with the problems of our society, especially those produced by racism and, increasingly, global capitalism.”

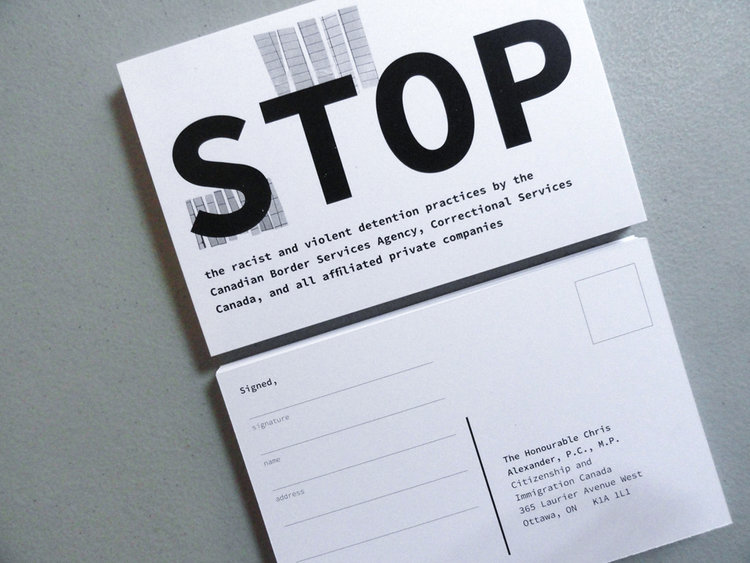

Sheena Hoszko, postcard for Toronto Immigration Holding Centre (total perimeter: 1164 feet), 2015. Fencing installation of perimeter of the Canadian Border Services Agency detention centre in Toronto. Measurements obtained by walking the perimeter. Installed at Toronto’s A Space Gallery. Image courtesy the artist.

Sheena Hoszko, postcard for Toronto Immigration Holding Centre (total perimeter: 1164 feet), 2015. Fencing installation of perimeter of the Canadian Border Services Agency detention centre in Toronto. Measurements obtained by walking the perimeter. Installed at Toronto’s A Space Gallery. Image courtesy the artist.

LS: Given that you identify as a prison abolitionist, you must get the question—a lot—of how prison abolition can actually happen. But, on what might be a related note, your website bio states you are an avid sci-fi fan. How do you think this sci-fi interest plays into your art and activism work, if at all? Are all these endeavours joined in terms of being able to imagine different futures?

SH: “Being able to imagine different futures.” Exactly.

I went to a talk recently by Walidah Imarisha, and one thing that came out of it is that a lot of political organizing can be thought of as imagining another world—aka, as sci-fi.

Prison abolition is a big statement, and I feel the big question people ask is, “What’s the Plan B?”

I guess, for me, it’s a question of imagination. If we don’t even stop to ask, “Is an alternative possible? And what would that look like?” then we are kind of doomed from the get-go.

I think it is good to work in a space of questioning and a space of imagination. To me, prison abolition is an imaginary space, but it is an important space to hold.

Sheena Hoszko, Centre de prévention de l’immigration de Laval / Laval Immigration Holding Centre (Périmètre total: 572 pieds / total perimeter: 572 feet), 2014. Rented security fencing equivalent to the perimeter of the Canadian Border Services Agency detention centre in Laval. Distance obtained by walking the perimeter of the prison. Installation view at Montreal’s Centre Clark. Image courtesy the artist.

Sheena Hoszko, Centre de prévention de l’immigration de Laval / Laval Immigration Holding Centre (Périmètre total: 572 pieds / total perimeter: 572 feet), 2014. Rented security fencing equivalent to the perimeter of the Canadian Border Services Agency detention centre in Laval. Distance obtained by walking the perimeter of the prison. Installation view at Montreal’s Centre Clark. Image courtesy the artist.

LS: Who are your favourite sci-fi authors? What are your favourite sci-fi books?

SH: The book Walidah Imarisha has edited is called Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements. I think, for me, that’s a pretty important touchstone.

I find reading these types of things is a way for me to root my thinking outside of the destructiveness of a newsfeed. At the moment, I’m finding solace and motivation from this amazing reading list.

LS: Is there anything else you want people who are looking at your art to know about?

SH: I work in a way that is very post-minimal, clean, cold and tidy-looking in a gallery space. But I do see it as a starting point for different conversations.

It’s kind of a hyperlink, where when they walk into the space, they are motivated to participate in larger social movements, or the anti-prison movement.

In terms of my own ethics of practice, in making work, the two words that keep coming up more and more are solidarity and care. Like, how do you make work in solidarity with your own movements, and movements you are not a part of? And how do we act in a caring way with each other?

At the end of the day I see my practice as a starting point for people to learn more about incarceration in “Canada,” and align myself with the many, many, many people doing this type of solidarity and care work.

Sheena Hoszko’s Correctional Service Canada Accommodation Guidelines: Mental Healthcare Facility will be on exhibit at the New Gallery in Calgary until February 18.

A view of Sheena Hozsko's installation Correctional Service Canada Accommodation Guidelines: Mental Healthcare Facility 10m2 x 2 at the New Gallery in Calgary. The installation, constructed out of rented pipe and drape, is based on prison-design guidelines Hoszko obtained via an access to information request. Image courtesy the artist.

A view of Sheena Hozsko's installation Correctional Service Canada Accommodation Guidelines: Mental Healthcare Facility 10m2 x 2 at the New Gallery in Calgary. The installation, constructed out of rented pipe and drape, is based on prison-design guidelines Hoszko obtained via an access to information request. Image courtesy the artist.